A new photometry technique can track absolute levels of dopamine and monitor both fast and slow changes in its concentration in freely moving mice, according to a preprint posted on bioRxiv in January.

The approach, called fluorescence lifetime photometry at high temporal resolution (FLIPR), could be applied to other neurotransmitters and may help the field understand how fast and slow signals differ in the brain, says Erin Calipari, associate professor of pharmacology at Vanderbilt University, who was not involved in the research. “The dopamine field has been trying to answer this forever, since the ’80s.”

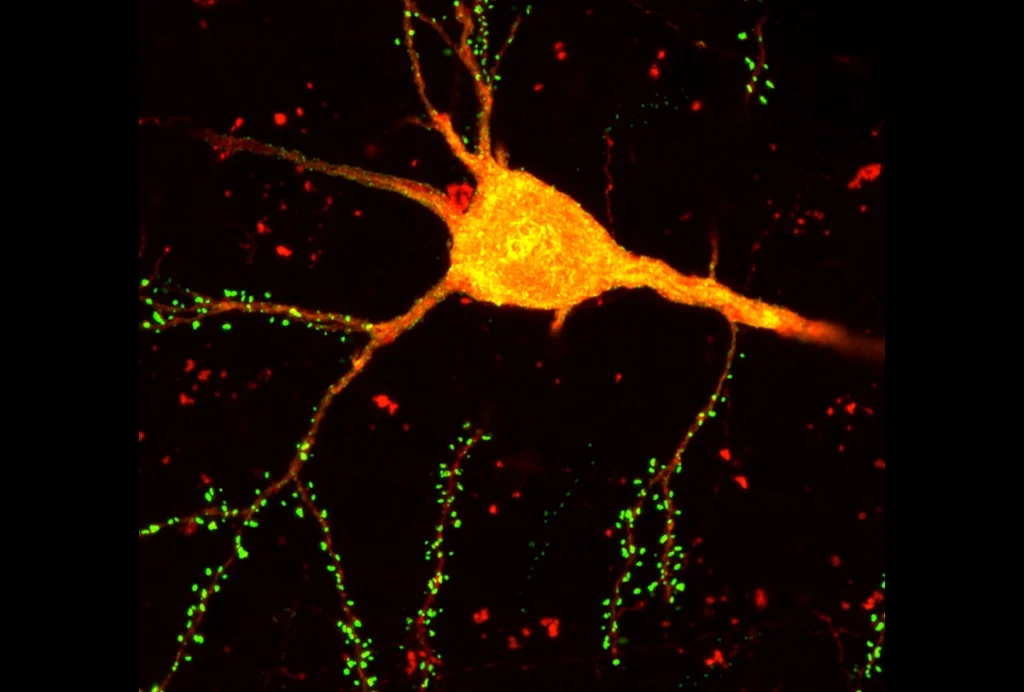

Like other fluorescence-based methods, FLIPR tracks a genetically engineered fluorescent sensor that changes its brightness in the presence of dopamine. But traditional fluorescent imaging techniques rely on shifts in the intensity of the sensor’s glow to gauge relative changes in dopamine levels—a measure that can vary depending on the experiment, an animal’s movement, the amount of sensor expressed and how much the fluorescent molecule, or fluorophore, fades over time. By contrast, FLIPR measures the length of time the sensor remains in an excited state after it absorbs a pulse of light from a fiber optic implant in the brain, which provides an absolute measure—in picoseconds to nanoseconds—of dopamine level changes.

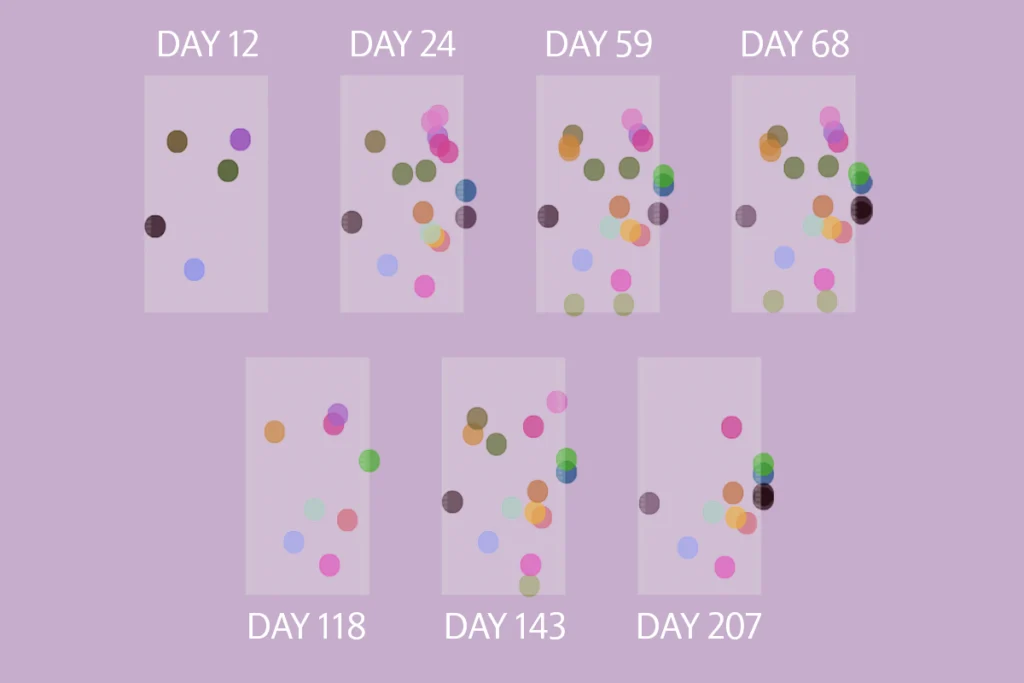

Existing fluorescence lifetime imaging methods are typically optimized to detect only fast, or phasic, changes in neurotransmitter concentration, says study investigator Bart Lodder, a graduate student in Bernardo Sabatini’s lab at Harvard University. As a result, slow, or tonic, signaling has been understudied, Lodder says. “The field has put an enormous emphasis on phasic dopamine,” which is released briefly in response to a stimulus, such as a rewarding drop of juice, he says. “But these slow changes, these tonic changes in dopamine, have actually been very hard for people to measure.”

With FLIPR, researchers can monitor both tonic and phasic dopamine release simultaneously, and at absolute levels, which is important for understanding their interplay, Lodder says.

T

he previous generation of these imaging technologies can record only one fluorophore at a time at a specific temporal resolution and requires periods of “dead time” after each photon is processed. These factors limit how quickly the tool can count photons, says Nicolas Tritsch, assistant professor of neuroscience at McGill University, who was not involved in the new study. “Not only was the prior equipment expensive, but it’s also very time consuming.”Sabatini’s team hand-built the new fluorescence lifetime photometry system and an analog processing unit to record multiple fluorophores at varying temporal resolutions, without dead time. FLIPR can record fluorescence lifetime thousands of times per second, whereas other photometry methods can record lifetime only once per second, the new study shows. It cost the Sabatini Lab about $38,000 to build the FLIPR system, roughly $30,000 less than a commercially available fluorescence lifetime photometry system, and the new system works at higher speeds, says Sabatini, principal investigator on the study and professor of neurobiology at Harvard Medical School.

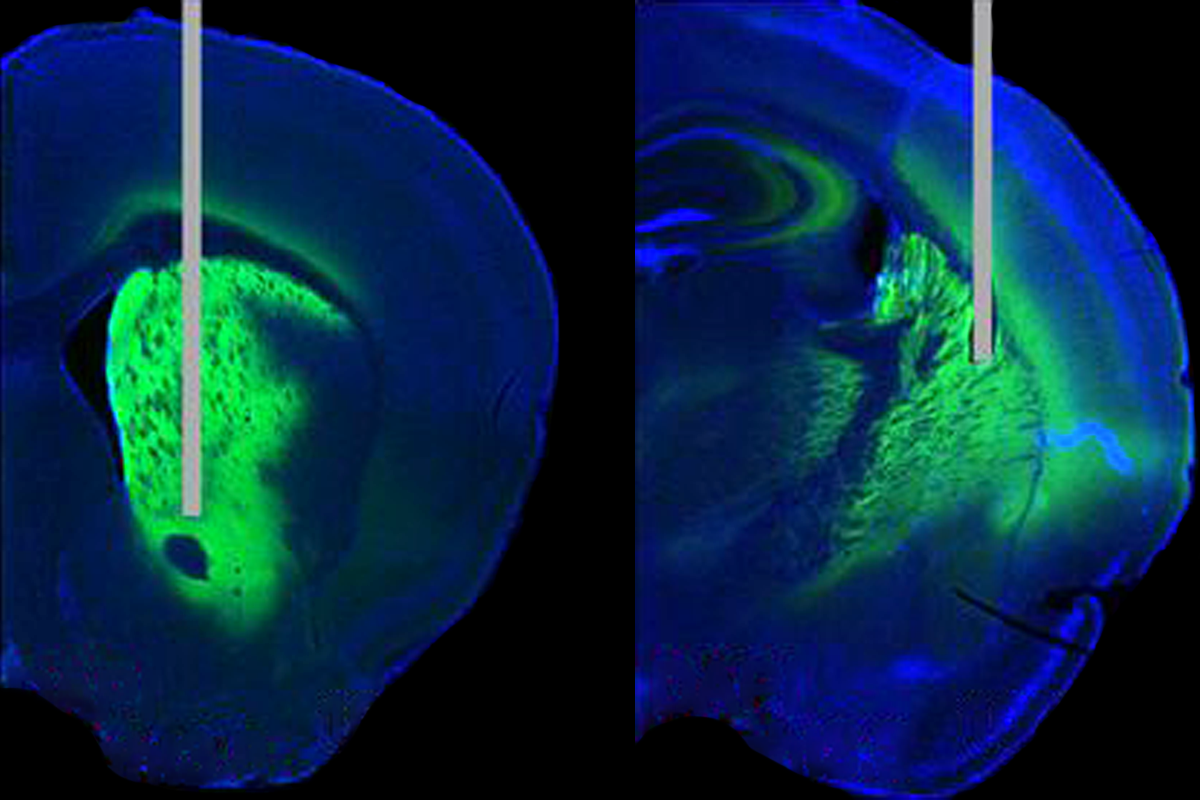

And because the new tool enables absolute and simultaneous measurements of neurotransmitter signaling, it can reveal differences across brain regions that were previously difficult to study via relative measurements, Lodder adds. For example, baseline dopamine levels are higher in the tail of the striatum than in the nucleus accumbens in freely moving mice, the new work shows. And in response to a mild foot shock in the mouse, dopamine rapidly increases in the tail of the striatum before returning to baseline—an expected phasic signal—but does not change in the nucleus accumbens. After a series of shocks, though, dopamine shows a longer-lasting tonic increase in the tail of the striatum and a tonic decrease in the nucleus accumbens.

Phasic dopamine effects depend on baseline receptor occupancy, which is determined by tonic dopamine levels, Lodder says.

B

ecause the new approach does not rely on specific dopamine properties, it can be modified to measure other molecules, too, Lodder says. “All you need is a proper sensor.”Few sensors are capable of lifetime measurement of neuronal signals, says study investigator Lin Tian, scientific director of the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience, who developed the dopamine sensor. But her lab is working to develop more, she adds.

Still, FLIPR’s advances may not be accessible to all researchers, says Adam Bowman, fellow and principal investigator at the Salk Institute for Biological studies, who was not involved in the research.

Because FLIPR is new, for now it must be built by hand, which may be a barrier for some labs, he says. “I think there definitely needs to be a role for some commercialization of these tools so that they’re more plug and play, rather than having to build your own.”

Sabatini says he plans to provide schematics to labs looking to implement FLIPR and is helping other labs build their own system. His lab also is building a circuit board for analog processing, which he says he hopes will be available to order within the next few months.

And researchers may want to see some continued validation of its success, Calipari says. But once those hurdles are cleared, FLIPR could be the “next thing” in imaging, she adds. “It’s going to revolutionize how we’re looking at different kinds of signals in the brain that are changing on different time scales.”