Why the 21st Century Cures Act could be disastrous for medicine

A new bill threatens to lower the scientific standards that have made the Food and Drug Administration’s approval the gold standard worldwide.

Why would anyone vote against “cures,” especially “21st century cures?” That question is the key to understanding how the U.S. House of Representatives, whose members usually can’t agree on anything, overwhelmingly passed a 996-page health bill yesterday — just a few days after the bill, the 21st Century Cures Act, was written behind closed doors.

Here’s why many health policy and consumer advocacy groups — including the National Center for Health Research, where I work — strongly oppose the bill and are asking senators not to pass the bill next week: On the bright side, the bill promises more than $6 billion dollars over the next few years for medical research and to fight the opioid epidemic. On the other hand, the ‘promise’ of that money does not include anything resembling a guarantee that the money will be provided for that purpose.

If the bill passes, those 996 pages of mostly unintelligible legislative language will influence important issues that affect all of us. Most importantly, the bill instructs the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help drug and device companies get their products on the market more quickly. Unfortunately, it does that by loosening and lowering the very scientific standards that have made FDA approval the gold standard for countries around the world.

A perfect storm of lobbying:

More than 1,450 lobbyists pushed to get this bill passed, including many patient groups and others funded by the companies that make prescription drugs and medical devices. Universities and medical schools also lobbied for the bill because they want more funding for medical research.

But physician groups concerned about patient safety, such as the National Physicians Alliance, the American Medical Women’s Association and the American Medical Student Association, oppose the bill. Dozens of nonprofit groups such as the Consumer Reports Safe Patient Project and National Consumers League also strongly oppose the bill. In one surprising twist, some of the same HIV/AIDS activists who have criticized the FDA in years past for being too rigid are lobbying against the bill because it doesn’t do enough to make sure new treatments are safe and effective.

None of these groups oppose all aspects of the bill. They just want Congress to take the time to fix it. That would mean waiting until next year instead of rushing through a bill that nobody has time to read.

The FDA’s job is to review new medical products to make sure they are safe and effective. ‘Safe’ doesn’t offer a 100 percent guarantee: Any treatment can harm some people; if the benefits are substantial enough, the FDA may even approve a treatment that can be lethal.

But on balance, the treatment’s benefits must outweigh the risks for most people. The company that makes a treatment provides all of the studies and information about it to the FDA, and scientists there review that information. For prescription drugs, that review usually entails the FDA scientists scrutinizing data from clinical trials that compare people taking the new drug with those taking a placebo or a different treatment, such as behavioral therapy.

Lower standards:

Traditionally, the goal of clinical trials is to see if a treatment improves the outcome for the participants. Depending on the condition being treated, better can mean living longer (for cancer, for example) or losing a few pounds (for a weight-loss drug) or being more able to enjoy life (for many psychotropic drugs and devices).

However, the new bill wants the FDA to make it easier for companies to prove a ‘benefit,’ by relying on ‘surrogate markers’ of effectiveness. Surrogate markers don’t measure benefits directly, but rather a secondary trait that is believed to predict the benefits. For diabetes, for example, blood glucose level is the surrogate endpoint, but the treatment’s goal is to avoid amputation or extend life. Better glucose levels don’t always predict those health outcomes.

Cancer drugs are a perfect example. Last December, researchers reported that the FDA approved 36 of 54 new cancer drugs more quickly by basing approval on surrogate markers such as tumor shrinkage, rather than on survival benefit1. Years after approval, only 5 of the 36 drugs had been proven to help people live longer, 18 definitely did not, and the manufacturers of the other 13 had not made the results of their studies publicly available (a sign that the drugs probably don’t work).

Our center looked at those same 18 ineffective cancer drugs and found that only 1 improves quality of life, 15 have no proven impact on quality of life and 2 makes quality of life worse. The most expensive of these drugs, costing $170,000 per person, is one of these last two.

Spiraling costs:

The standards for medical devices, including implants and devices that send electromagnetic pulses to the brain, are even lower than for cancer drugs. Device companies are rarely required to conduct clinical trials to prove their product is safe or effective. More than 90 percent of the time, all they need to do is explain to the FDA that their device is similar to another device already on the market.

Even when device studies are required, the companies rarely use a placebo group as a comparison to the new device. Wishful thinking can make almost any new treatment seem effective at first. That’s why so many people pay so much for treatments that don’t seem to do any good at all.

The new bill would make that situation worse, by pressuring the FDA to make it even easier for new, unproven treatments to be sold in the United States. People might end up paying billions of dollars for a wide range of treatments that were approved based on shorter studies of fewer participants and surrogate endpoints. That would increase the already-spiraling cost of insurance coverage and challenge the financial stability of Medicaid and Medicare even more than is the case today.

Don’t be distracted by the false promises of funds for medical research. The reality is that there is too much in this bill that would dismantle the structures that help physicians make informed decisions and keep us all safe.

Diana Zuckerman is president of the National Center for Health Research, a nonprofit think tank based in Washington, D.C.

References:

- Kim C. and V. Prasad JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 1992-1994 (2015) PubMed

Recommended reading

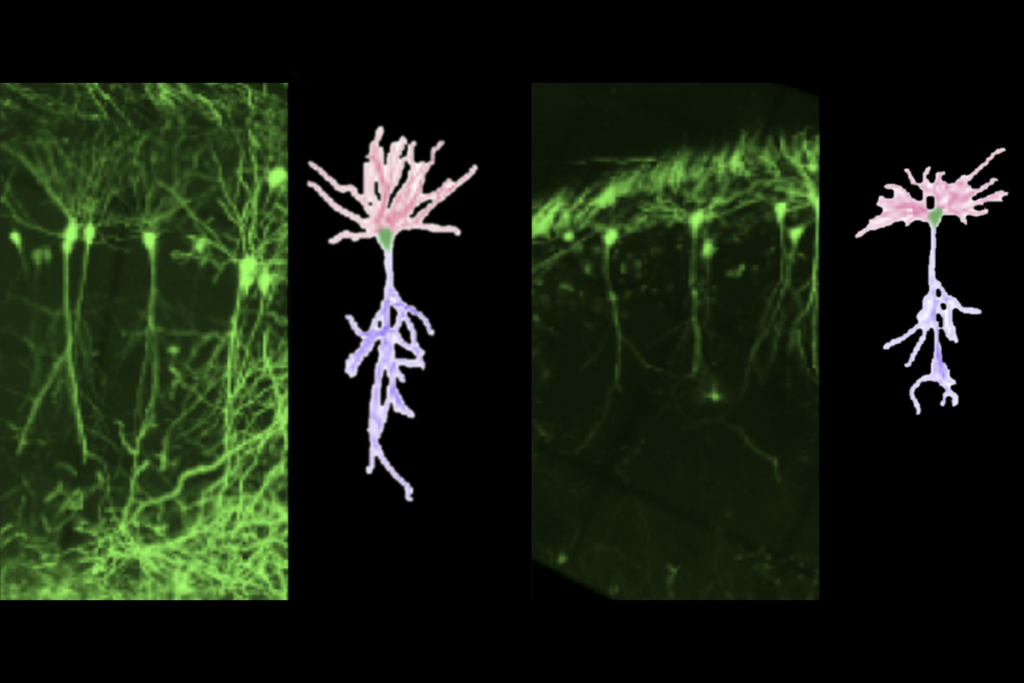

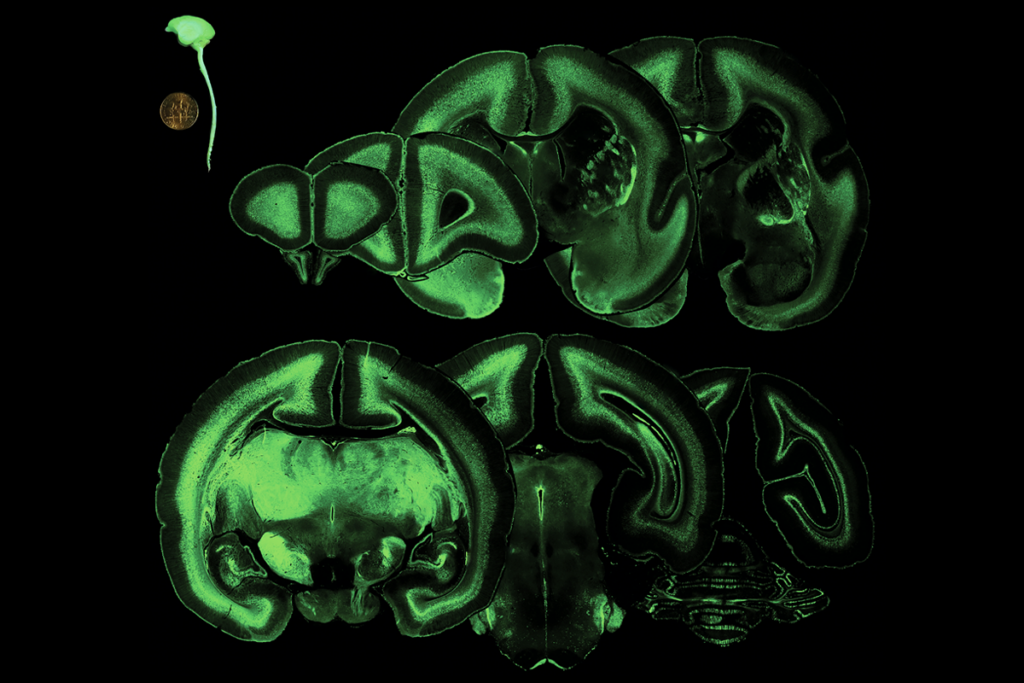

Prenatal viral injections prime primate brain for study

Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Explore more from The Transmitter

A brief history of precision self-scanning