It is often said that the brain is the most complex object in the universe. Whether this cliche is actually true or not, it points to an undeniable reality: Neural data is incredibly complex and difficult to analyze. Neural activity is context-dependent and dynamic—the result of a lifetime of multisensory interactions and learning. It is nonlinear and stochastic—thanks to the nature of synaptic transmission and dendritic processing. It is high-dimensional—emerging from many neurons spanning different brain regions. And it is diverse—being recorded from many different species, circuits and experimental tasks.

The practical result of this complexity is that analyses performed on data recorded from specific, highly controlled experimental settings are unlikely to generalize. When training on data from a dynamic, nonlinear, stochastic, high-dimensional system such as the brain, the chances for a failure in generalization multiply because it is actually impossible to control all of the potentially relevant variables in the context of controlled experimental settings. Moreover, as the field moves toward more naturalistic behaviors and stimuli, we effectively increase the dimensionality of the system we are analyzing.

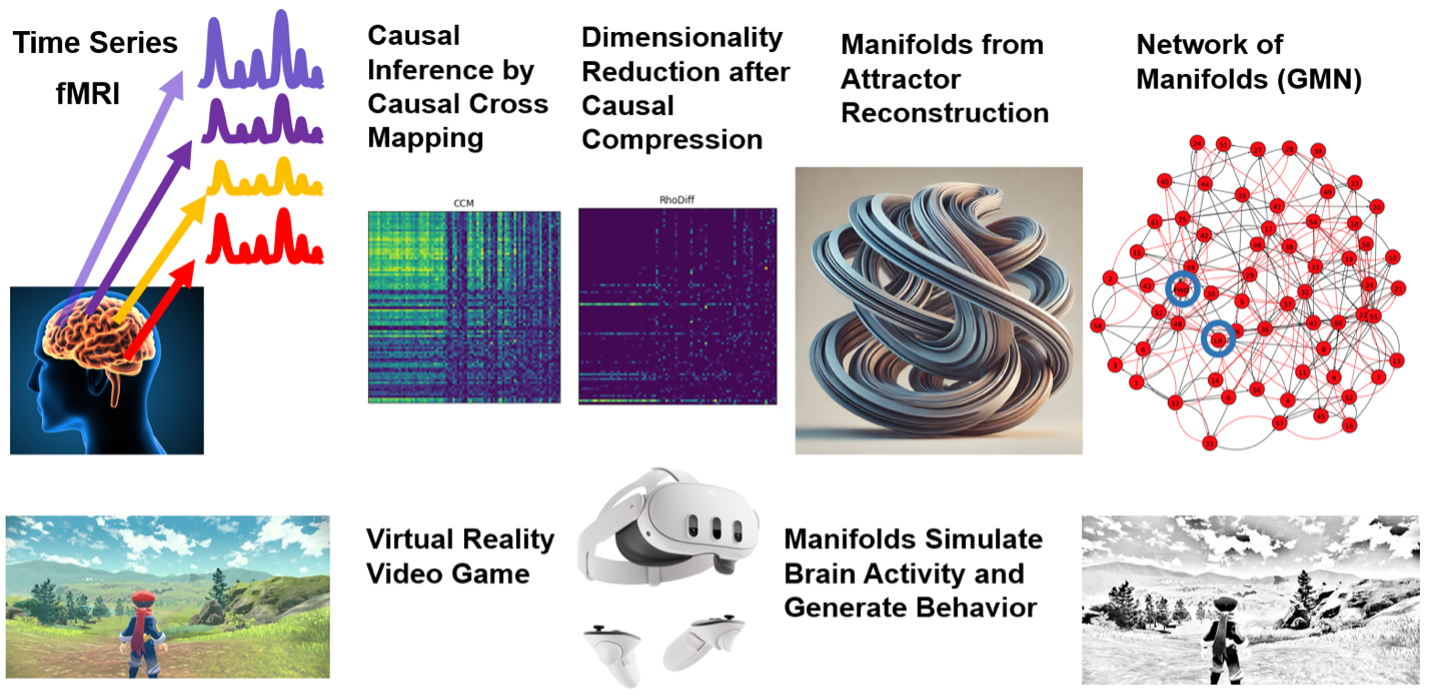

How can we make progress, then, in developing a general model of neural computation rather than a series of disjointed models tied to specific experimental circumstances? We believe that the key is to embrace the complexity of neural data rather than attempting to sidestep it. To do this, neural data needs to be analyzed by artificial intelligence (AI).

AI has already demonstrated its immense utility in analyzing and modeling complex, nonlinear data. The 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for example, went to AI researchers whose models helped us to finally crack the problem of predicting protein folding—a similarly complex analysis task on which traditional modeling techniques had failed to make significant headway. AI has helped researchers make progress on many other devilishly complex analysis problems, including genomics, climate science and epidemiology. Given the initial results in neuroscience, it seems likely that AI will help our field with its challenging analyses as well.

To effectively adopt AI for neural data analysis, though, we must accept “the bitter lesson,” an idea first articulated by AI researcher Rich Sutton, a pioneer of reinforcement learning. In a 2019 blog post, Sutton observed that the most successful approaches in AI have been those that are sufficiently general such that they “continue to scale with increased computation.” In other words, clever, bespoke solutions engineered to tackle specific problems tend to lose out to general-purpose solutions that can be deployed at a massive scale of internet-sized data (trillions of data points) and brain-sized artificial neural networks (trillions of model parameters or “synaptic weights”). Sutton suggested we need to recognize that “the actual contents of minds are tremendously, irredeemably complex; we should stop trying to find simple ways to think about the contents of minds, such as simple ways to think about space, objects, multiple agents, or symmetries.” In other words, embrace complexity.

We believe that the bitter lesson surely applies to neural data analysis as well. First, there is no reason we can see to think that neural data would somehow be an exception to the general trend observed across domains in AI. Indeed, evidence to date suggests it is not. Second, neural data is a clear candidate for the benefits of scale, precisely because it is so complex. If we are to embrace the complexity of neural data—and generalize to novel situations—then we must move toward a data-driven regime in which we employ large models trained on vast amounts of data. Indeed, there is an argument to be made that our inability to extract meaningful signals from complex neural data has held back progress on practical applications of neuroscience research. AI models trained at scale on this data could potentially unlock numerous downstream applications that we have yet to even fully envision.

H

ow do we unlock the full complexity of brain data and scale up our understanding of the mind? First, we need models that can make sense of multimodal datasets combining electrophysiology, imaging and behavior across different individuals, tasks and even species. Second, we need infrastructure and computational resources to power this transformation. Just as AI breakthroughs were fueled by high-performance computing, neuroscience must invest in infrastructure that can handle the training and fine-tuning of large generalist models. Finally, scaling demands data—lots of it. We need large, high-quality datasets spanning species, brain regions and experimental conditions. That means capturing brain dynamics in natural, uncontrolled environments to fully reflect the richness and variability of brain function. By combining these three ingredients—models, computing and data—we can scale up neuroscience and uncover the principles that underlie brain function.Thanks to initiatives such as the International Brain Laboratory, the Allen Institute and the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s BRAIN Initiative, we are beginning to see the power of large-scale datasets and open data repositories, such as DANDI. These efforts are building the foundation for the construction of a unified model and driving the development of data standards that make sharing and scaling possible.

But we are not there yet. Too much data remains trapped on hard drives, hidden away in individual labs, never to be shared or explored beyond its original purpose. Too many models remain small-scale and boutique. To overcome this, we need a shift—a new culture of collaboration backed by incentive structures that reward data-sharing and its transformative potential. We believe that the promise of large-scale AI models for neural analysis could become the spark that motivates change. We arrive, therefore, at a call to action. The field must come together to create:

Robust global data archives: We need to continue to expand shared, open-access repositories, where neural data from around the world can be pooled, standardized and scaled. By doing so, we can supercharge the development of powerful AI tools for understanding brain function, predicting brain states and decoding behavior. This is more than a call for data-sharing—it’s a call to shape the future of neuroscience. But it also requires funding; we need to determine who will pay for the storage and curation of these large-scale archives.

Large-scale computing resources dedicated to training AI models on neural data: Training AI models at scale involves the use of significant computational resources. The number of GPU hours required to train an artificial neural network with billions or trillions of synaptic connections on trillions of data points is prohibitive for any individual academic laboratory, or even institute. In the same way that other scientific communities, such as astronomers, pool resources for large-scale efforts, neuroscientists will need to figure out how to band together to create the computational resources needed for the task before us.

Professional software developers and data scientists: Saving, standardizing, preprocessing and analyzing data comes at a huge cost for most neuroscience labs. They may not have staff in their own labs with the technical background or time to do it. Many neuroscience labs also are constantly streaming in new data—how do you know which data to prioritize and process for such efforts? And building a large-scale neural network requires a team of dedicated engineers who know how to work together, not a collection of graduate students with their own bespoke data-processing scripts. We need dedicated engineers and staff who can help streamline data standardization and storage, and help to build AI models at scale.

Altogether, large-scale models trained on diverse data could enable cross-species generalization, helping us understand conserved principles of brain function. They could also facilitate cross-task learning, enabling researchers to predict how neural circuits respond in novel contexts. Applications extend beyond basic science to clinical and commercial domains, where scaled models could improve brain-computer interfaces, mental-health monitoring and personalized treatments for neurological disorders.

We believe that these benefits are worth the price of thinking about new mechanisms and strategies for doing collective neuroscience at scale. But researchers disagree on how best to pursue a large-scale AI approach for neural data and on what insights it might yield. Unlike protein folding, assembling the data will require a network of ostensibly independent researchers to come together and work toward a shared vision. To get diverse perspectives from across the field, we asked nine experts on computational neuroscience and neural data analysis to weigh in on the following questions.

1. What could large-scale AI do for neuroscience?

2. What are the barriers that prevent us from pursuing an AlphaFold for the brain?

3. What are the limits of scale, and where will we need more tailored solutions?