More than two decades ago, a physicist walked into a bar in a Montana town. The physicist, Dmitry “Dima” Rinberg, was attending a neuroscience conference held at the town’s ski resort, and he found himself at something of a professional crossroads. He had a Ph.D. in the wave dynamics of superfluid helium but had realized he wanted to move into a field where he might break fresh ground. At the time, he was investigating sensory systems in cockroaches at the NEC Research Institute in Princeton, New Jersey.

In the bar, Rinberg struck up a conversation with a man named Alexei Koulakov, who was surprised to meet another physicist attending the conference. The men soon realized they also shared a similar life trajectory: They were both expatriates from the former Soviet Union and had grown up in Moscow, and both were looking to move beyond theoretical physics. By the time they finished skiing the next morning, they had become close, Rinberg says.

In the years that followed, both men shifted into studying the neuroscience of olfaction and became collaborators, with Rinberg building devices and performing experiments, and then developing theories with Koulakov. Even though it is thought that olfaction was one of the earliest senses to evolve, scientists know less about how we perceive smells than about vision or auditory processing. Joel Mainland, a member of the Monell Chemical Senses Center and adjunct associate professor of neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania, notes that science has “not spent the same amount of time and resources on understanding olfaction” as it has on other senses.

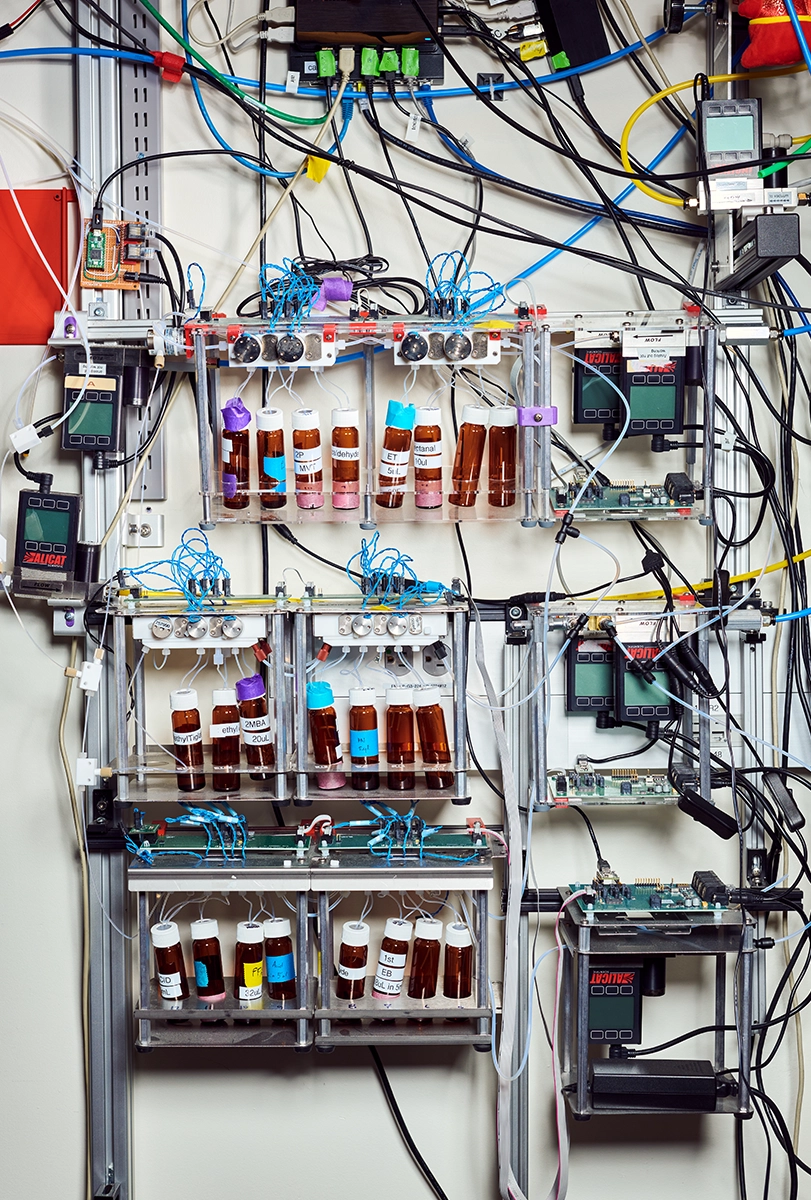

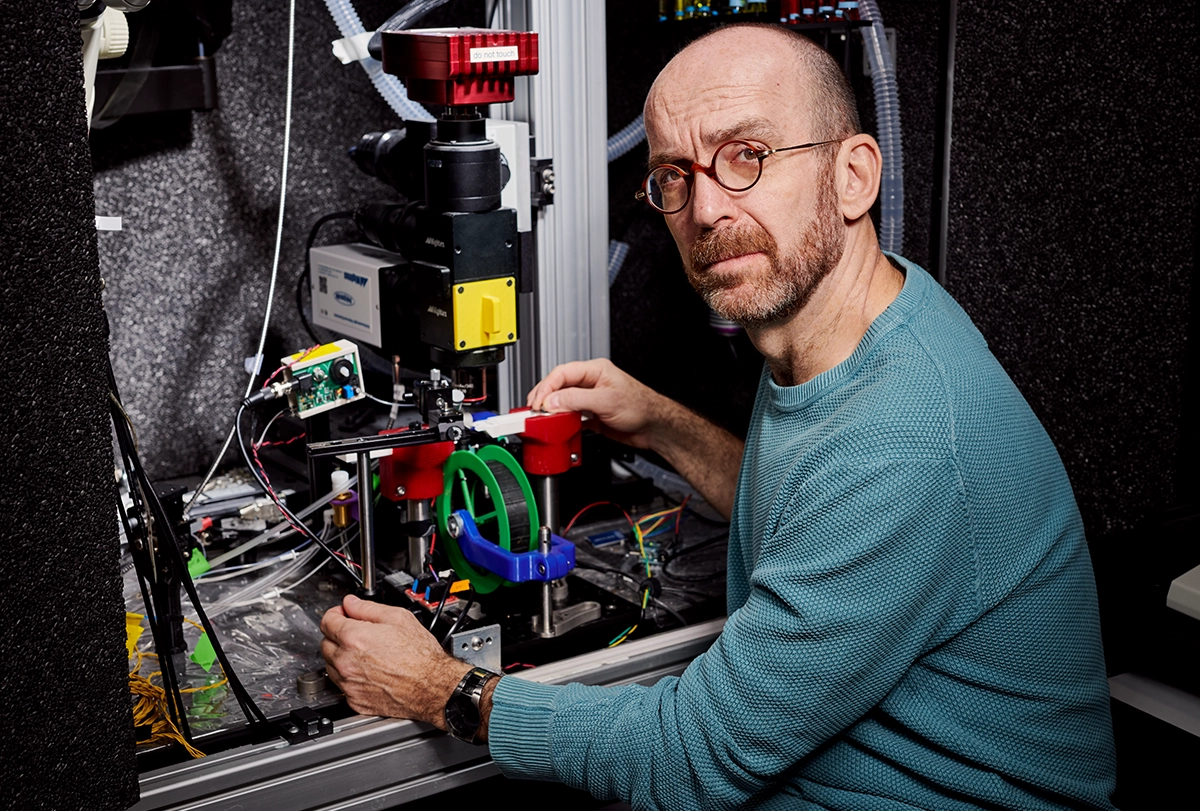

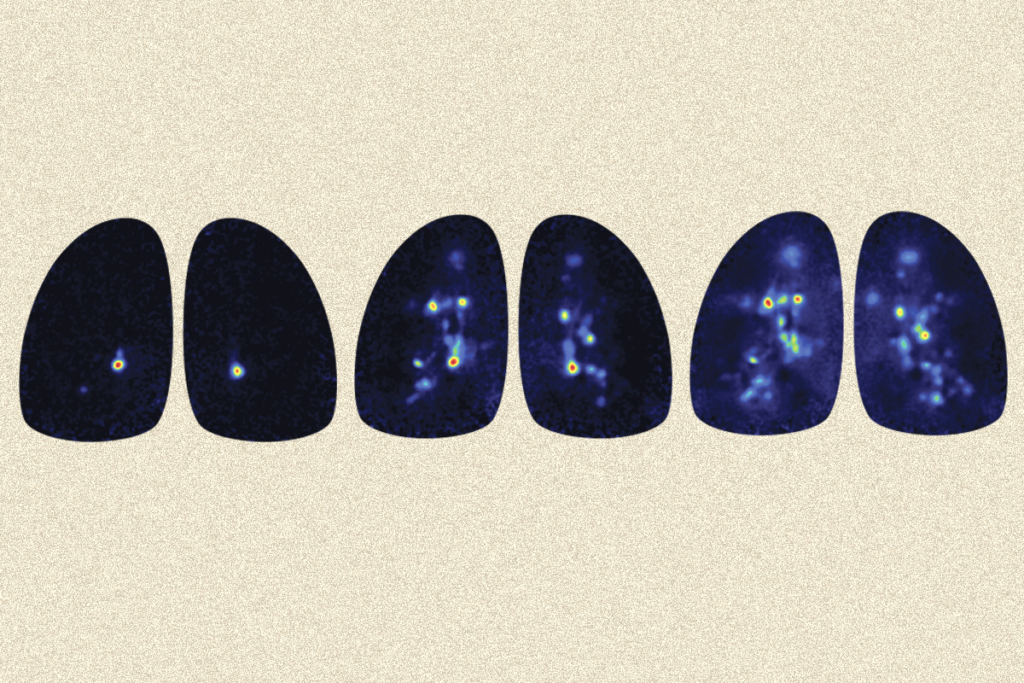

Today Rinberg heads an olfactory research lab at New York University and leads a consortium at the National Institutes of Health called Cracking the Olfactory Code, which includes seven labs across the United States. Over the years, in collaboration with Koulakov and others, he has found evidence for what is called the primacy coding theory—a much-needed effort, given the hole in our knowledge of smell. But he has also leaned on his physics background to build scores of devices to deliver odor stimuli. These “olfactometers” are one of Rinberg’s “many contributions to the field,” Mainland says.

R

inberg was born into a Jewish family in Moscow in 1966 and remembers himself as a shy but happy child. In his early years he excelled at math, which his father supported by presenting him with textbooks. But despite his academic talent, a career in research was not guaranteed.The Soviet government had a history of limiting access to higher education for Jewish students. For instance, in the 1970s and ’80s, at least three Soviet colleges were found to give difficult entrance exams to Jewish applicants, designed to effectively reject them. These colleges failed Jewish applicants on oral entrance exams by asking them so-called “killer questions” or “coffin problems”—mathematical queries that required extremely specific answers or were followed by questions of increasing difficulty. According to one report, the number of Jewish students in Soviet universities declined from 74,900 in 1935 to about 45,800 in 1960.

Against this backdrop, Rinberg’s mother explained to him when he was 9 that he would “have to work extremely hard to get anywhere,” he says. He heeded her advice and graduated in the top of his class before applying to Moscow State University’s Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics. He thought he had done all he could, so it was even more painful when he did not get in. Instead, he pivoted to the Moscow Institute of Steel and Alloys (today the National University of Science and Technology MISIS), an institute with a constant need to train steel engineers and with fewer applicants, so Jewish students were accepted. There, he thrived.

During that time, Rinberg met his future wife, Tanya Tabachnik, while they were both preparing for a multi-week backpacking trip in the Tian Shan mountains in central Asia. Tabachnik was a serious student herself, studying electromechanical engineering at the Moscow Machine and Tool Institute, but even she was impressed by the enthusiasm and passion with which Rinberg talked about science. “I didn’t know people could love their studies so much,” she says. They married in 1989.