Cave-dwelling bats spend most of their time doing just two things: navigating and socializing.

“Those two things are not typically separated in their daily life,” says Michael Yartsev, associate professor of bioengineering and neuroscience at the University of California, Berkeley. “95 percent of their life is basically spent in these collective social environments, where they both have to move spatially, and they also have to socialize with other individuals.”

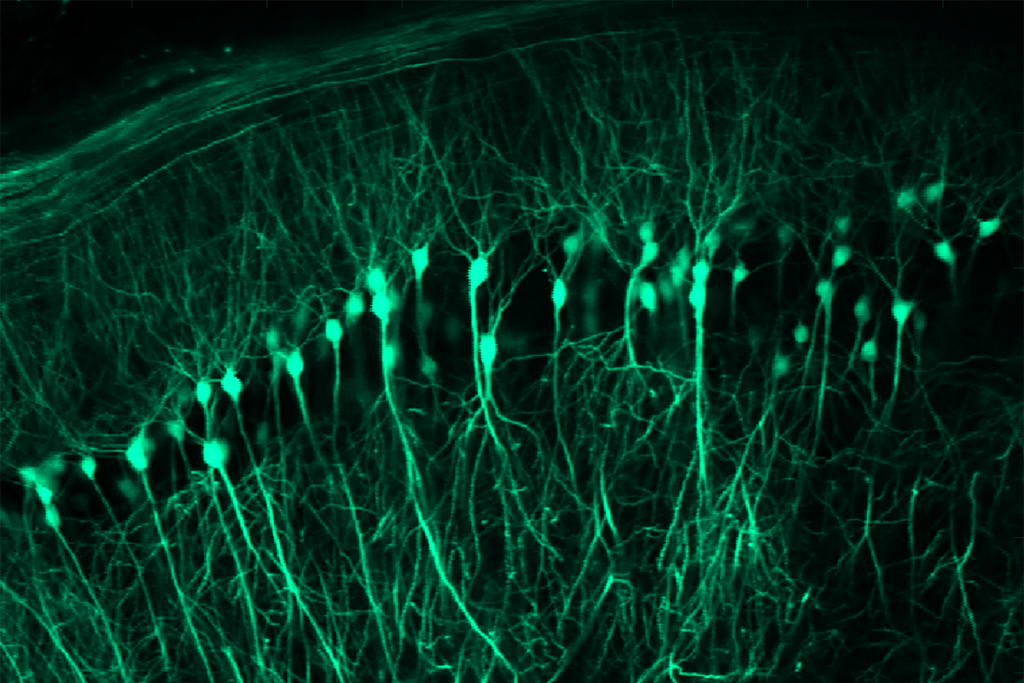

These behaviors are intertwined in the brain, too, a study published today in Science shows. Bats housed in naturalistic laboratory “caves” use a large chunk of the hippocampus, including some of the same neurons that represent an animal’s place in the environment, to encode the distinguishing features of fellow bats, including sex, hierarchy status and affiliation, the study reveals.

The hippocampal “cells are encoding a multiplex of information,” says Angie Salles, assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Illinois Chicago, who was not involved with the work.

The hippocampus is typically known for spatial navigation and the consolidation of episodic memories. Yet this new study highlights how the same cells in the hippocampus that respond to spatial stimuli also respond to bats interacting with one another and can generate sociospatial cognitive maps. “It brings it to a more holistic view of the hippocampus,” Selles says.

The hippocampus is already known to harbor social place cells, neurons that respond to the position of another animal, according to previous studies in bats and rats. Yet many of these studies were done in pairs of animals rather than in large groups, and so it wasn’t clear how the brain responds to the spontaneous behaviors of others in more complex social environments.