A study on the peripheral nervous system’s role in breast cancer has been retracted after one of the authors was found to have fabricated data.

The study’s first author, Atsunori Kamiya of Okayama University, used multiple tumors within one mouse as a group but “failed to describe this situation and in the figure legends stated that n = mice in each group,” according to the retraction notice. Subsequent institutional probes “concluded that the calculated numbers of animals necessary for all experiments were more than the purchased number of animals.” The researchers also failed to obtain appropriate ethics approval for the use of human specimens in the study, the notice continues.

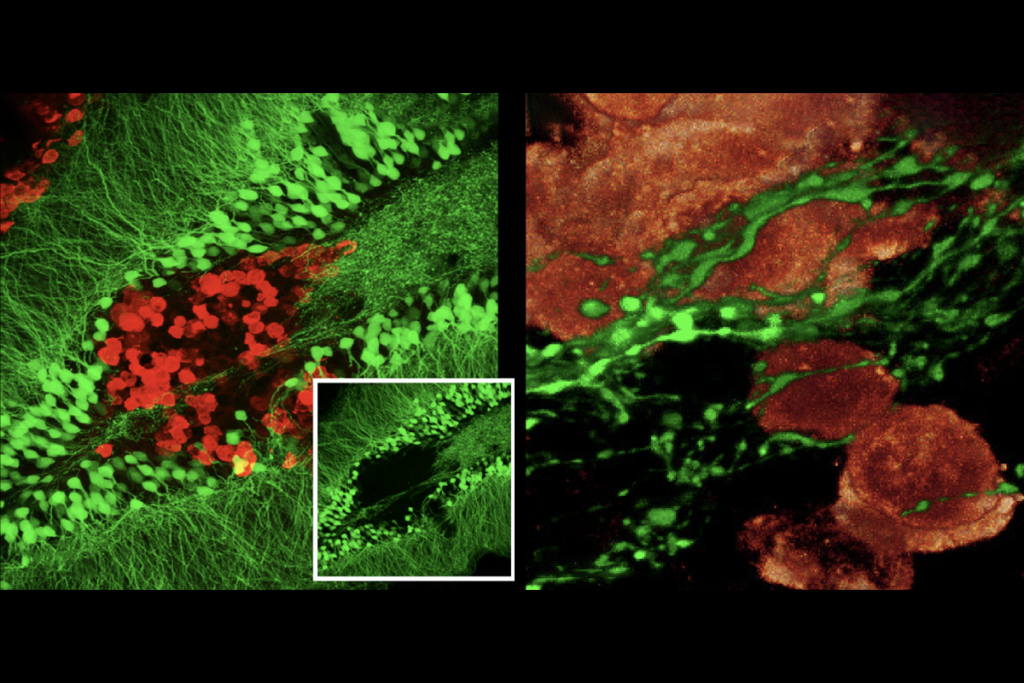

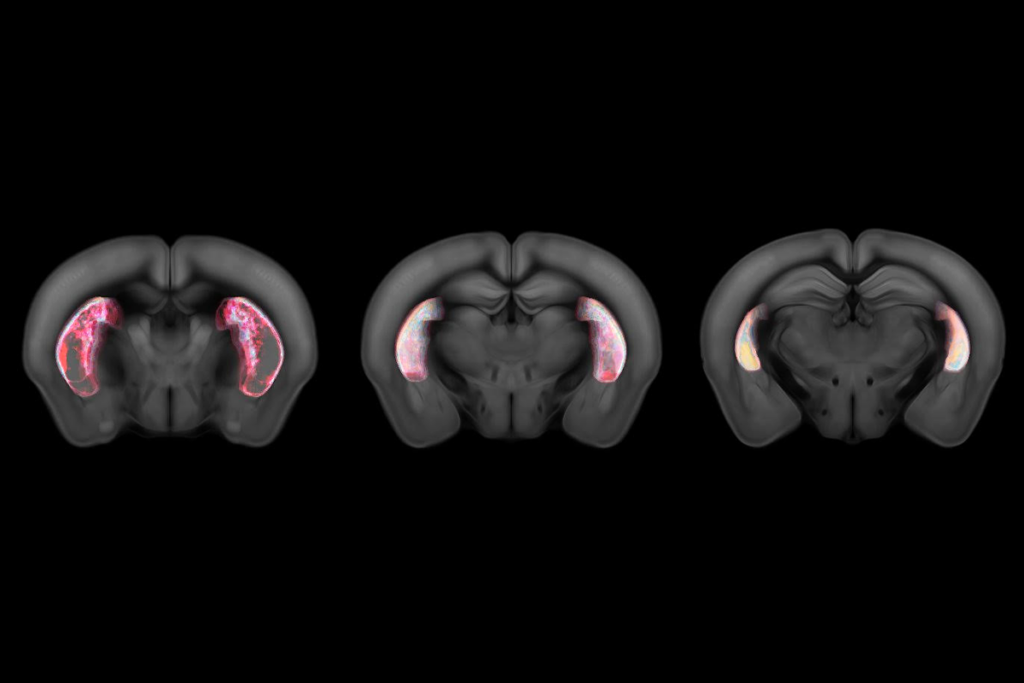

The study, originally published in 2019 in Nature Neuroscience, suggested that activating sympathetic nerves in breast tumors could boost cancer growth and progression, and that inhibiting these nerves had anti-tumor effects—an idea others have studied. The study has been cited 200 times, according to Clarivate’s Web of Science.

“To my eye, the results seemed quite consistent with what was known already in the field, but this study seemed very rigorous and well designed, so it carried a good amount of weight,” says Jeremy Borniger, assistant professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s Cancer Center, who was not involved with the retracted study. “I was surprised about the retraction because the results of this work have largely been corroborated, at least in smaller stories and pieces.”

The study was first flagged in March 2021 on the post-publication peer review site PubPeer, where an anonymous commenter pointed out that there are “very many repeats of statistical errors.”

An investigation by Okayama University and Japan’s National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center Research Institute found 113 instances of fabrication in the study, as well as issues with several of its images, Retraction Watch reported in April 2023. (A co-founder of Retraction Watch, Ivan Oransky, is also editor-in-chief of The Transmitter.) The report said Kamiya was involved in misconduct, and it recommended the study be retracted.

In his defense, Kamiya told the investigative committees that the data underlying the study were unavailable because the hard drive that had stored them was destroyed during the North Osaka Earthquake in 2018, according to the investigative report. Kamiya did not respond to The Transmitter’s email request for comment.

It’s “very surprising” that the study authors couldn’t provide details about the experiments, raw data, primary data and original drawings, says Sarah-Maria Fendt, professor of oncology at KU Leuven, because some funders require all data to be stored for at least five years. Her own institution requires data to be stored for 10 years, Fendt notes.

Kamiya and five co-authors of the study agree to the study’s retraction, the retraction notice states. According to Retraction Watch, the probe also looked into two other studies co-authored by Kamiya but found no evidence of misconduct.

Borniger says he was surprised by the comprehensiveness of the original study, which contained more than 30 supplementary figures. “It is an enormous study that must have taken several years to complete,” he says. “Now that it is retracted, I can see that this is in part due to pseudo-replication, where individual tumors were treated as individual mice, leading to artificially high statistical power and spurious results.”

Borniger, whose team is following up on the research reported in the now-retracted study, says the retraction means his team has to first validate the original findings before proceeding with their studies. “This means that we are switching our focus from metastatic disease to the primary tumor, setting us back significantly.”

“It is disappointing,” Borniger says. “Regardless, I don’t think this retraction will have a large effect on the field going forward, as there are now many groups working on autonomic control of tumor growth, and the general conclusions of this work seem to be holding up.”