Repetitive behavior in toddlers may signal autism

Children who show several repetitive behaviors — such as flapping their hands or spinning their toys — at their first birthday have nearly four times the risk of autism of children who don’t show repetitive behaviors. That’s the conclusion from a study published in the March issue of the Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology.

Children who show several repetitive behaviors — such as flapping their hands or spinning their toys — at their first birthday have nearly four times the risk of autism of children who don’t show repetitive behaviors. That’s the conclusion from a study published in the March issue of the Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology1.

The report bolsters earlier findings that repetitive behaviors may be among the earliest-emerging signs of autism2. The researchers also showed that a simple parent survey taken at home is enough to flag the behaviors.

The study looked at younger siblings of children with autism — so-called baby sibs — who are at 20-fold higher risk of autism than children in the general population.

Intriguingly, the study found that all baby sibs, regardless of later autism diagnosis, show more repetitive behaviors than the low-risk controls do. And children who show many repetitive behaviors, whether they are high or low risk, are 3.6 times more likely to be diagnosed with autism later on.

Wiggling arms and babbled syllables are mainstays of a baby’s behavioral repertoire, as are a toddler’s love of routine or endlessly replayed cartoons. Children’s fondness for this kind of repetition can resemble the restricted, repetitive behaviors seen in people with autism, which are among the core features of the disorder.

The similarity has made it difficult for researchers to distinguish symptoms of autism from typical milestones of development, and to track when and how repetitive behaviors arise. The results of this study may begin to untangle the timeline.

The repetitive behaviors seen in the new study are present at 12 months of age. “[That] means they are certainly present in the first year of life,” says lead investigator Joseph Piven, professor of psychiatry, pediatrics and psychology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We’re beginning to understand the timing of the unfolding of these behaviors early on.”

Repetition rating:

The search for early social deficits has garnered substantial attention from researchers, but ritualistic, repetitive behaviors have largely been neglected. That’s unfortunate because repetitive behaviors are often easier for a parent to notice than the absence of a social behavior such as crying to be held.

The researchers analyzed repetitive behaviors in 190 baby sibs and 60 controls at 12 and 24 months of age. The high-risk children in this study came from four centers that are part of the Infant Brain Imaging Study.

“It’s one of the largest samples to look at this age group,” says Jason Wolff, research associate at the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

The researchers used a parent questionnaire called the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R), designed to assess autism traits in toddlers and preschool-age children.

The 43 questions capture six categories of behaviors, ranging from simple motor behaviors such as flicking objects with the fingers to more complicated ones — insisting the handle of a mug must be turned at an exact angle at mealtime, for example.

Even with this relatively brief questionnaire, parents identified those children who went on to be diagnosed with autism as having more repetitive behaviors at 12 months of age than the other children.

When the children were 2 years old, the researchers also assessed them for autism traits using the checklist in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and two other tests. At that time they classified 41 of the high-risk children as having autism, recognizing that more of this group may be diagnosed as they mature.

On average, the children diagnosed with autism, whether baby sibs or controls, had about six repetitive behaviors across many categories compared with one or two behaviors in the children who are not diagnosed with the disorder.

“For the children with autism it looks like it’s a little bit more global, where many different parts of their day may be fixed, and ‘inflexible’ takes on a new meaning,” says Wolff.

The same behaviors take on a slightly different aspect in children with autism, something other researchers say they have also noticed.

”The behavior [in typical children] is embedded in more social behavior, such as a child who spins and laughs and looks to his mom, versus a child with autism who spins all by himself,” says Catherine Lord, professor of psychology in psychiatry and pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medical College, who was not involved in the research.

The results also support previous findings from Lord’s team of an association between repetitive behaviors and autism traits in children up to 4.5 years of age3. To see similar results in 12-month-old children, she says, “is good news and more confirmation of the validity of the RBS-R.”

The study highlights an early behavioral feature of autism and points to new avenues of inquiry. “The next question to explore is why some children with early repetitive behaviors go on to develop autism and others don’t,” says Wendy Stone, professor of psychology at the University of Washington in Seattle, who was not involved in the work.

Still, it’s too early call the behavior a biomarker for the disorder, Stone says.

“We can’t say from this study whether repetitive behaviors can be used effectively to screen for autism in young children,” she says. “Identifying behavioral differences between groups of children is very different from identifying predictors of autism.”

References:

1: Wolff J.J. et al. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Epub ahead of print (2014) PubMed

2: Damiano C.R. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43, 1326-1335 (2012) PubMed

3: Kim S.H. and C. Lord Autism Res. 3, 162-173 (2010) PubMed

Recommended reading

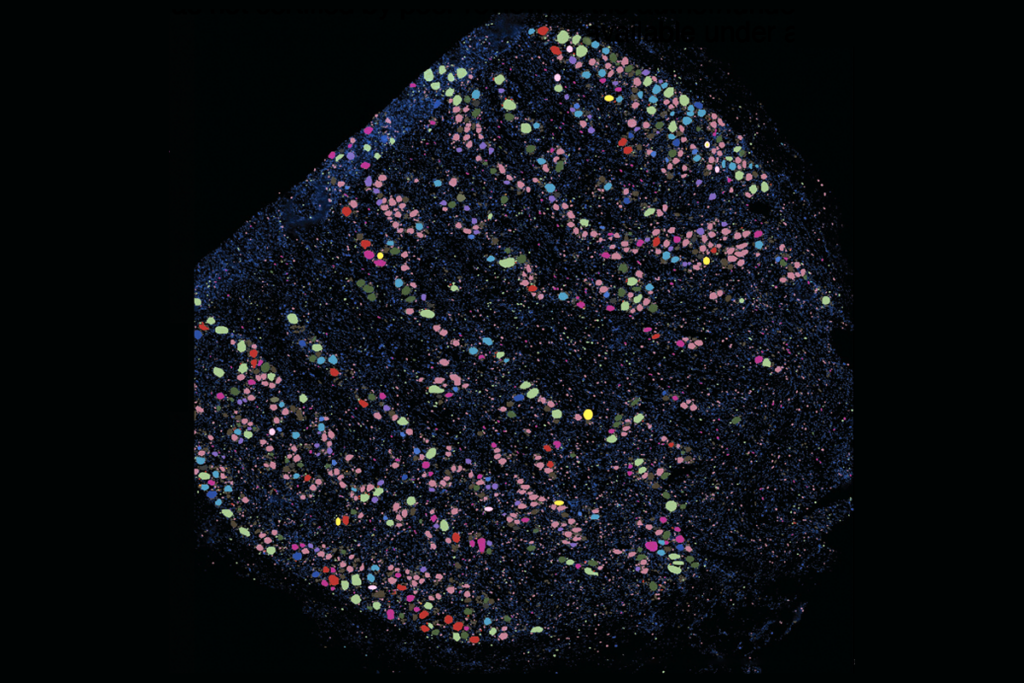

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models