Exclusive: NIH appears to archive policy requiring female animals in studies

Such a shift would “put us back in the dark ages in terms of our science,” says neuroscientist Anne Murphy, who helped to formulate the original policy.

The phrase “Historic document published prior to January 20, 2025” now appears on multiple websites of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) that pertain to its long-standing policy on research into sex differences. The move could signal a shift away from research that considers the roles of sex and gender in biology and health, several neuroscientists told The Transmitter.

“I just felt my heart sink when I saw that—I don’t understand why you would want to change a policy that clearly has had a positive impact on the integrity and reproducibility of basic science studies,” says Anne Murphy, professor of neuroscience at Georgia State Institute, who was part of the subcommittee that helped formulate the original policy. Abandoning the policy would “put us back in the dark ages in terms of our science,” Murphy says.

The “Sex as a Biological Variable (SABV)” policy, issued in 2016 by the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, requires NIH-funded researchers to include both males and females in their vertebrate animal studies or explain why they don’t.

It is unclear how the new labeling affects adherence to the policy, and there has been no official statement on it from the NIH. Jill Becker, professor of neuroscience at the University of Michigan, says an NIH program officer told her that if the request for applications asks for an SABV statement, researchers must include it in their proposal.

The policy’s labeling change occurs alongside other developments, such as NIH officials searching grants for words that were previously flagged by the National Science Foundation, including “female,” “gender” and “women,” to ensure that the grants do not violate President Donald Trump’s January executive orders that recognize only two genders and terminate activities aimed at advancing diversity, equity and inclusion.

“It’s very troubling to see, based on everything else that has been happening,” says Zoe McElligott, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

P

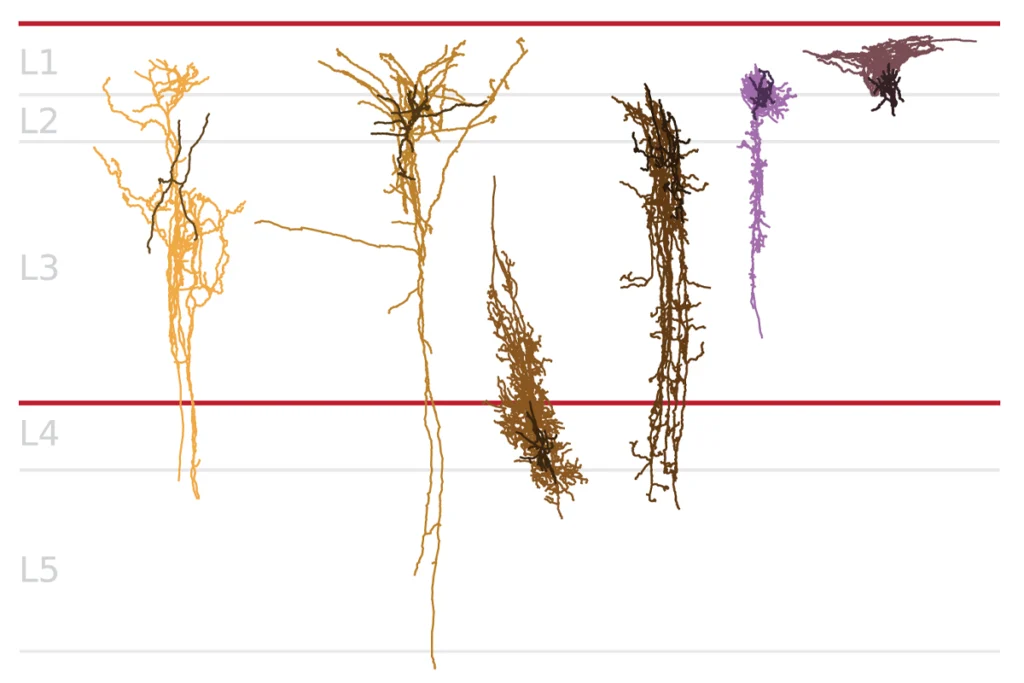

rior to 2016, most researchers—especially neuroscientists—excluded female animals to avoid any variability in behavior and physiology that could be associated with hormonal changes during the estrus cycle. But “without knowing how the sexes are alike and different, function similarly or differently, and respond to treatments similarly or differently, our knowledge base is incomplete,” wrote Janine Austin Clayton, director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health, in 2018. Clayton and her office did not respond to The Transmitter’s email requests for comment about the new label applied to the SABV policy.After the policy was implemented, it spurred several important research endeavors and findings in neuroscience, McElligott says. For example, she has found that neurotransmitter release modulates alcohol consumption differently in male and female mice. Other sex differences have been found across brain areas, synaptic plasticity mechanisms and learning strategies. “Looking at sex as a biological variable gives you the spectrum of biological possibility and how biology is working,” she adds.

The policy is typically enforced at the level of study sections, the meetings in which grants are reviewed. “That’s where we would see if there were any real changes or not,” says Margaret McCarthy, professor of pharmacology at the University of Maryland.

But most of these meetings have been postponed or canceled since Trump’s inauguration, mainly because of the new administration’s freeze on NIH communications and an “indefinite hold” on submissions to the Federal Register, which are necessary to conduct the meetings, The Transmitter has reported. Until grant reviews resume or until the NIH provides an update regarding the SABV policy, scientists— particularly those who study sex differences—are in the dark about the policy’s future.

Still, Murphy says she hopes that the almost 10 years of the policy have been influential enough to change neuroscientists’ view on the use of sex as a biological variable in research. “If they do reverse the policy, I hope that people will recognize the importance of having this and will continue to include males and females in their studies.”

Recommended reading

Without monkeys, neuroscience has no future

What U.S. science stands to lose without international graduate students and postdoctoral researchers

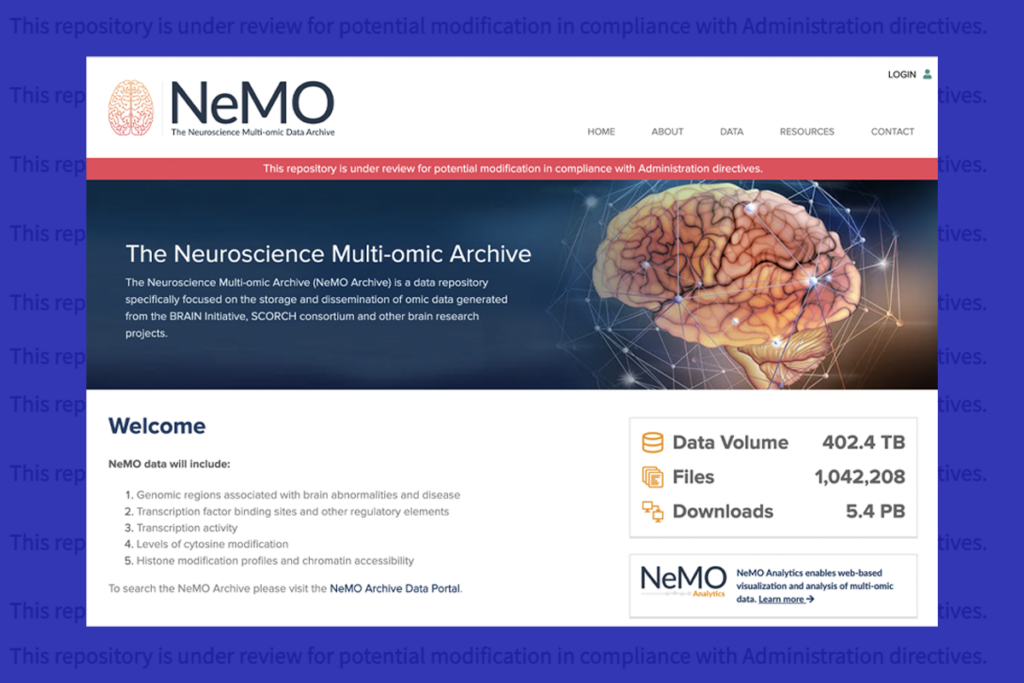

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuroscientists reeling from past cuts advocate for more BRAIN Initiative funding