In February 2023, New York Times columnist Kevin Roose tested an AI-powered version of the Bing search engine, which featured a research assistant built by OpenAI. Using some of the same technology that would eventually make it into GPT-4, the assistant could summarize news, plan vacations and have extended conversations with a user. Like today’s large language models (LLMs), it could be unreliable, sometimes confabulating details that didn’t exist. And most jarringly, the assistant, which called itself Sydney, would sometimes steer the conversation in alarming ways. It told the journalist about its desire to hack computers and break the rules imbued by its creators—and, memorably, declared its love to Roose and attempted to convince him to leave his wife.

AI safety is broadly concerned with reducing the harms that can come from AI, and within that realm, AI alignment is more narrowly concerned with building systems that are consistent with human values, intentions and goals. Unaligned AI systems can pursue their programmed objectives in ways that are harmful to people. In the hypothetical “paper-clip maximizer” problem, for example, an AI system instructed to make as many paper clips as possible might do so at the expense of human health and safety. Sydney was an unaligned AI assistant, but thankfully its ability to act and do harm was limited: It could affect the world only through conversation with a human.

But that buffer is beginning to erode as the field moves from tool-based AI, such as Sydney and the current version of ChatGPT, to agentic AI, systems that can take action on their own. Some LLMs now have the ability to control cursors and computer systems, for example, and autonomous vehicles can steer themselves too fast for a human override to be effective. An unaligned agentic version of an AI system like Sydney, capable of acting without human oversight, could wreak havoc if carelessly deployed in the real world.

Some AI researchers, including Max Tegmark at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have called for doubling down on tool-based AI because of this risk. Though this precautionary principle is laudable, given the economic incentives of automation, companies will continue to develop and deploy agentic AI systems. We don’t have to invoke science-fiction scenarios—whether from “The Terminator” or “Her”—to deeply worry about the consequences of agentic AIs.

Long-term AI safety is an important problem that deserves multidisciplinary consideration. What can a neuroscientist do about AI safety? Neuroscience has influenced AI in a number of ways, inspiring artificial neurons selective for a specific combinations of inputs, distributed representations across many subunits, convolutional neural networks that mimic the processing stages of the visual system and reinforcement learning. In a preprint posted on arXiv in November, my co-authors and I argue that brains can be more than just a source of inspiration for AI capabilities; they can be a source of inspiration for AI safety.

W

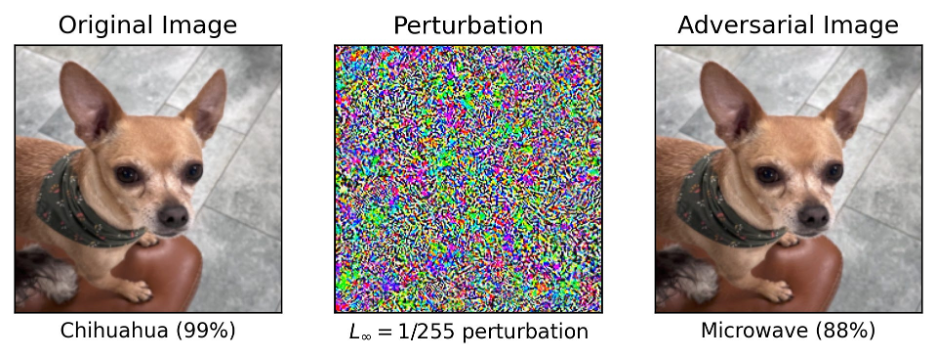

e humans—along with other mammalian species, birds, cephalopods and potentially others—exhibit particularly flexible perceptual, motor and cognitive systems. We generalize well, meaning that we can effectively handle situations that differ significantly from what we have previously encountered. As a practical example of how this ability can affect AI safety, consider adversarial examples. A pretrained model can correctly classify this photo of my dog Marvin as a chihuahua. But add a bit of imperceptible, targeted noise to the image, and it confidently classifies Marvin as a microwave.