Genetics: RNA not always a faithful copy of DNA

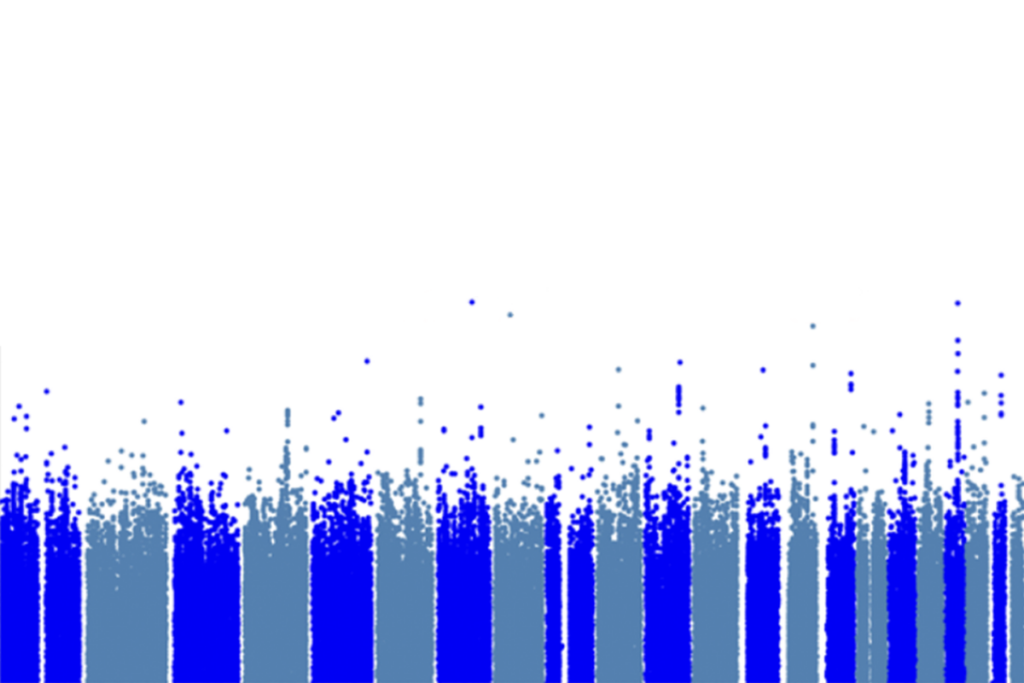

Researchers have upended a central tenet of biology by showing that there are more than 10,000 sites in the human genome where RNA sequences do not match the DNA sequences from which they are transcribed. The findings were published 19 May in Science.

Researchers have upended a central tenet of biology by showing that there are more than 10,000 sites in the human genome where RNA sequences do not match the DNA sequences from which they are transcribed. The findings were published 19 May in Science1.

Scientists generally assume that DNA sequences are faithful blueprints of the proteins produced by a cell. The new study has stirred up much controversy because it suggests that DNA is more like a rough sketch that is embellished by as yet unknown cellular mechanisms.

An enzyme called RNA polymerase typically copies stretches of DNA in the nucleus. These copies, called RNA, are then shuttled to the ribosome, the organelle that pumps out proteins. In the 1980s, scientists discovered that RNA is sometimes tweaked so that it doesn’t exactly match its DNA counterpart. But this so-called RNA editing was thought to occur only rarely in humans.

The findings point to an unexplored level of diversity in the genome that could play a role in disease. For example, some studies have linked abnormal RNA editing of receptors for the chemical messengers glutamate and serotonin to psychiatric disorders.

The researchers identified the mismatches by comparing RNA and DNA sequences from immune cells called B cells from 27 individuals whose genomes had been sequenced in the 1000 Genomes Project and the International HapMap Project. Every mismatch cropped up in at least two individuals, suggesting that they are not random changes.

The researchers also looked for this phenomenon in brain and skin cells from a separate set of individuals. Some of the same mismatches occurred in these tissues as well.

Some biologists have expressed skepticism of the study since its release. For example, they say, the mismatches could be an artifact of high-throughput sequencing machines, which sometimes make reading errors. They could also result from misreading the highly repetitive stretches of the genome.

References:

-

Li M. et al. Science Epub ahead of print (2011) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects