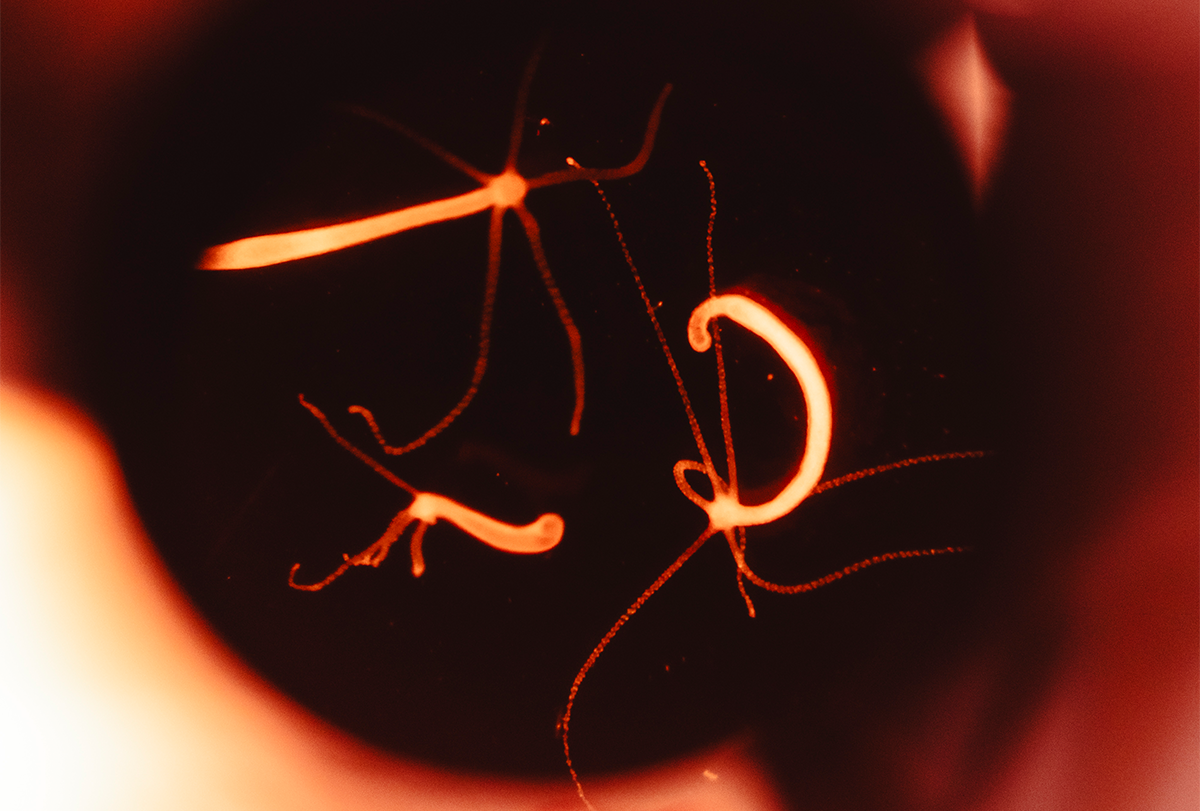

After speaking with Brenner, Yuste asked his graduate student Christophe Dupre to look into Hydra. Dupre went to the University of California, Irvine to visit Robert Steele, who had been studying Hydra since the 1980s. The first transgenic Hydra was created in 2006, by Thomas Bosch and his collaborators. Yuste and Dupre wanted to build on that (and on critical work done in Steele’s lab) and make the animal more useful for neuroscience. They created a transgenic line that expresses a calcium indicator called GCaMP6s in neurons. The idea was to allow researchers to see “the activity of every neuron in an animal during behavior,” Yuste says.

Dupre went back to Irvine to show Steele details on the transgenic Hydra. He pulled up a video of the animal on his laptop, its neurons flashing away. “My jaw dropped,” Steele says. “This is the kind of thing you thought we would just be dreaming about forever, and here it was reality.” Yuste and Dupre published the work in Current Biology in 2017. The editors put it on the cover.

F

or more than 135 years, biologists and neuroscientists have gathered at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, to study and exchange ideas. Less than a mile’s walk from the lab, and alongside the Church of the Messiah, is the Woods Hole Village Cemetery. Nobel Prize winner

Albert Szent-Györgyi is buried there, and so are parthenogenesis researcher

Jacques Loeb and Nobel winner

Otto Loewi, among many other scientists. Yuste was invited to lecture on

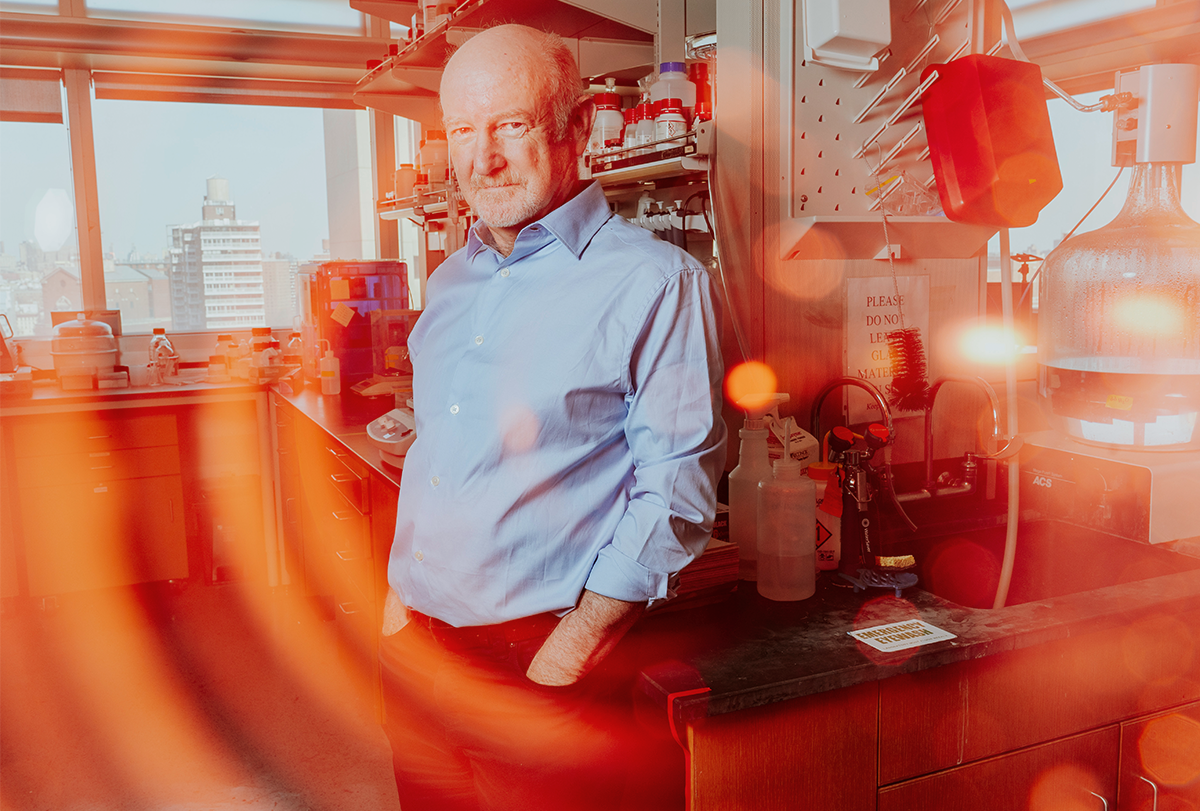

Hydra at MBL in 2014, and he returned the next year to teach a summer course. In 2017, his third year teaching the course, he packed equipment and an incubator into his car and relocated his lab and team to MBL for the summer.

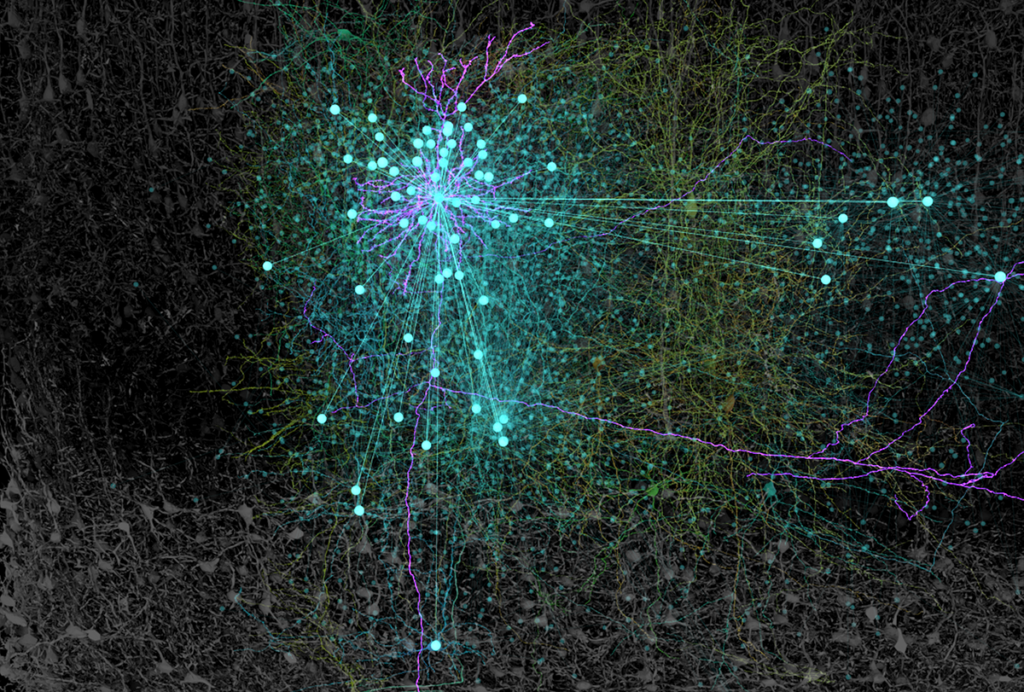

The lab became a “watering hole” for Hydra researchers in the United States, at the time only enough people to fit at a “full picnic table,” Yuste says. Steele came to Woods Hole. So did Adrienne Fairhall, professor of physiology and biophysics at the University of Washington. Eventually, Yuste and Fairhall, with others, would create an algorithm to track the position of a neuron using calcium imaging in freely behaving animals, with Hydra as the test case. Today there are about 10 different labs looking at Hydra, totaling roughly 40 researchers, Yuste says.

Yuste’s work on the animal has expanded as much as the field. He never had much interest in peptides, but while Yuste and his postdoc Wataru Yamamoto were studying somersaulting in Hydras—curious as to “how the hell does this nervous system with 300 neurons” achieve such complex behavior, Yuste says—they discovered that rhythmic potential neurons are activated by a neuropeptide called Hym-248 before the somersaulting begins. Now Yuste believes neuroscience has “underestimated the importance of chemical signaling.”

That “how the hell” kind of inquisition is a hallmark of Yuste’s, as is his enthusiasm. Fairhall says Yuste is “one of the more complex people I know in neuroscience,” pointing to his “brilliance” and a reputation for “creativity and innovation,” but also saying he can be demanding and “a bit irascible.”

Yuste is aware of this. Partly it’s in his nature to be “frank,” he says, but he trained in medicine and saw that doctors sometimes need to deliver woeful news without sugarcoating, and he employs the same style with his students. But beyond that, “the worst thing” a principal investigator can do to a trainee is avoid pointing out mistakes, he says, “because that will hurt his or her career.”