NIH seeks input on how structural racism affects brain research, health

The feedback could lead to “novel ways” to conduct studies and reduce health disparities, a National Institutes of Health employee says.

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a request for information last week about how to counteract the effects of structural racism on brain health and research.

The request, or RFI, seeks comments from scientists on “(1) the impact of structural racism on brain, cognitive, and behavioral function across the lifespan and (2) the role of structural and systemic racism on the conduct of brain and behavioral health research,” the announcement states. The NIH also “encourages” patient advocacy groups, health-care providers and “people with lived experience of brain or behavioral health disorders” to share their thoughts, the notice states.

“We really wanted to solicit feedback on how best to address these lofty goals,” says Elizabeth Hoffman, who co-led the inquiry and is associate director of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). “One hope from this is that we can—to the extent possible—move away from some of the tried-and-true approaches for conducting research and to think about novel ways to answer some of these questions and to think about ways to collaborate with researchers in other disciplines.”

NIDA issued the request alongside the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). The four institutes plan to accept comments until 14 June.

The RFI follows a May 2022 workshop hosted by the four institutes, as well as several funding opportunities focused on how structural racism contributes to substance misuse and health disparities. Structural racism refers to the unjust treatment and oppression of racial and ethnic minoritized groups through the systems and policies that shape society, including housing, employment, education, health care and the criminal justice system.

Several neuroscientists who study the effects of racism on the brain told The Transmitter they felt cautious optimism when they read the RFI. “I love that they’re asking for information and input,” says Michael Yassa, professor of neurobiology and behavior, and director of the Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory at the University of California, Irvine.

The RFI is “long overdue,” says Negar Fani, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University. “I’m hopeful and also a little bit skeptical.” The request “shows that there’s interest on the behalf of the NIH,” she adds, “but I think that the proof is in the pudding.”

F

or most of the field’s history, neuroscientists have often used race incorrectly in their research or ignored it entirely, says Oliver Rollins, assistant professor of ethnic studies at the University of Washington and a sociologist who studies race and neuroscience. Early, racist studies attempted to use race to explain variations in brain structure or behavior, he says, and later studies tried to correct for that by not considering race as a factor at all.“As they moved away from race, they were really also moving away from thinking about how race leads to structural inequalities or racism,” Rollins says, and thus how structural racism contributes to different health and behavioral outcomes. “We know racism really does matter. We just do not know how to quantify it, how to put it in a model, how to bring it into what we’re doing.”

This distancing led to the knowledge gaps mentioned in the RFI about how experiencing structural racism affects health, Fani says. By contrast, she adds, there is a deeper pool of studies that capture the relationship between poverty or other structural inequalities and disease risk.

Rollins says he is curious about how the NIH will use the comments and findings from future racism-focused studies, particularly if they demonstrate that structural racism has a negative impact on the brain. “I don’t think anybody would be surprised by that. So then the question becomes, what is it that we’re trying to show by saying that racism does have this effect?” Rollins says.

The RFI also invites comment on how structural racism has seeped into methodology and study designs. One example of this is how some scientists group people based on race and ethnicity in their data analysis, says Ruth Shim, professor of cultural and clinical psychiatry and associate dean of diverse and inclusive education at the University of California, Davis.

Since 2001, the NIH has required the researchers it funds to report the race and ethnicity of participants in clinical research. But this has had an “unintended consequence” of prompting researchers who hadn’t spent much time thinking about race or racism in the past to start “thinking in more racialized ways about research,” Shim says, even in studies that have nothing to do with race, which “is problematic because then people start to ascribe racial explanations if there are differences” among participants.

Because most neuroscientists do not typically interact with sociologists or other experts in the humanities, they may not understand that race and ethnicity are socially constructed and not rooted in biology, says Marybel Gonzalez, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral health at Ohio State University. Last month, Gonzalez co-wrote a perspective paper with recommendations on how to use race and ethnicity categories more responsibly in neuroimaging studies.

“We start to believe that these categories of whether you’re Black, white or Hispanic actually translate to biological differences,” Gonzalez says. “And that’s wrong.”

H

offman says she cannot comment on whether the RFI might lead to specific funding opportunities, but she hopes the information gleaned from it will help “develop strategies for addressing some of these research gaps.”If the request does lead to new funding, Shim says, she would like to see that money given to community organizations that partner with researchers, rather than directly to research institutions, a model the NIMH deployed in a new funding program at the end of 2023.

Yassa, from the University of California, Irvine, says he recently shifted his research approach to include more community collaboration. His lab studies the vascular risk factors associated with Alzheimer’s disease, which are overrepresented in racial and ethnic minoritized groups. To reach more people in the Latino community, Yassa and his team translated their recruitment materials into Spanish and have spent the past year building relationships with organizations and people in the Orange County and Santa Ana areas, he says.

“We thought we would flip this a little bit and go out into the community and do a lot of listening and a lot less talking and try to really understand peoples’ experience,” Yassa says. “That’s been very successful. We formed a lot of strong partnerships.”

On the infrastructure side, Fani says it would be “tremendously helpful” to have an office within each institute—similar to the overarching National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities—that focuses on health disparity and racism research. The office could also oversee the grant review process.

Another valuable resource would be a set of research principles to guide study designs, Fani adds, like the research domain criteria the NIMH developed for studies on mental conditions. “They’re measures that we know our colleagues are using; we can share data; we can replicate findings,” she says. “It’s very powerful, and if we had a similar thing for structural and individual racism, that would be a huge step forward.”

Regardless of what comes out of this RFI, Yassa says he hopes more neuroscientists think about the structural inequities that contribute to brain health. “It has to be integrated into everybody’s work, in addition to having a deep focus on it in some individuals’ work.”

Recommended reading

Without monkeys, neuroscience has no future

What U.S. science stands to lose without international graduate students and postdoctoral researchers

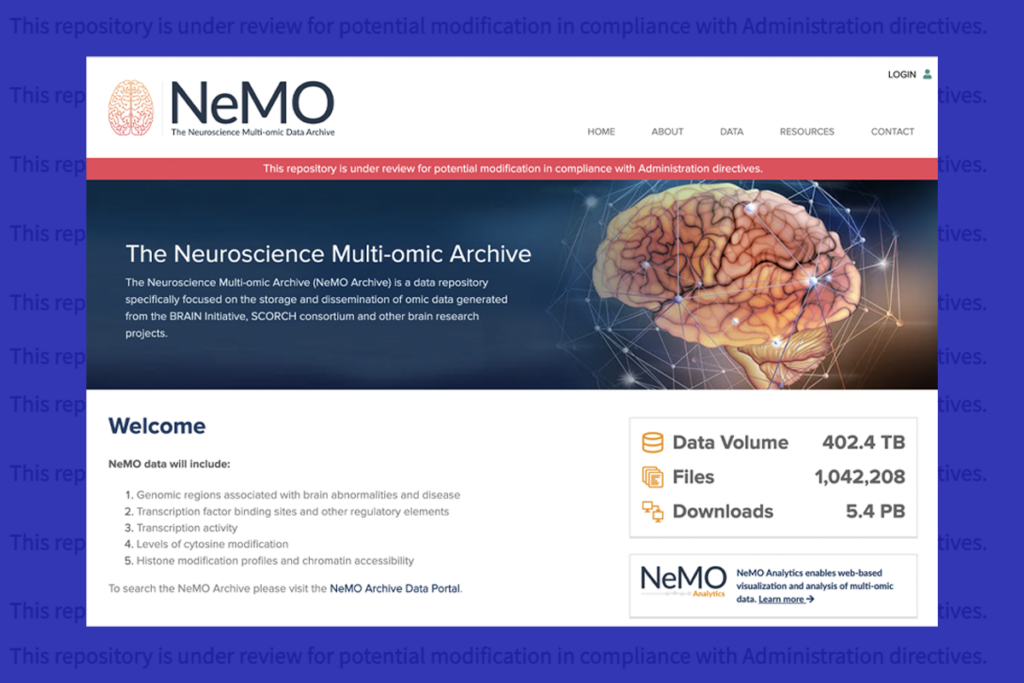

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025