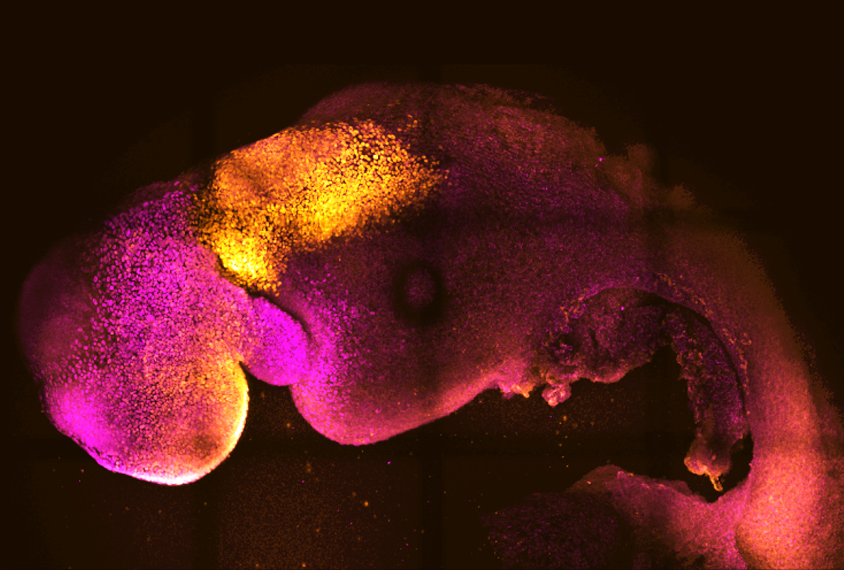

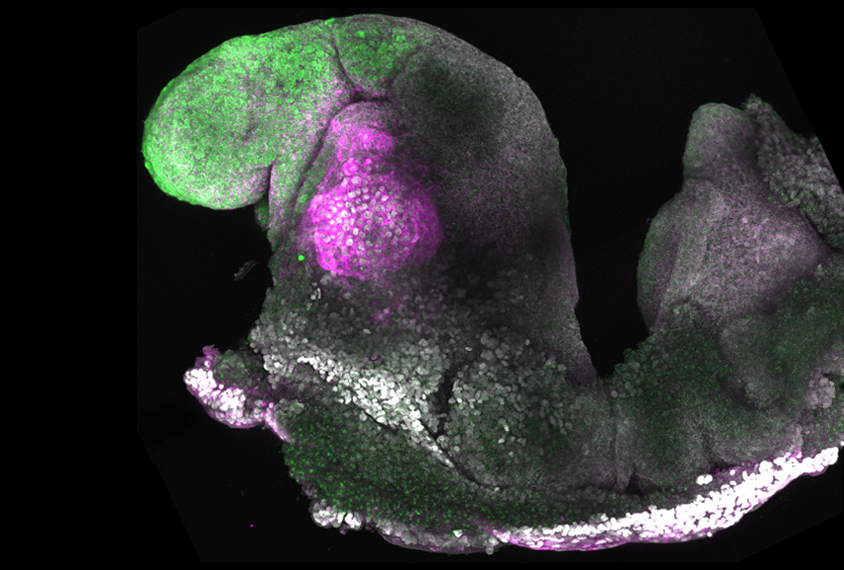

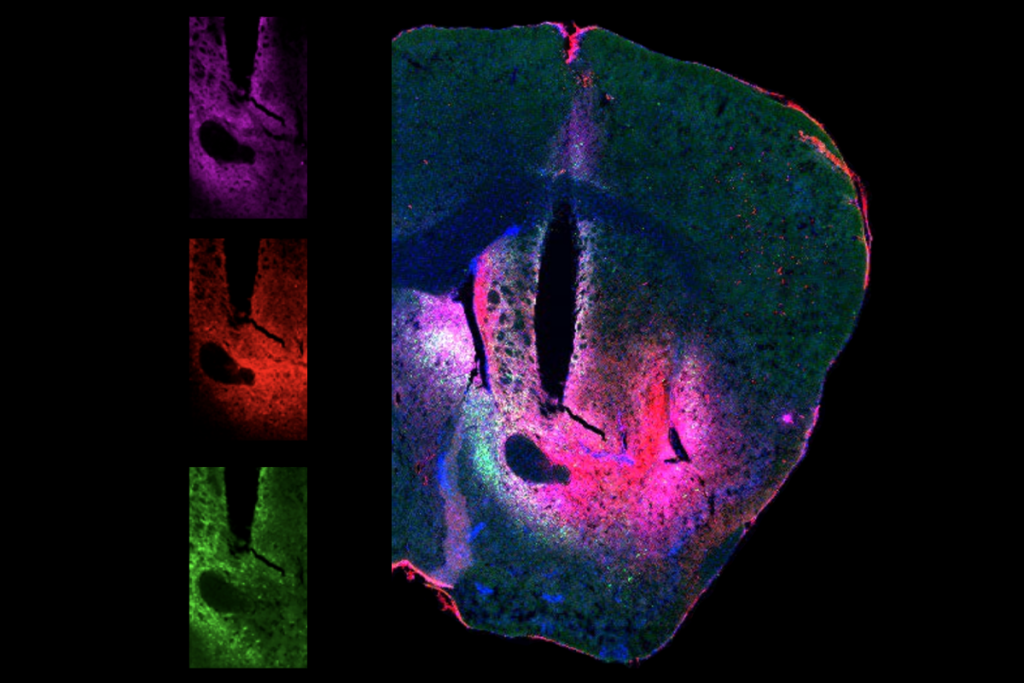

A mix of three mouse stem-cell types can transform into a synthetic embryo — one that develops a budding brain, beating heart and other complex features — in a dish.

Such ‘embryoids’ could help to elucidate the relationship between genes and traits, including how mutations linked to autism affect early development. Two independent teams shared slightly different recipes to create these model systems in Nature in August and in Cell in September, respectively.

Studying mouse embryos made the old-fashioned way can be expensive and slow, with it sometimes taking a year to establish a new mouse line. By contrast, stem cell lines take only a couple of months to make and can give rise to embryoids in just several more days or weeks.

“Creation of embryoids using stem cells is driven by the desire to understand just how much developmental potential these cells have, find ways to replace the animals used in research, increase the speed of research, just to name a few things,” says Gianluca Amadei, a research fellow at the University of Padua in Italy and an investigator on the Nature paper, work he conducted as a postdoctoral fellow in Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz’s lab at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

“I hope that as we develop and refine these systems, it will be faster and faster to test the function of new genes and see whether they play a role in autism,” he says.

The embryoids represent a “great advancement” and offer a more holistic model than organoids to investigate autism, says Alysson Muotri, professor of pediatrics and cellular and molecular medicine at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in either study.

“It would be a dream for people like me who want to study all the tissues, all the mutations,” he says, envisioning introducing an autism-associated mutation in an embryoid and then studying how it manifests across the embryoid’s interconnected tissues.

T

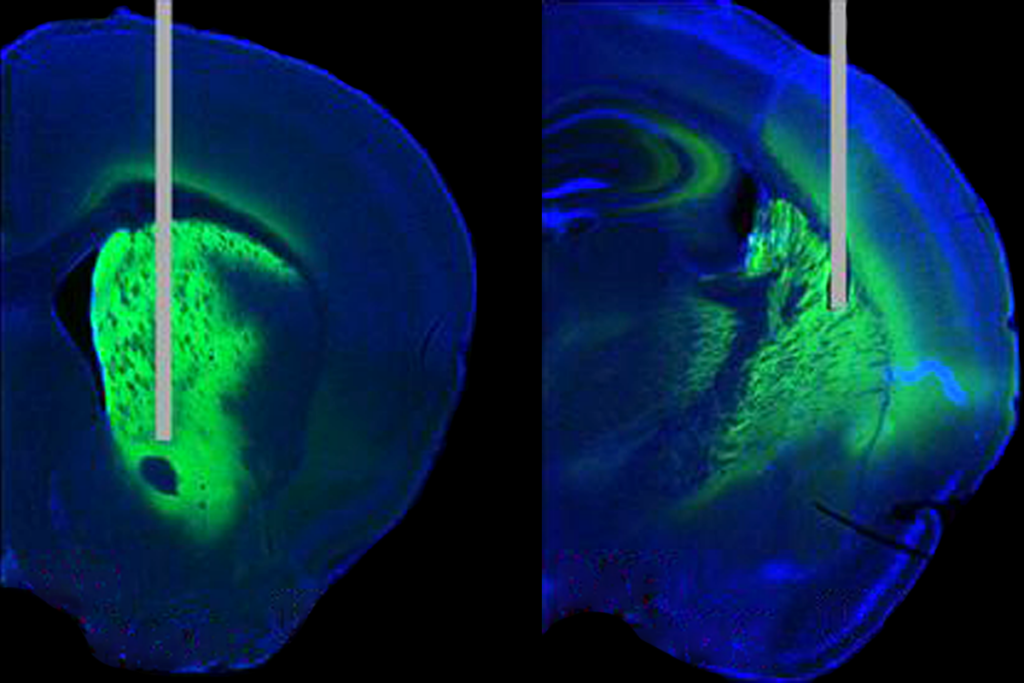

o create the embryoid models, both research groups mixed together three primary ingredients: mouse embryonic stem cells plus two other cell lines that mimic cells involved in the formation of an embryo. The two teams used different techniques to generate one of those two cell lines, but their approaches were otherwise similar.By day three, their mixtures had formed into an ‘egg cylinder’ structure, which the teams continued to culture. After five more days in a rotating chamber, the embryoids had grown to resemble a mouse embryo at mid-gestation.