Interrupted sleep is typically viewed as a bad thing. Microarousals, for example—3-to-15-second-long awakenings—are associated with a number of sleep disorders.

But these fleeting wake-ups may also have an upside, according to a new Perspective article published today in Neuron. Microarousals in healthy sleep correlate with waste clearance in the brain and memory consolidation, recent rodent studies show. So the disruptions are “crucial for restorative and plasticity-promoting functions of sleep,” suggests a model put forth in the new article.

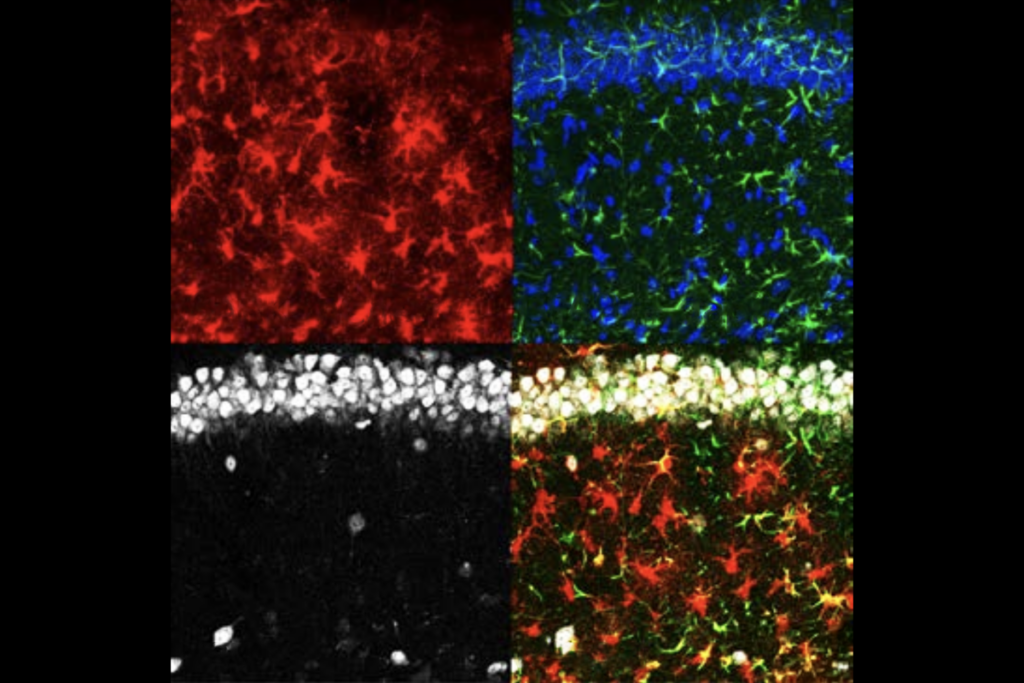

In mammals, microarousals occur frequently during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, a phase when the body’s tissues repair themselves and brain activity and heart rate slow down. These arousals track with fluctuations in noradrenaline levels, according to studies from the past five years. And during NREM sleep in mice, the locus coeruleus releases a pulse of noradrenaline about every 50 seconds.

These recent observations were surprising because “usually you associate noradrenaline with the waking brain,” says Anita Lüthi, associate professor of basic neuroscience at the University of Lausanne, who led some of the previous work and co-wrote the new Perspective article with Maiken Nedergaard, professor of neurology at the University of Rochester Medical Center. But coupled with findings Nedergaard and her colleagues published in Cell last week, the results reveal that “the system does not just operate in an all-or-none manner, but it is much more subtle,” she adds.

Overall, the conceptual model of microarousals proposed in the article is “interesting” says Bryce Mander, associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the study, but more work is needed to show microarousals are “functional rather than a correlate of another underlying process.”

I

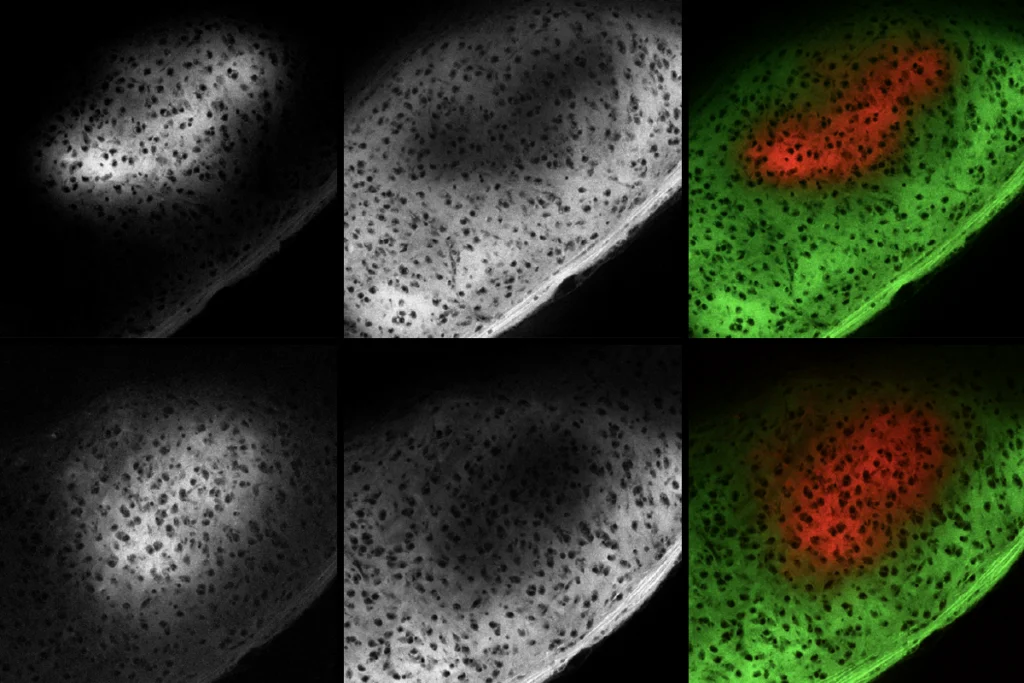

f microarousals help to facilitate waste clearance in the brain, as the article asserts, it would fill in an important blank about the glymphatic system, first described by Nedergaard in a 2012 paper.Glymphatic clearance—or the flow of cerebrospinal fluid through a network of channels in the brain that removes metabolites and toxins—increases during sleep, Nedergaard and her colleagues showed in 2013, but how sleep influences the flow was unknown. Adding to the mystery, a 2024 study found that glymphatic clearance actually slows during sleep, in contrast to Nedergaard’s findings.

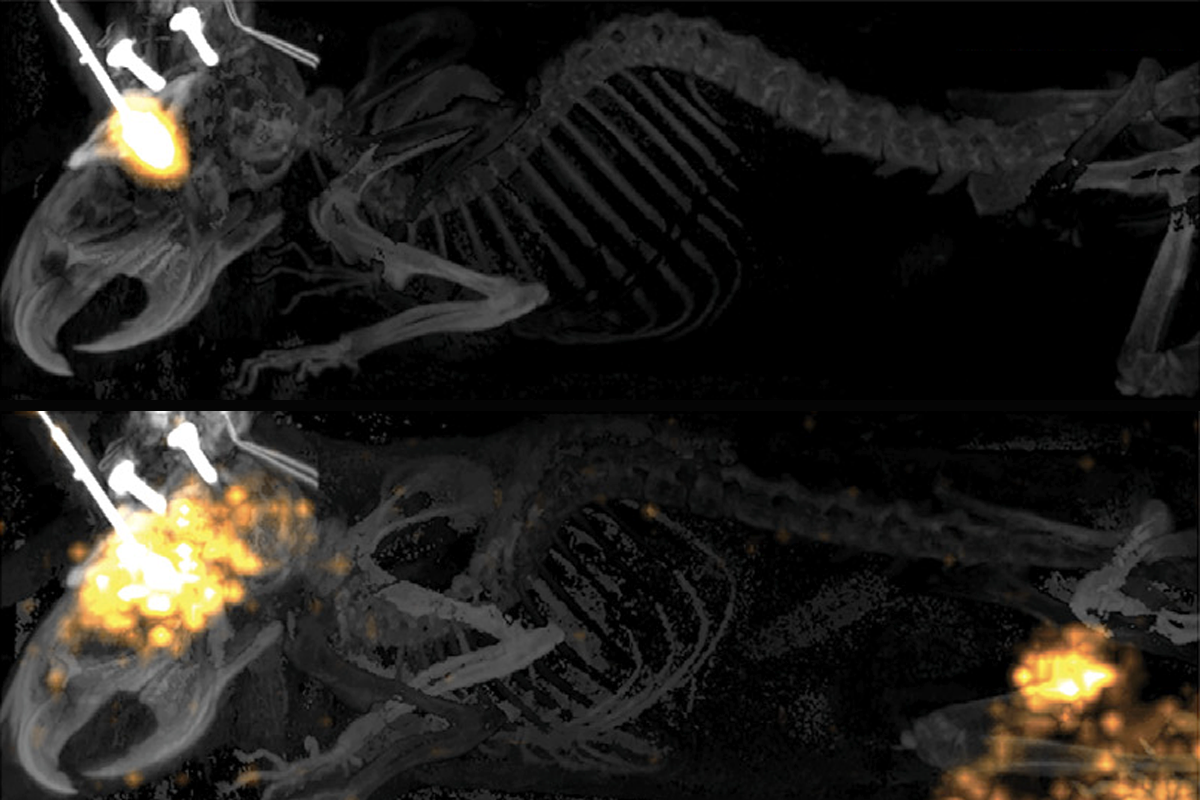

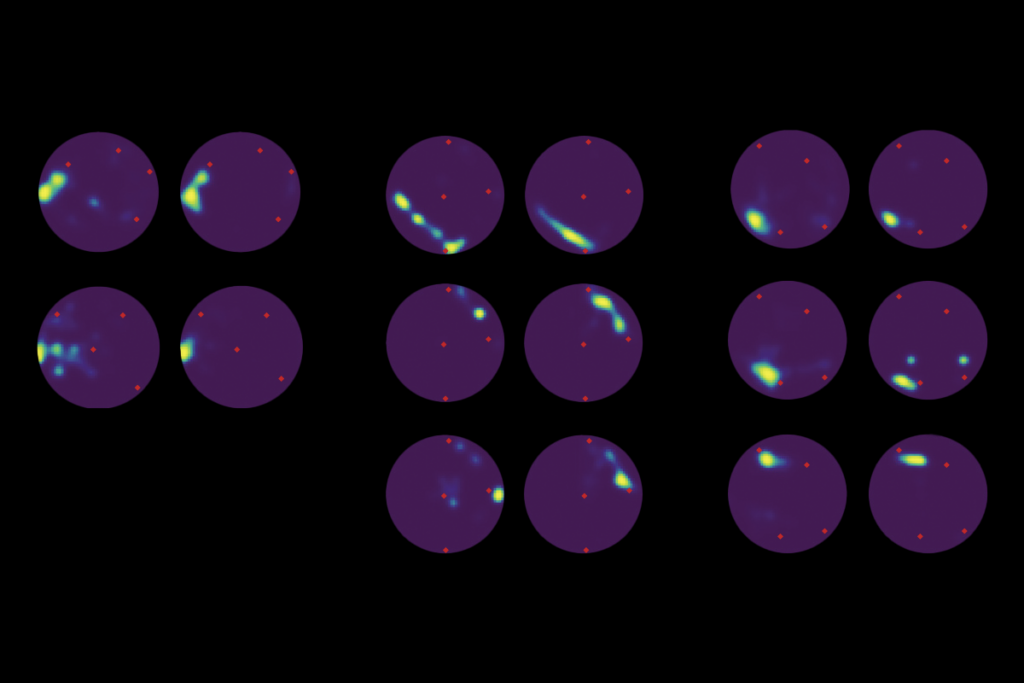

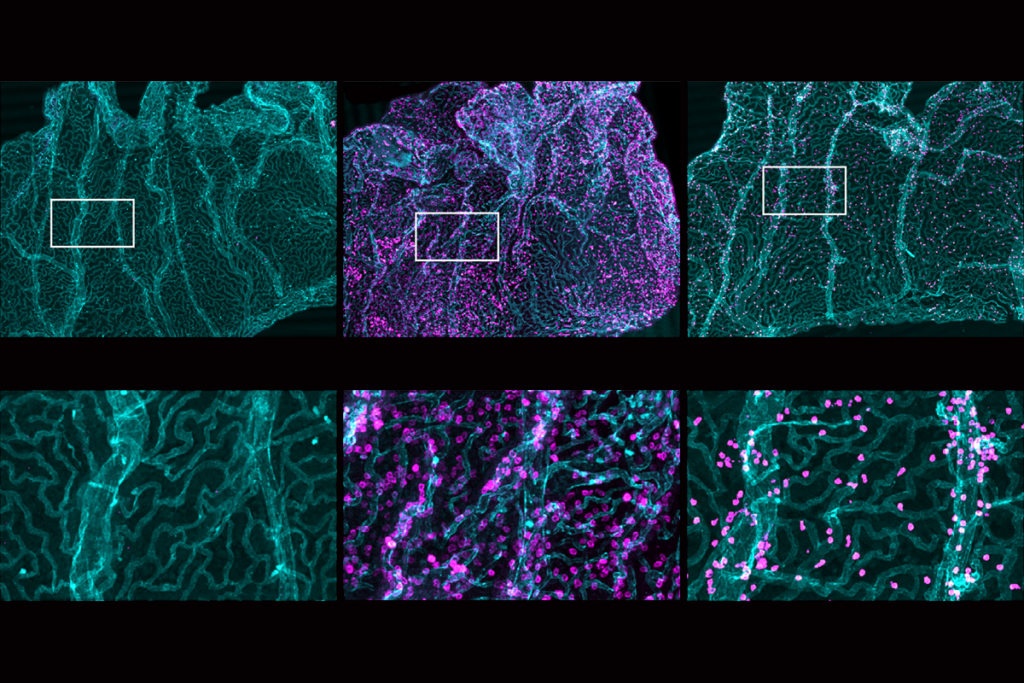

The noradrenaline oscillations from the locus coeruleus during NREM sleep cause rhythmic contractions and expansions in the brain’s blood vessels, according to the Cell study Nedergaard’s team published last week. These pulses lead to oscillations in blood and cerebrospinal fluid volumes that coincide with an uptick in the glymphatic clearance of a fluorescent tracer injected into the cerebrospinal fluid of mice.