A team of researchers and citizen scientists has mapped all of the circuits in the entire brain of an adult fruit fly.

The connectome, described in a preprint posted to bioRxiv in June, traces 53 million synapses among nearly 130,000 neurons in Drosophila melanogaster, making it the largest brain map to date. It comes nearly 40 years after researchers finished the first-ever connectome, which mapped all 302 neurons in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans’ nervous system.

“It’s a huge step up from the connectome of C. elegans,” says Donald O’Malley, associate professor of biology at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, who was not involved in the new work. “This is really a big breakthrough.”

should emphasize this is ACTUAL connectivity map of neurons, synapses and thus neural circuits!

.

not to be confused with #fMRI, #DTI “connectomes” which report co-activation between voxels containing 500,000 neurons (4 dros. brains) and/or pathways, fiber bundles between voxels. https://t.co/AvNyt0HsDJ— Donald M. O’Malley (@mazefire56) July 1, 2023

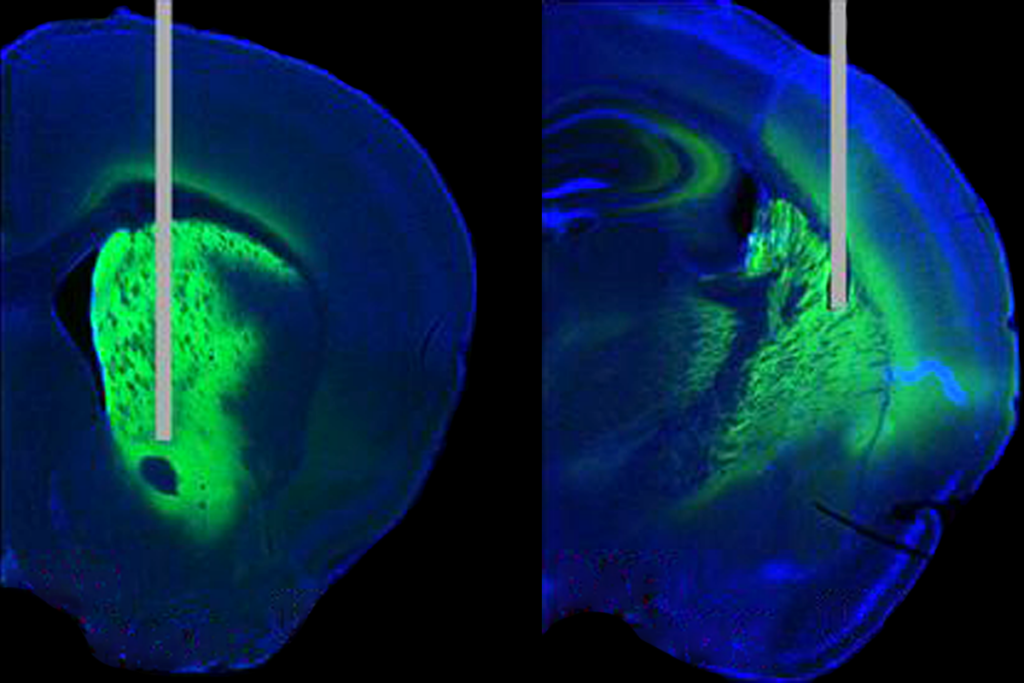

Complete connectomes already exist for the larval sea squirt Ciona intestinalis, the marine worm Platynereis dumerilii and the larval fruit fly; in 2020, researchers unveiled a partial adult fruit fly map, often referred to as the “hemibrain,” consisting of 25,000 neurons in the central brain.

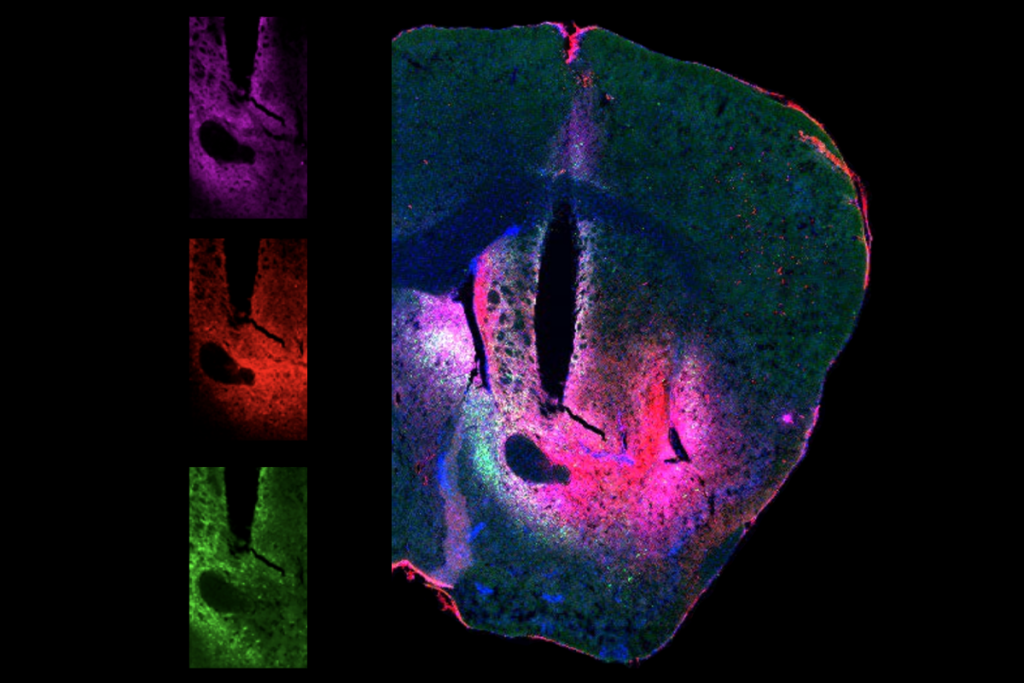

To create the hemibrain, a team led by researchers at the Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Virginia, imaged a portion of the fly brain with electron microscopy, reconstructed the brain via machine learning, and manually reviewed and “proofread” the connections mapped by the computer.

The new connectome is the result of a similar approach carried out by the FlyWire Consortium, which was created in 2019 by Mala Murthy and Sebastian Seung at Princeton University. The consortium involves hundreds of neurobiologists, computer scientists and other contributors around the world.

The consortium’s online platform allows anyone — including citizen scientists — to become trained in the proofreading process and edit the connectome in real time, similar to Wikipedia. Each neuron requires about 19 minutes of proofreading time, according to a 2021 paper describing the platform.

The connectome’s data are publicly available on the Connectome Data Explorer (Codex). Because FlyWire participants also annotated the map, users can search Codex for a range of cell attributes, including brain region, cell type and lineage, and associated neurotransmitters.

Its potential applications are broad, says study investigator Sven Dorkenwald, a graduate student in Seung’s lab. For example, researchers who study particular neurons can pinpoint those neurons’ connections in FlyWire and devise hypotheses about their function that could then be tested in living flies.

“I’m looking forward to seeing what people do and find,” Dorkenwald says. “That’s definitely part of the joy of working on this kind of data.”

T

Nearly 74,000, or 64 percent, of the adult intrinsic neurons are contained within the fly’s vision areas, or optic lobes, compared with about 32,000, or 28 percent, located in the central brain.

“I found that absolutely shocking,” says Michael Winding, group leader at the Francis Crick Institute in London, England, and an investigator on the larval fly connectome, who was not involved in the new work. “It really highlights how visual that animal is.”

The fruit fly larva has a simple eye and about 40 visual neurons, relying primarily on its sense of smell instead. Studying how the brain builds the visual system as the insect transitions from a larva to an adult could help elucidate how new circuits integrate into existing networks, Winding says, and how more complex brain structures evolved on top of older ones.