The number of children flagged via genetic tests as having an elevated likelihood of autism, schizophrenia or other neurodevelopmental conditions has exploded in the past two decades.

To better understand and serve these children, Jacob Vorstman, professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, and his colleagues at the Hospital for Sick Children opened a special clinic in 2018 called DAGSY, for the “Developmental Assessment of Genetically Susceptible Youth.” They provide the children with an integrated assessment that combines psychiatry, psychology, genetic counseling and behavioral testing, along with recommendations for treatments.

Of the 159 children Vorstman and his colleagues assessed in the clinic’s first four years, nearly 76 percent received at least one new diagnosis. About 25 percent did not have a previous diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental condition. This figure has increased from 15.3 percent in 2018 to 31.5 percent in 2021. The findings were published last month in the Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders.

The Transmitter spoke with Vorstman about his DAGSY experiences and the potential for improving both care and research for this growing population.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: What was the motivation for starting the clinic?

Jacob Vorstman: Doctors who treat newborns are increasingly using genetic testing as a standard diagnostic procedure. And a proportion of these children are diagnosed with a variant that not only caused another issue, but that also tells us that the child may develop autism or intellectual disability or another neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorder.

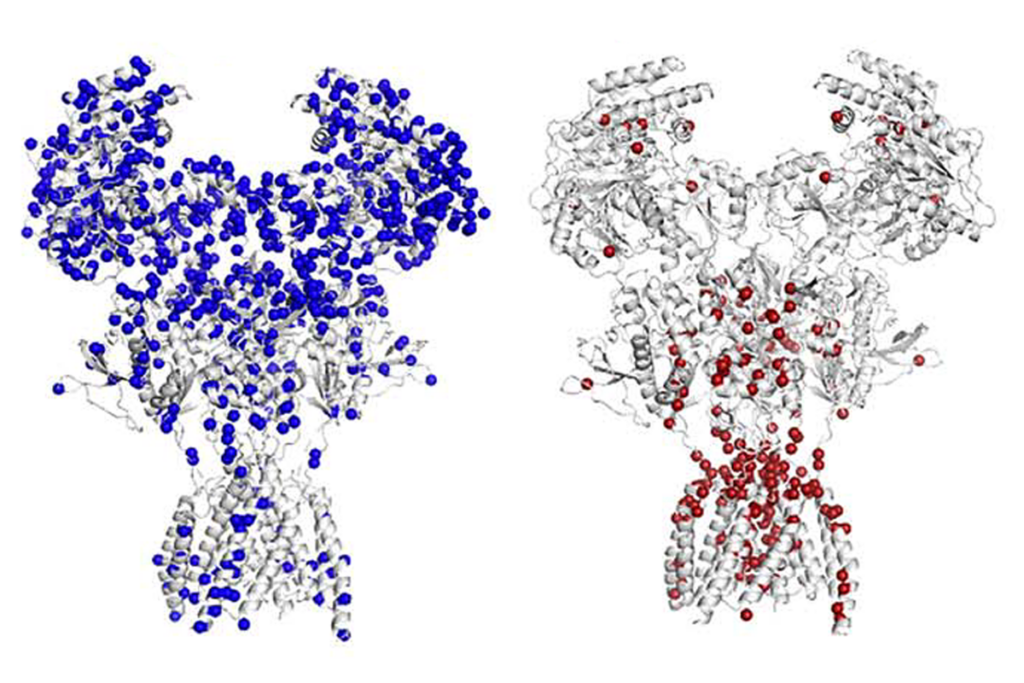

For example, previously I’ve worked on 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, and about one in four children with this variant develop schizophrenia. The genetic diagnosis is often made earlier because of another issue, but once the 22q deletion is found, from that moment onward, parents know that their child has this risk.

Or, another example, parents are told that a variant that explains their child’s health issue also predicts a 40 percent risk of developing autism. All these parents are sent home, and they have no clue what to do. Should you raise this child differently? Should we start early intervention? Should we just ignore it?

We started this clinic because we thought these parents need a place where they can come. We assess the child and give recommendations. It’s not a solution, but the parents are happy because their concerns are being taken seriously.

TT: Based on genetic screening, children can be flagged very early, but the average age of children referred to your clinic over the first four years was about 10 years. Why is that?

JV: The referring clinician needs time to learn that they can make a referral already at 12 months of age. And if you think about it, it’s not so strange, because there’s no child psychiatrist that ever has said, “OK, send me a child at 12 months.” So I have to tell the referring physicians again and again, “It’s OK, you don’t have to wait; as soon as you have the genetic diagnosis you can refer them.”

As we look at that data since 2018, we’re seeing that, little by little, the age goes down. Now regularly we’re seeing babies getting referrals at 24 months old. We’re moving to 20 months, 18 months, 12 months. The last referral before my summer break was an 8-month-old baby, although we won’t be able to do an assessment until they’re 12 months old.

TT: Can you talk about the fact that most children you saw got a new diagnosis, and many got a different diagnosis from what they had coming in? Is it because of your approach?

JV: Before the child comes in, the genetic counselor reads up on the genetic variant, and the psychologist or psychiatrist explains the risks associated with that variant to the parents. Then the parents and the child spend the better part of an entire day with us.

We use gold-standard autism assessments, we collect information on their cognitive profile and academic profile, and we do a systematic child psychiatric interview. We interview the parents as well. When they go home, we take a couple of weeks to talk to the school or the daycare, and then we integrate all of that information and create a report. It’s the first time that parents get a report like that, that actually ties the genetic diagnosis to the behavioral phenotype.

Integrating the cognitive and the behavioral profiles is super important because it helps you to be a better diagnostician. That’s why sometimes we take away diagnoses. For autism, for example, we look at the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised, (ADIR) to make our observations, but we always place the child’s social and communicative skills in the context of their cognitive abilities. So if a 10-year-old child has some social issues and communicative issues, but the mental age of that child is, let’s say, 3, then sometimes we say, well, this is not autism. The child has social communicative abilities that are as expected for a 3-year-old.

TT: Could you talk about the opportunities for research in a clinic like this?

JV: You are looking at a population that is identified by genetic diagnosis, and as a group, they have a certain likelihood of developing autism or intellectual disability. Because you’re seeing some of these children before they have symptoms, you have the opportunity to examine the trajectory from genetic vulnerability to the emergence of symptoms to the manifestation of the full phenotype.

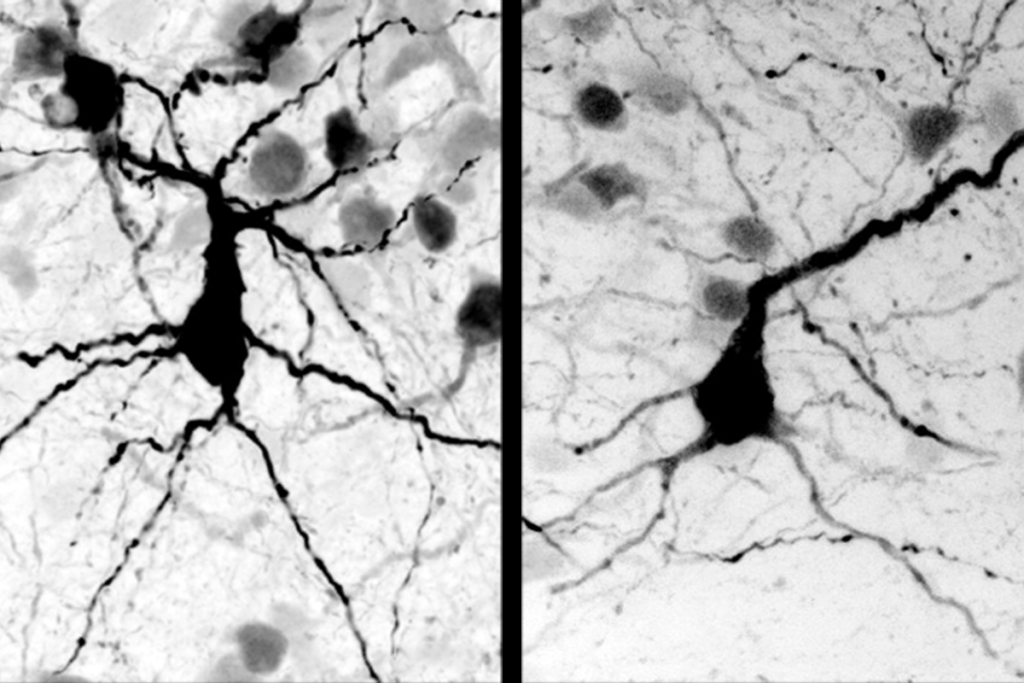

You can look for brain markers because a proportion of the kids that we follow up with will have developed autism, but for some that will not happen, so what is the difference in the signal? You can use magnetoencephalography, MRI and eye tracking, or you could use simple, traditional observation methods. We are asking for funding to look for such biomarkers.

The second topic you can study is early intervention. There is converging evidence that early intervention for autism helps, and it has positive effects on the course of the symptoms, and that the earlier you start, the larger the effect. Well, here’s an opportunity. We can actually start very early and see if the interventions are working.

And that’s super important for parents, because when they hear their child has a genetic diagnosis and the uncertainty of developing autism, it disempowers them. They’re like, “OK, it’s genetics, there’s nothing we can do, right?” So to give them some control or influence on the outcome with an early intervention would be fabulous.

TT: How easy would it be for other institutions to start their own DAGSY clinic?

JV: What characterizes the DAGSY clinic is that it’s an integrated service, so you have to have an outpatient service where there is psychology, psychiatry and genetics integrated. So that makes it expensive, right? On the other hand, it’s also efficient, because at one visit, people get the value of three visits.

For each clinic it may be different, depending on how insurance companies work, but that’s where I would start: Work together with three services and see if you can see the patient together. I started with research funding. Now other groups in the United States and Europe have approached me and want to take up the DAGSY model. If people are interested, they can certainly reach out to me and chat.