New footage documents microglia pruning synapses at high resolution and in real time. The recordings, published in January, add a new twist to a convoluted debate about the range of these cells’ responsibilities.

Microglia are the brain’s resident immune cells. For about a decade, some have also credited them with pruning excess synaptic connections during early brain development. But that idea was based on static images showing debris from destroyed synapses within the cells—which left open the possibility that microglia clean up after neurons do the actual pruning.

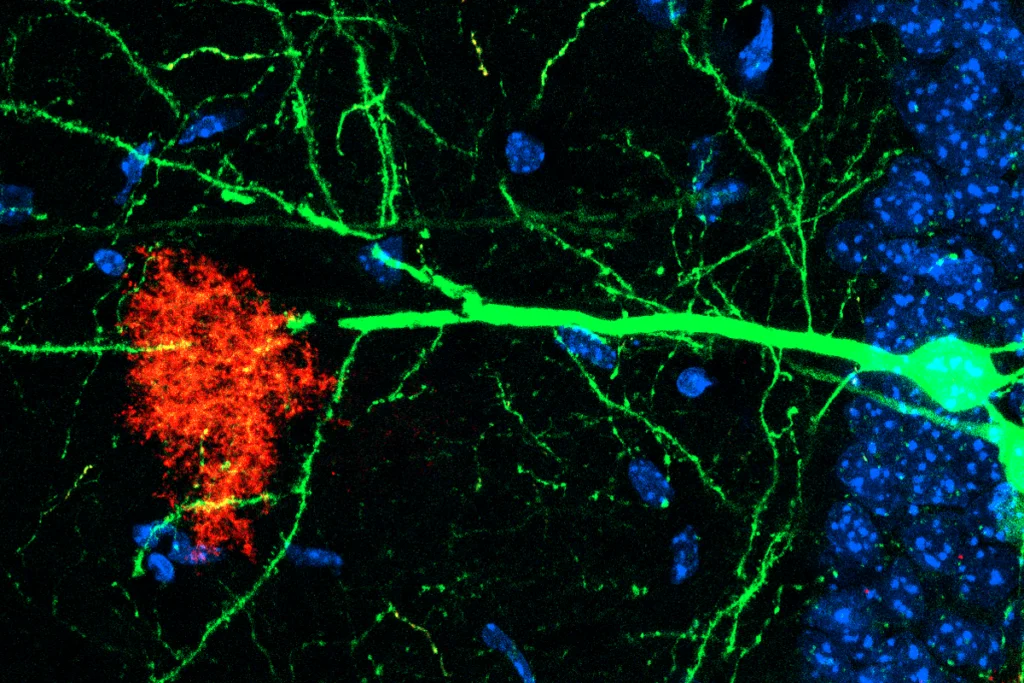

In the January movies, though, a microglia cell expressing a green fluorescent protein clearly reaches out a ghostly green tentacle to a budding presynapse on a neuron and lifts it away, leaving the neighboring blue axon untouched.

“Their imaging is superb,” says Amanda Sierra, a researcher at the Achucarro Basque Center for Neuroscience, who was not involved in the work. But “one single video, or even two single videos, however beautiful they are, are not sufficient evidence that this is the major mechanism of synapse elimination,” she says.

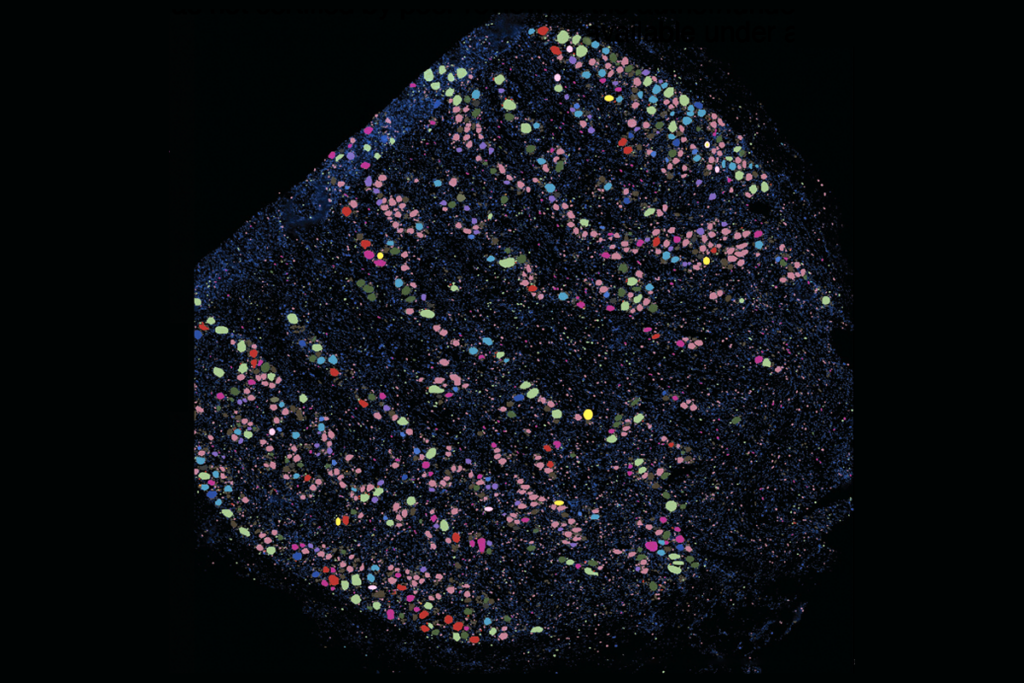

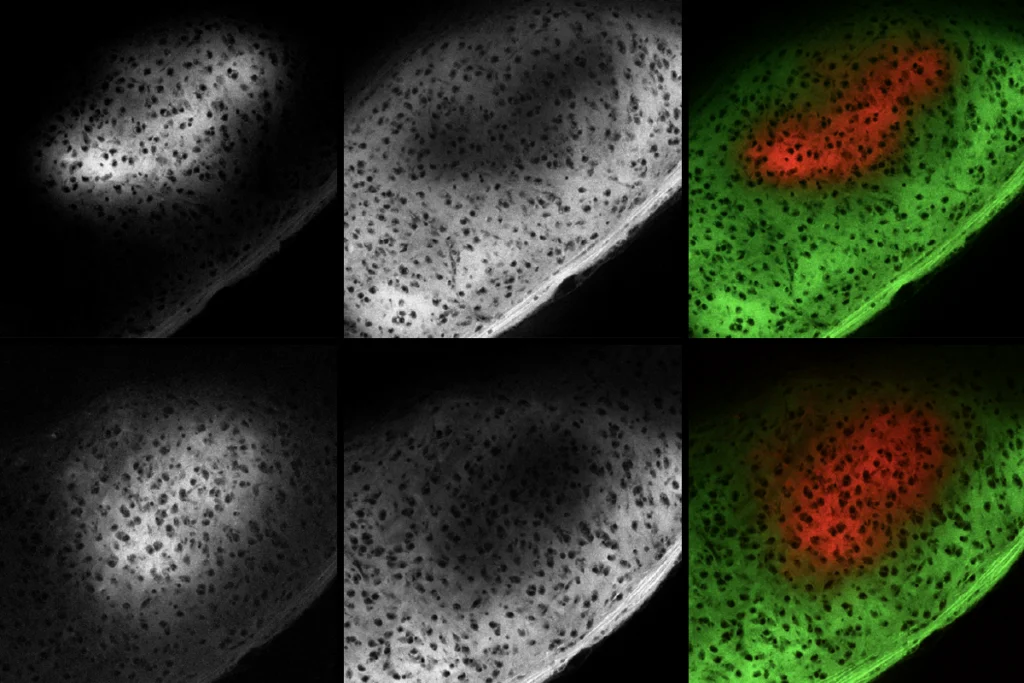

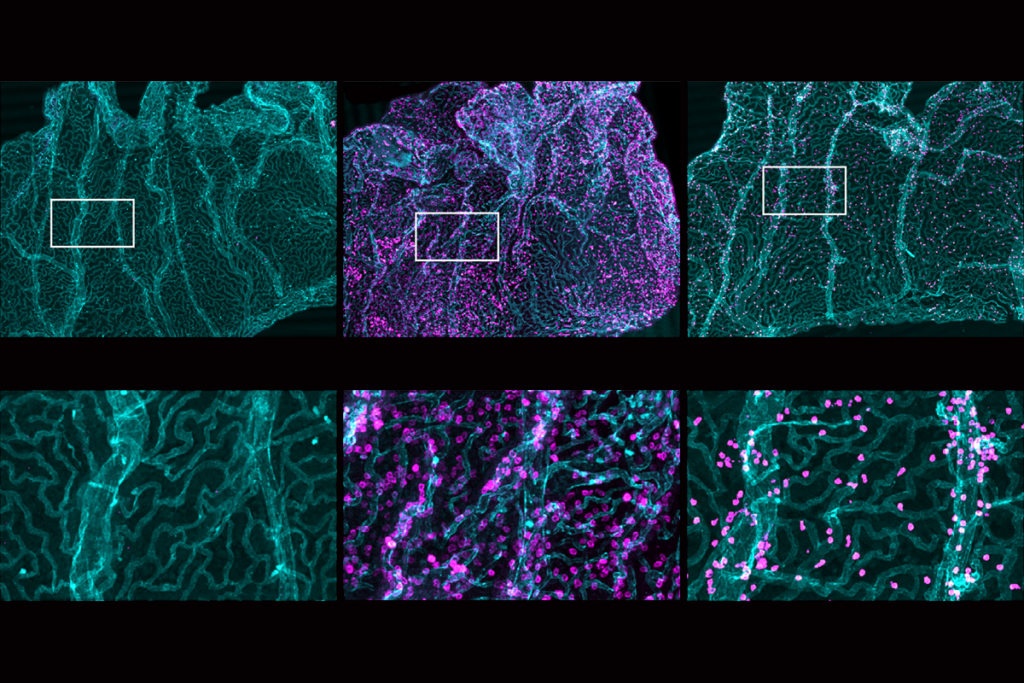

In the new study, researchers isolated microglia and neurons from mice and grew them in culture with astrocytes, labeling the microglia, synapses and axons with different fluorescent dyes. Their approach ensured that the microglia formed ramified processes—thin, branching extensions that don’t form when they are cultured in isolation, says Ryuta Koyama, director of the Department of Translational Neurobiology at Japan’s National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, who led the work. “People now know that ramified processes of microglia are really necessary to pick up synapses,” he says. “In normal culture systems, you can’t find ramified processes. They look amoeboid.”

Two previous studies recorded microglia “nibbling” at synapses, a process called trogocytosis. But Koyama characterizes the action in his recordings as the first live-cell imaging evidence of synaptic phagocytosis, in which microglia engulf their target.

Dori Schafer, associate professor of neurobiology at UMass Chan Medical School, who was one of the first to identify microglia pruning, disputes Koyama’s claim, saying that the new videos show trogocytosis rather than phagocytosis.

The field uses the two terms inconsistently, Koyama says, and so the process he and his colleagues documented could also be called trogocytosis. Previous live-cell imaging did not label axonal membranes, he adds, leaving open the possibility that microglia may have been phagocytosing detached debris rather than intact synapses. Koyama says his team avoided this issue by tagging membranes with a near-infrared fluorescent protein.

Whether the process recorded in the new videos is trogo- or phagocytosis, the evidence is unprecedented, Schafer says. “Ryuta’s imaging is even more clear, and it has a lot more mechanistic detail” than the previous work, she says. For example, Koyama’s team tracked their microglia every minute, compared with only once every six minutes in one of the trogocytosis papers. Further experiments in the new study also suggest that increased neuronal activity prompts the pruning process by activating an enzyme called caspase-3, which initiates a process that tags certain synapses with an “eat-me” signal.