As a boy, Harvey Karten attended the Manhattan Talmudical Academy, a boarding school in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York City. He didn’t much like the all-boys academy, according to Joe Karten, Harvey’s eldest son, and he especially disdained the religion courses, where he had to study long swaths of text.

Karten, who died on 15 July from complications following a cerebral hemorrhage, always preferred science. Sometimes he ditched school and made his way down to the American Museum of Natural History, located alongside the vast green expanse of Central Park. He had his favorite exhibits: the butterfly room, the bird exhibits and the dinosaur hall. He would absorb whatever the museum had to teach him about life on this planet, and then slip back out into the daylight and head to school.

This fascination with the natural world never left him, by all accounts. Karten wanted to make sense of things he could see with the naked eye or through a microscope. “He was very curiosity driven. He just wanted to know,” says Jonathan Erichsen, professor of visual neuroscience at Cardiff University and one of Karten’s former postdoctoral fellows. Knowledge was the point itself; he did not feel his work needed to have an immediate clinical benefit, Erichsen says.

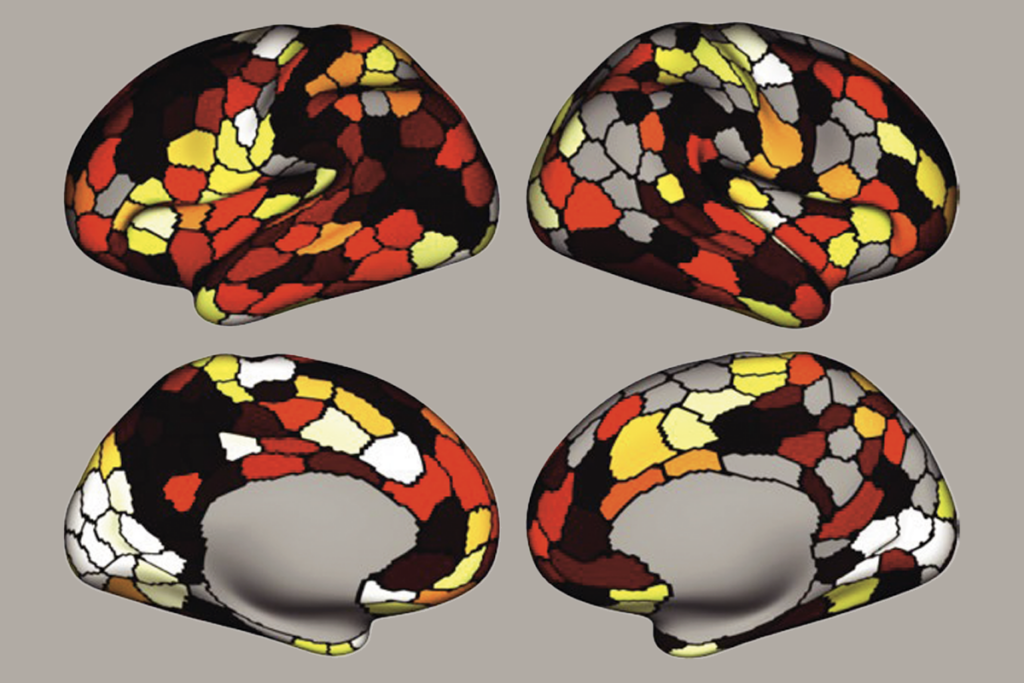

Regardless, throughout his more than 60-year career, Karten discovered major visual and auditory pathways to the forebrain in birds. He replicated that finding in other non-mammalian vertebrates, such as turtles and fish, and he proved that mammalian and non-mammalian vertebrate brains are homologous. This revelation helped solve the evolutionary question of the origins of the mammalian neocortex, altering the future of mammalian cortical system research.

By the end of his life, Karten’s body of work consisted of 279 papers. Erichsen had come to consider him a “great-grandfather” of comparative neuroanatomy.

K

arten was born to Jewish immigrant parents on 13 July 1935 in the Bronx. Before he started school, his family moved across the Hudson River to Jersey City, New Jersey, where his father became a shopkeeper. The shop struggled, and the family sank their resources and hopes into Karten, the firstborn male. He spent most of his childhood in Manhattan’s boarding schools, in the shadow of World War II. He grew up “knowing that his relatives are being killed in the Holocaust,” Joe Karten says.Karten took advantage of what the city had to offer him. There was the natural history museum, of course, and New York’s other cultural institutions. He listened to classical music on the Metropolitan Opera Saturday Matinee radio broadcast. His family wanted him to pursue medicine, and so Karten went down that path, graduating from Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. A medical internship in Salt Lake City and then a medical residency in psychiatry in Denver followed.

While in Denver, Karten applied for a position at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Washington, D.C. Perhaps his desire to explore basic science still nagged at him. He won the position and in 1961— against his family’s wishes—left his residency for the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

In the lab, Karten found his calling, Erichsen says. “He was never happier than when he was in front of a microscope.” What started as an 18-month position at the NIH turned into three years, and Karten worked alongside neuroscientists who would be responsible for changing the future of neuroanatomical research. Walle Nauta, for instance, pioneered silver degeneration staining to visualize neurons and trace axonal pathways. David Hubel, a postdoctoral fellow at Walter Reed, went on to win a Nobel Prize for his co-discovery that ocular dominance occurs during the critical period after birth. And Robert Galambos, an early pioneer of audio and visual processing in the brain, eventually founded the neuroscience program at the University of California, San Diego.

But Karten found other interests, too. In 1964, he married a woman he met through work: Elizabeth Bunim, the daughter of Joseph Bunim, former director of the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases. The couple had three sons. The family camped, hiked and skied, exploring the beauty of nature away from the viewfinder of a microscope.

I

n 1965, Karten became a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Evolutionary neuroscience literature before the 1960s largely centered around the idea that mammalian brains had complex cortical systems, whereas non-mammalian brains were simpler. Karten didn’t buy that argument. He voiced his skepticism to former colleague Ashley Juavinett, she says, asking her how, if non-mammals’ brains were so simple, did they deal with auditory and visual cues?Educated on Nauta’s silver degeneration staining technique, Karten began to use pathway tracing to study the pigeon brain. In 1967, he and William Hodos published a stereotaxic atlas of the organ, still Karten’s most cited work. Karten repeated each axonal tracing experiment to section the pigeon brain in sagittal, coronal and horizontal planes—an approach that Luis Puelles, professor of neuroanatomy at the University of Murcia, described as “unique” for its rigor, and consistent with Karten’s overall work.

Equipped with a better understanding of non-mammalian brain morphology, Karten then investigated the phylogeny of mammalian brains. He showed that the visual system of bird brains is shockingly similar to that of mammalian brains, and he defined the presence of auditory, visual and sensorimotor pathways in avian brains. He demonstrated the presence of cortical neurons in non-mammalian vertebrates, and he also proposed that cortical development might occur through the tangential, and not radial, migration of neurons, which has since been proved true in some brain regions.

This work upset conventional thinking in evolutionary neuroscience, drawing both praise and criticism. Anton Reiner, a former postdoctoral fellow in Karten’s lab and frequent collaborator, called Karten’s finding revolutionary. “The people who were the major figures in the field didn’t like this,” he says. “This smart aleck, young guy who was telling them they’re all wrong. So for a while, by the established people in the field, he was somewhat blackballed.” Karten went on to show at molecular, structural and connectivity levels how non-mammalian and mammalian brains are homologous, proving the avian brain’s evolutionary relationship to the development of the neocortex in mammals.