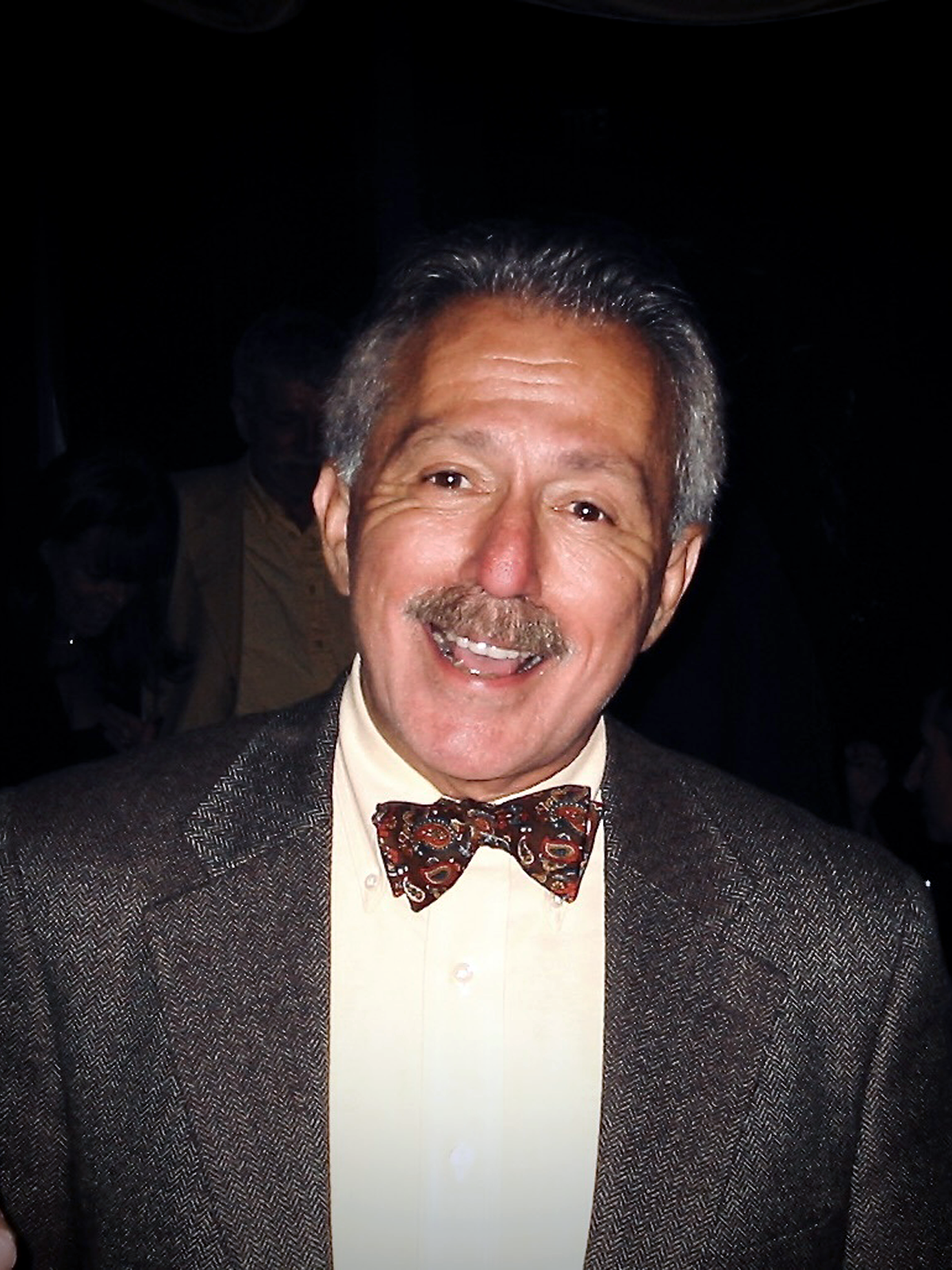

When Floyd Bloom was in high school in the early 1950s, he took an aptitude test, and the results suggested he would excel at jobs in communication, such as journalism or advertising.

But that was not what his family envisioned for him. His father, who had wanted to be a doctor himself and who revered the profession, pushed for medical school. And so Bloom attended medical school at Washington University in St. Louis, followed by an internal medicine internship at nearby Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and then took a research position at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C. It was at St. Elizabeths that he got hooked on scientific inquiry, and he abandoned the thought of becoming a doctor.

It turned out that Bloom, who died on 8 January, did indeed have a skill for communication—science writing in particular. He authored or co-authored 32 books and monographs, more than 650 papers, and co-authored the textbook “The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology,” first published in 1970 and still in print today.

The textbook quickly became “a place where you could go to for all the information you needed on a given neurotransmitter system and how it relates to neurocircuitry,” says John Morrison, professor of neurology at the University of California, Davis and a former postdoctoral fellow in Bloom’s lab. “I can’t think of another book as important to a graduate student in neuroscience.”

B

loom was born on 8 October 1936 in Minneapolis. His father was a pharmacist. His mother had emigrated to the United States from Russia at 9 years old. The U.S. declared war on Japan when Bloom was 5, and during the austerity of World War II, his family used rationing stamps for groceries, and he marched with classmates in parades to raise money for war bonds.After the war, his family moved to Dallas, Texas, where Bloom’s father and uncle opened a drug store. In high school, Bloom served as student manager of the school’s baseball and football teams, bringing water and towels to the players. In 1953 he graduated second in his class. The football coach, who had attended Southern Methodist University, steered Bloom there for college. In college, Bloom studied German literature while completing the prerequisites for medical school, and he also married his high school sweetheart; they would have two children together.

After earning admission to Washington University’s medical school, Bloom spent his summers in the lab of physiology professor Gordon Schoepfle. Entering the lab one day, Bloom came upon the axon test chamber once used by Joseph Erlanger and Herbert Gasser, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1944 for recording activity in neurons. This left him “awestruck,” Bloom later wrote in “The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography, Volume 7.”

But it wasn’t until 1962 at St. Elizabeths that Bloom began his journey into neuropharmacology, studying the actions of norepinephrine in the cat hypothalamus and its pharmacology in the rabbit olfactory bulb. At the time, the hypothesis of depression was that it arose from a deficiency of norepinephrine. Supporting this hypothesis meant establishing that norepinephrine was a neurotransmitter.

In his research, Bloom had made it his mission to visualize synapses containing norepinephrine. He moved to New Haven in 1964 after winning a National Institute of Mental Health special fellowship at Yale University to train in electron microscopy and histochemistry, and then took an assistant professor and later an associate professor position at Yale, with norepinephrine never far from his mind. It was during this time that he, Jack Cooper and Robert Roth wrote the quintessential text “The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology.”

A

fter his stint at Yale, Bloom returned to St. Elizabeths in 1968 and opened a lab. He worked with Barry Hoffer and George Siggins, and within a few months identified the Purkinje cell as norepinephrine’s synaptic target in the cerebellar cortex. Bloom also chemically labeled the transmitter characteristics of neurons in each circuit, helping establish that signaling in the brain was both chemical and electrical, and determined that cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) replicated the effects of norepinephrine. This work was “seminal,” says Gary Aston-Jones, director of the Rutgers Brain Health Institute and a former Ph.D. student and postdoctoral researcher in Bloom’s lab.In 1975, Bloom switched coasts and opened a lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, where he studied the role of endogenous opioids and the effects of the amino acid fragment beta-endorphin, helping establish endorphins as neurotransmitters.

Morrison, of Bloom’s lab at the Salk Institute, described the place as an “international hall of fame,” where the great names of science came to collaborate, including molecular biologist Francis Crick and neuroscientists Walle Nauta and Paul Greengard.

Bloom’s first marriage had ended by this time, and in 1980, he married Jody Corey, a University of California, San Diego neurologist. Later, at the Scripps Research Institute, he helped create maps of the monoamine system in nonhuman primates, assisted in the discovery of hypocretins, participated in the NIH Human Brain Mapping project and used mRNA cloning to identify brain-specific proteins. He also co-founded Neurome, Inc., a now-defunct biotechnology company focused on neurodegenerative diseases.

“He played a really major role in moving neuroscience into its modern form, where many different disciplines are applied to studying the brain,” says Steve Foote, former director of the Division of Neuroscience and Basic Behavioral Science at the National Institute of Mental Health, and a postdoctoral fellow in Bloom’s lab.

B

loom was an engaging speaker, Aston-Jones says. A well-known lecture of his (and subsequent book chapter) was titled “The Gains in Brain are Mainly in the Stain.” He was also an instructive mentor, Aston-Jones adds, nudging his students to continue their scientific pursuits. When faced with data, he gave back questions. “Now that you know that, what do you know?” he would ask, and also, “What is the thesis of your thesis?” It seemed that if a colleague brought results to his office, they would leave with “another year’s worth of work,” Morrison says.Still, the inquisitions had a nurturing effect, Morrison adds. “He was more than a mentor. When I first started my own lab in New York, I was constantly asking myself, ‘Well, what would Floyd do?’”

Bloom was elected into the National Academy of Sciences in 1977. In the last leg of his career, he again turned to communication. He served as editor-in-chief of Science from 1995 to 2000.

In the fall of 2018, Bloom had what is thought to be his second stroke, this one debilitating enough that it affected his ability to communicate. To see Bloom “robbed” of language was “a very, very cruel thing,” Aston-Jones says. But readers will still find his voice in “The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology.” The book is now in its 8th edition, still introducing new generations to the concepts of neuroscience.

Charles Chavkin, professor of pharmacology at the University of Washington and a former postdoctoral fellow in Bloom’s lab, read the book out of interest when he was an undergraduate student at Cornell University, and it was what made him want to become a neuropharmacologist. Bloom “was an amazingly articulate individual, incredibly gifted writer,” Chavkin says. “And he articulated a vision that, as an undergraduate, I felt was really very, very compelling.”