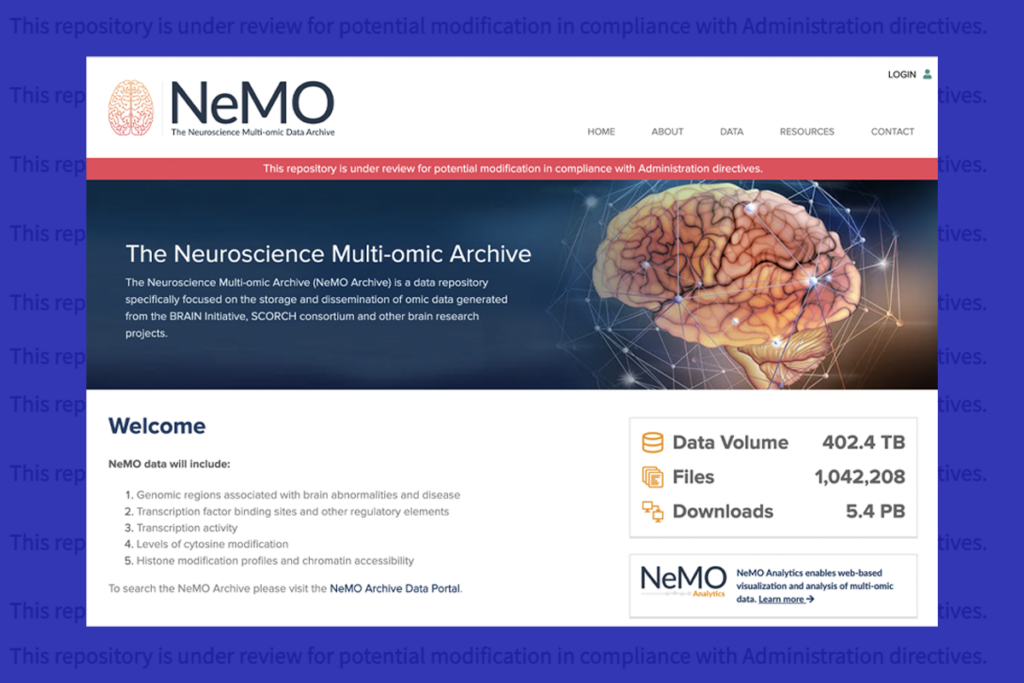

The United States faces a terrifying prospect: the destruction of multiple parts of its national scientific infrastructure. Open datasets are shutting down, including decades of climate tracking at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and health information at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—a loss of particular concern to neuroscience. Federally funded publications that contain certain keywords, such as “women” and “bias,” have been banned. And, according to some observers, Pubmed may soon be flooded with unscientific anti-vaccination “papers.” Even some independent charitable organizations show worrying signs of capitulating to the insane and anti-scientific demands of the new administration, possibly out of fear of losing their tax-exempt status: The Howard Hughes Medical Institute cut funding aimed at making science more inclusive, as did the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

Science internationally has come to depend on this imperiled infrastructure, and the ripple effects of the implosion of scientific institutions in the U.S. could be devastating worldwide.

It is tempting in the face of this damage to wish, desperately, to go back to the way things were before. But not only is this ineffectual, as the new U.S. administration will be in power for at least four years (and longer is certainly possible), it is a failure to learn the lesson of this moment: We must stop relying on scientific infrastructure provided by one nation or organization. Any single point of failure makes science fragile. Instead, we need multiple organizations across as many countries as possible, collectively providing access to overlapping data and services, so that the loss of any one or several of these doesn’t stop us from doing science. There are some short-term steps we can take to protect ourselves, but we also need to start the work of building resilience for the long term.

H

ow did things end up like this? Part of the problem is that building and maintaining any sort of infrastructure is difficult and expensive, and, for most scientists, it doesn’t match our skill sets or inclinations. Understandably, we’d rather let someone else do it so that we can focus on the science. But this puts us in a vulnerable situation, and this is not the first time we are feeling the consequences of that.A dramatic recent example is Twitter. Many scientists put huge efforts into building networks to communicate with colleagues and the general public. But all that work and the value in those networks was lost when many scientists felt compelled to leave following Elon Musk’s takeover of the platform (now X). The process of rebuilding on Bluesky is underway, but it will take years and may never reach the same critical mass. Even if the transition is successful, the same thing may happen to Bluesky in a few years.

It’s not just social media: We see the same issue happening in some of the core institutions of science. Historically, scientists owned and ran their own journals, but they were persuaded to sell them to publishers in the 1950s to 1960s. These publishers merged into only a few companies and increased the costs of publishing dramatically, giving rise to some of the highest profit margins in the world. More worryingly, the companies took control away from scientists. Even when we are certain that a paper is fraudulent, it often takes years before it is retracted, if ever—because retractions are simply not good for business. Most big science publishers are based in Europe, but a huge percentage of their revenue comes from the U.S. If the Trump administration demanded that these publishers block unapproved publications from the U.S., would they stand and fight?

Even preprint servers such as arXiv and bioRxiv may be vulnerable because they are registered in the U.S. If they do stand firm, their hosting providers may be a point of vulnerability. In 2024, arXiv ceased mirroring its data and switched to a San Francisco-based cloud provider. And what of other essential servers? How disruptive would it be if GitHub started deleting repositories, or Google Scholar started hiding certain papers in response to U.S. government demands? After all, Google has already shown itself quite happy to rename entire seas to cater to Trump’s whims.

S

o what can we do? In the short term, we should try to use a more diverse range of services located in multiple countries. European Union versions (such as Zenodo instead of OSF for depositing data and manuscripts, or EuropePMC instead of PubMed Central) are a good start because the EU is a multi-country organization. We shouldn’t stop there, though, because even the EU has shown itself to be vulnerable to political and corporate influence—as, for example, when they were poised to mandate open-access scientific publishing in 2007 but watered it down at the last minute after intense industry lobbying.We also need to start integrating services that are resistant to interference into our daily workflows. PubPeer is a post-publication peer-review service widely used by science “sleuths” to share evidence of fraud. With wider adoption, and ideally registered outside the U.S., it could make the scientific literature resistant to the sort of influence the U.S. government is attempting. You don’t need to rely on the journal if the commentary of the scientific community is open and visible to all on every paper. eLife offers an intermediate approach, making a publication decision before review and then making the review and revision process fully transparent. On social media, Mastodon is managed and run by the community (e.g., neuromatch.social is a server run by neuroscientists) and is robust by design. It is slightly more difficult to use, understandably putting many people off, but this is rapidly improving.

In the longer term, we need to build out robust infrastructure in a more rigorous and systematic way. Some of this can be done by the developers of existing services, adding capabilities to protect against the possibility of themselves being compromised. For example, the platform Research Equals includes a “poison pill” agreement among its shareholders to make it more difficult to be sold off. Other approaches could include facilitating and encouraging openly sharing and licensing your code and data so that new services could be spun up easily in case of compromise. bioRxiv, for example, publishes an easily downloadable feed of all its data.

Ultimately, we need to start building new multi-country organizations, designed from the start to be community-run and resilient. A coalition of university libraries could be ideally placed to lead this effort, as they already have vast experience building for and supporting access to scientific data and publications. Just imagine a world in which universities mutually support one another by building scientific infrastructure based on free sharing, giving every country, from the poorest to the richest, secure access to the scientific data that can change the world for the better. This isn’t fanciful. It can happen, but we have to put the effort in, because nobody will do it for us.