The role of sex and gender in the brain is a popular but controversial research topic. Neuroscience has a reputation for being male-centric and focused on studying male brains, although researchers have recently embraced the idea that it is critical to study female brains as well. Generally speaking, human female and male brains are morphologically similar, but that does not suggest they don’t differ in their activity and function, or in their underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms.

In fact, sex and gender bias in neuropsychiatric conditions is the rule rather than the exception. Men are three to five times as likely as women to have autism or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, for example, and women are twice as likely as men to have anxiety or depression disorders. Understanding the biological factors and mechanisms that underlie gender- and sex-related bias in brain function and psychiatric conditions is essential to improve our fundamental knowledge of the brain and to open a path to develop novel, sex-informed treatments.

But simply including females in research studies is insufficient to resolve the role of sex and gender in neuroscience. “Sex” and “gender” are both complex and evolving concepts, extending beyond a simple binary. In practice, people are assigned female or male at birth based on external genitalia, although up to 2 percent do not belong to either category because of differences in sex development. Though gender has traditionally been co-assigned with sex—females/women and males/men—the binary nature of sex does not suffice to account for today’s expanding gender landscape. Gender exists on a spectrum, including nonbinary, gender-fluid and agender people. In transgender people, gender identity differs from gender or sex assigned at birth.

Some researchers would say that this complexity cannot (and perhaps should not) be tackled by science, and that we should stick to scientifically discernible female-male comparisons, particularly in animal research. But science should not exist in a vacuum; when detached from society, it does not serve its purpose. Indeed, in the case of gender, biology can be falsely used to fuel discriminatory laws and practices against gender-diverse and gender-non-conforming people, supposedly based on a scientific understanding of “biological sex.”

To understand how to study the influence of sex and gender in the brain in not only a scientifically accurate but socially responsible manner, we need to think of “sex” as a complex, multifactorial and context-dependent variable.

L

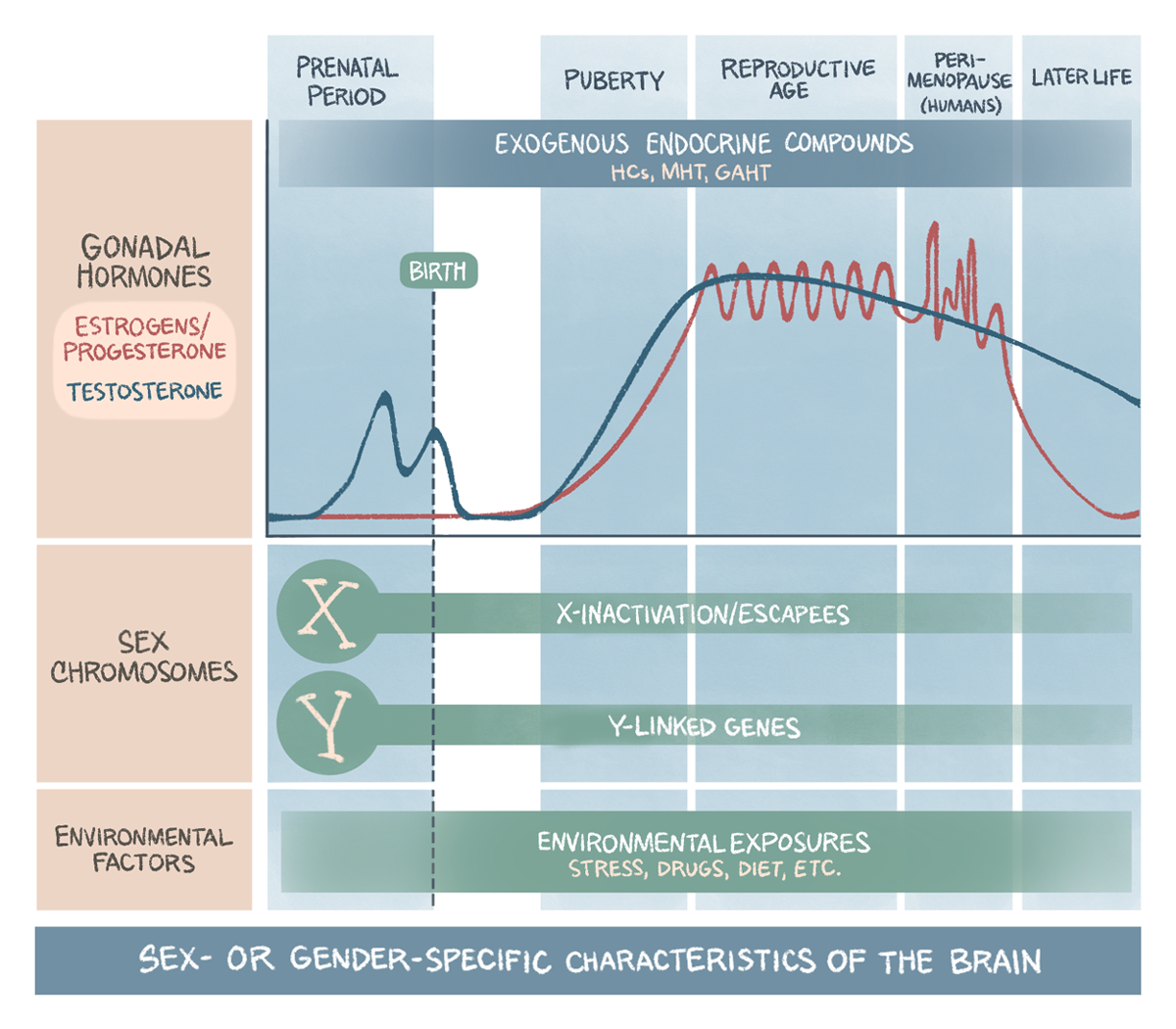

et’s say we compare female and male rodent groups and find a “sex difference” in behavior. What is the source of this difference? “Sex” is not a driver. Rather, some of the sex-related factors that determine and constitute “sex” cause the observed difference. Those sex-related factors are sex chromosomes, the gonadal hormone status and environmental factors that may or may not be gender-specific but that converge on sex-specific biology (see illustration).Sex chromosomes are primarily thought of as drivers of gonadal development: Typically, XY produces testes; XX produces ovaries. Though gonadal hormones—testosterone in males; estrogens and progesterone in females—do drive sex differences in the brain, they are only part of the story. The mere presence of sex chromosomes—such as the inactive X chromosome in females or the expression of Y-linked genes in males and X-linked genes that escape inactivation in females—can affect cellular phenotype in the brain in a sex-specific manner.

Importantly, gonadal secretions vary across the lifespan in both males and females (see illustration), providing different opportunities for sex differences to manifest in the brain. Prenatally, testicular testosterone secretion organizes and “masculinizes” the brain. During puberty, gonadal hormones surge in males and females and reorganize the brain in a sex-specific manner. Not surprisingly, a number of psychiatric disorders emerge during puberty, including an increased risk for depression in females, signaling the importance of ovarian hormone fluctuation.

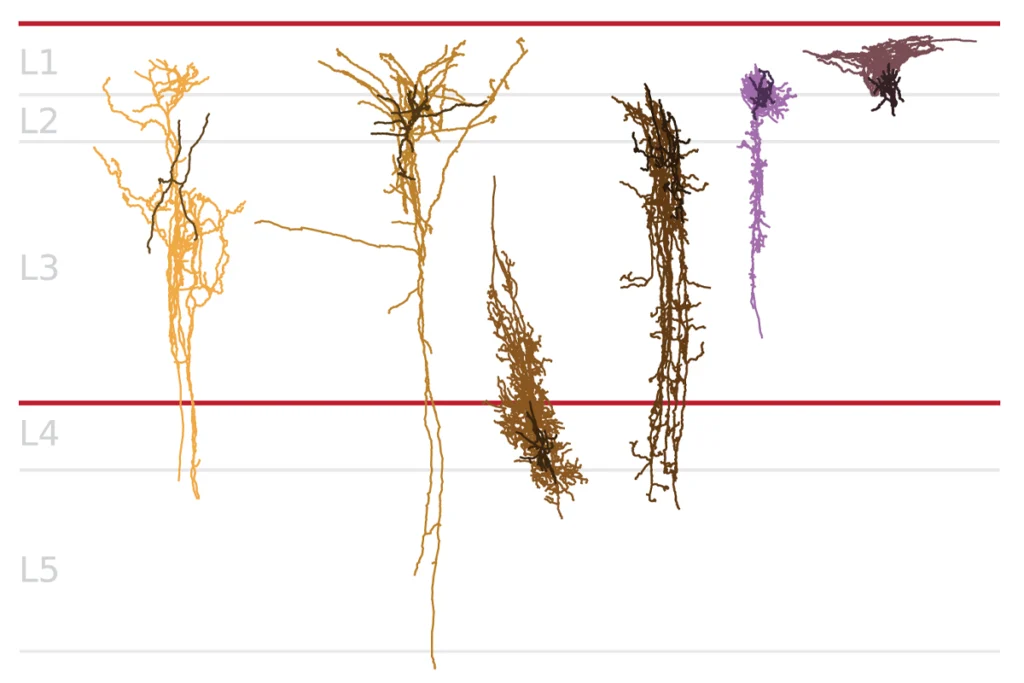

Cyclical estrogen and progesterone levels are required for reproductive function after puberty, but they also dynamically shape the brain and behavior and could protect or predispose people to brain disorders. Dendritic spine density changes across the estrous cycle in rodents, studies show, and gray matter changes across the menstrual cycle in humans. A drop in ovarian hormones in each cycle is also associated with increased depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. During perimenopause in humans, the ovarian reserve becomes depleted, accompanied by erratic hormonal changes and a peak risk for depression in women. In postmenopause, which is characterized by low ovarian hormone levels, the risk for depression in women drops and becomes similar to that in men. However, menopause triggers other disease risks—including cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and a second wave of schizophrenia—not found in men.