One night in 1995, while watching TV, cognitive neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire got an idea for a new experiment. She was watching a made-for-TV movie called “The Knowledge,” which follows a group of men studying for the London taxi-driver examination—a grueling, years-long endeavor that involves memorizing every street in London.

“She realized immediately that these were rather special people who had very extreme abilities at navigation,” recalls Chris Frith, emeritus professor of neuropsychology at University College London (UCL) and Maguire’s postdoctoral fellowship supervisor at the time, and she wanted to find out if those abilities were reflected in their brain structure.

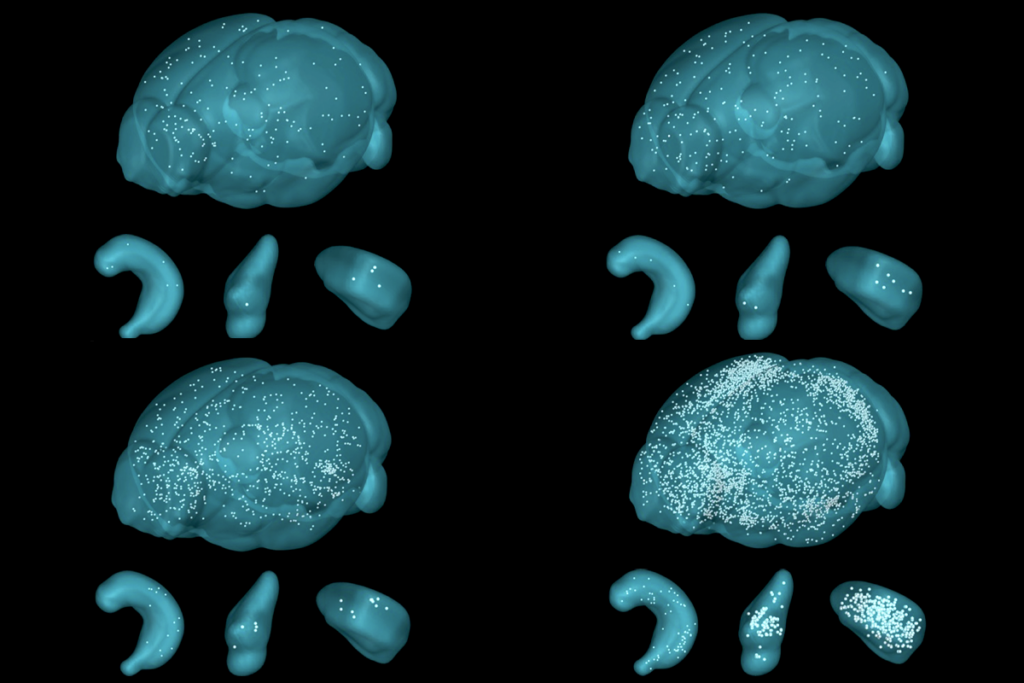

As it turned out, taxi drivers have larger posterior hippocampi than do controls who do not drive taxis, Maguire reported in a 2000 paper, and the longer their career, the greater the volume. It was one of the first demonstrations that experience changes brain structure in adulthood; it garnered media attention around the world and landed Maguire an Ig Nobel Prize in 2003.

It also earned her the admiration of taxi drivers. On the way to the Ig Nobel Prize award ceremony in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Maguire, who was professor of cognitive neuroscience at UCL, chatted with her taxi driver about her work. He gave her half off the fare “for showing that taxi drivers are special,” Maguire shared in her acceptance speech.

Although the taxi-driver study was her most famous work, she was also a “trailblazer” for the cognitive neuroscience of memory, says Felipe De Brigard, associate professor of philosophy and of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. “There are things that we can do and possibilities that were opened to us in researching autobiographical memory, thanks to her.”

Maguire, who died 4 January, was an early adopter of using naturalistic stimuli and asking participants about their thoughts in memory neuroimaging experiments. She theorized that the hippocampus builds scenes to carry out its functions—including navigating, recalling episodic memories and imagining future and fictional scenarios.

“She really did change the way we understand how human memory works,” Frith says.

M

aguire studied psychology as an undergraduate at University College Dublin and completed an M.Sc. in neuropsychology at Swansea University. In 1991, she returned to her hometown of Dublin to work as a neuropsychologist with people who had developed amnesia after having a temporal lobe removed to treat their epilepsy. She planned to study this cohort for her Ph.D. but was “unsure what to focus on,” she said in an interview in 2012.She read a paper summarizing the book “The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map,” by John O’Keefe and Lynn Nadel, and it “cemented everything,” she said. Rats with a lesioned hippocampus perform poorly on navigation and spatial-cognition tasks, the researchers described. But work in people with damaged hippocampi—such as those Maguire worked with—had implicated the region only in memory.

Her resulting Ph.D. project “bridged this gap” in the literature, Frith says. Maguire played videos of a cyclist’s ride through Dublin and quizzed participants on the routes. People missing one of their temporal lobes performed worse on the task than controls, demonstrating impaired spatial cognition.

After her Ph.D., Maguire joined the Functional Imaging Laboratory at UCL and continued to study navigation and spatial memory. She was one of the first people to use virtual reality in cognitive neuroscience experiments, and she also devised methods to study autobiographical memory using functional MRI (fMRI).

In one fMRI experiment she conducted, participants received gifts from characters in a virtual-reality environment and later recalled each exchange. She also prompted participants to think of specific past experiences while in the scanner.

“She was extremely imaginative in figuring out what one might do, using real-world-type situations, to try to link memory theory to what actually goes on in people as they go around their everyday lives,” says Michael Rugg, distinguished chair in behavioral and brain sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Several of Maguire’s experiments built on the taxi-driver study. London bus drivers, who drive just as much but only along established routes, have a smaller posterior hippocampus than taxi drivers do, she found, and the size does not correlate with the amount of experience. And that same brain region grows over three to four years of training only in prospective taxi drivers who ultimately pass the Knowledge of London test, she discovered in another project.

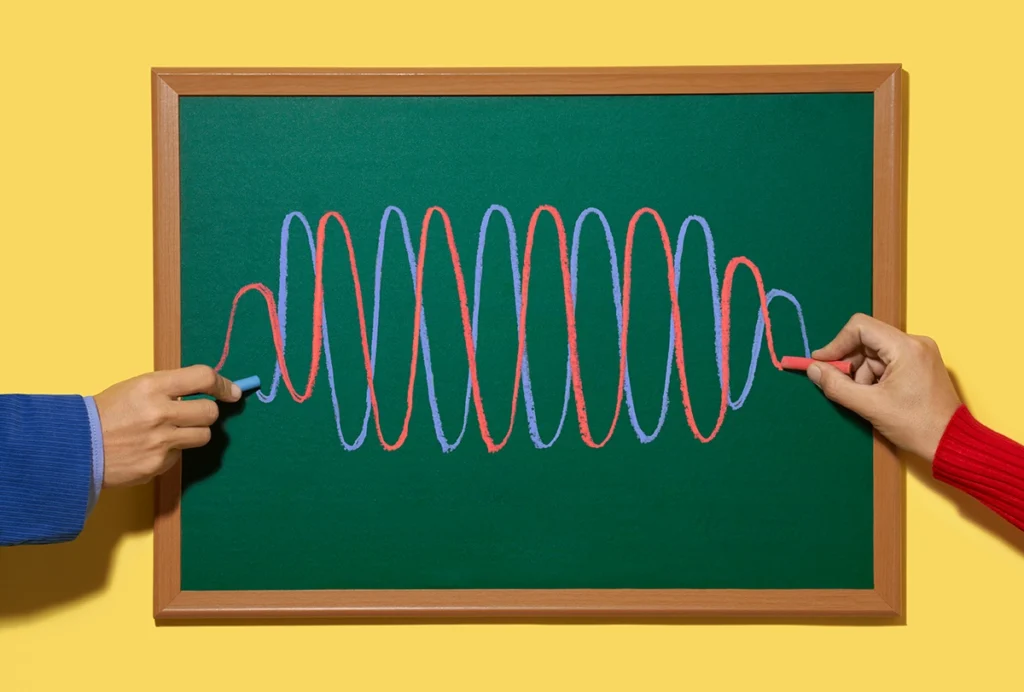

Other taxi drivers in her studies had their brains scanned while they navigated a virtual London in “The Getaway,” a 2002 video game that accurately depicts more than 70 miles of the city’s streets. As soon as they finished the scan, the taxi drivers watched a playback of their game performance, critiqued their choices and shared what they were thinking at each moment—“a bit like a sports commentary,” says Hugo Spiers, professor of cognitive neuroscience at UCL and a former postdoctoral researcher in Maguire’s lab.

Most scientists would have stopped at measuring the driver’s behavior and testing their memory and choices, “but [Maguire’s] idea at the time was, ‘Why don’t you ask them what they’re thinking?’” he recalls. The upshot was that Maguire and Spiers could then analyze each second of the fMRI data based on which navigational task—monitoring traffic, planning a route, inspecting the scene—the participants said they were doing at the time.

Asking participants what they think or prompting them to think of something specific, also known as introspection, remains controversial in imaging experiments, De Brigard says. It is “basically giving the independent variable to the subject.” But Maguire demonstrated that it can be rigorous, De Brigard says, “and I think that that helped to expand the research in autobiographical memory and cognitive neuroscience in very, very useful ways.”

M

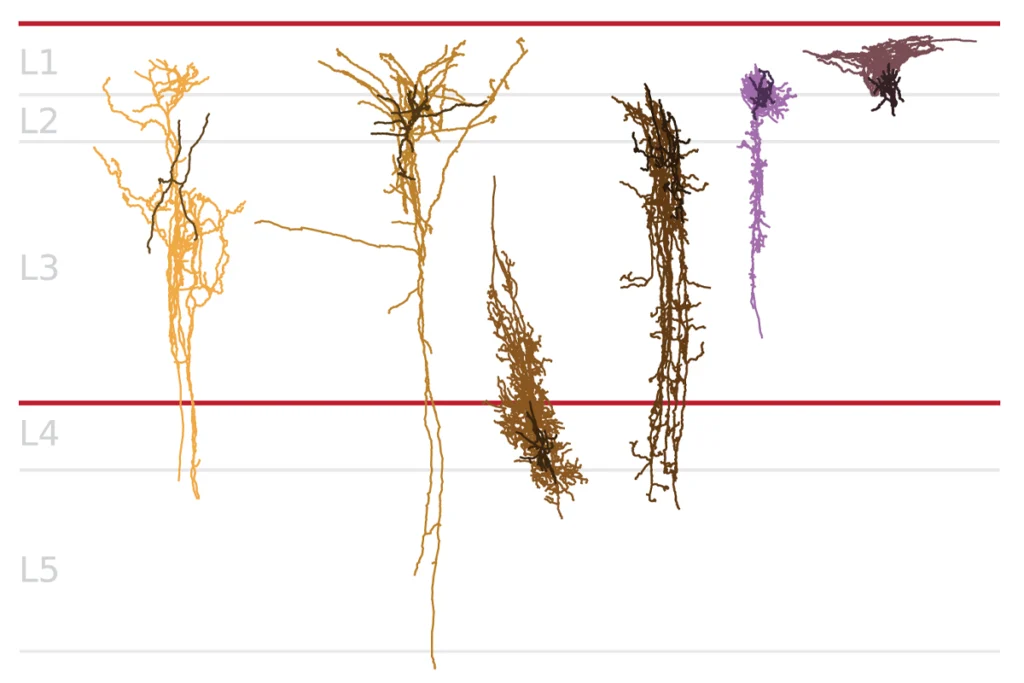

aguire was a “very strong and original” experimentalist and methodologist, Rugg says, but she also engaged deeply with theory and had some “super interesting ideas.”For example, Maguire and her team reported in 2007 that people with damaged hippocampi cannot imagine new experiences. The participants struggled to build a spatial scene of something that hadn’t happened yet, in the same way that they cannot construct scenes of their past experiences. This discovery led her to develop the scene construction theory, which asserts that the different functions of the hippocampus are all oriented around space. “I think that was a very important insight into how cognition in the brain works,” Frith says.

Other memory researchers in the field disagreed with her theory, and argued that the hippocampus instead combines relevant details to remember experiences and imagine new ones, but Maguire always “stuck to her guns,” Rugg says. She engaged her colleagues in fierce intellectual debates, both in the literature and in person, but it always “came from a real sense of scientific integrity,” says Cathy Price, professor of cognitive neuroscience at UCL and Maguire’s longtime friend. In the end, “it was a very constructive disagreement,” De Brigard says, “because Eleanor was very critical but always stopped short of being dogmatic.”

Research was Maguire’s great passion, and “she was completely focused and pragmatic,” Price says. She worked seven days a week, often from 8 in the morning until 8 in the evening. Even when she became a supervisor and took on more leadership duties, she still prioritized time in the lab, Price says. “She was hungry for knowledge.” But she was fun to be around, too—Maguire was an avid fan of the Crystal Palace Football Club and Ireland’s national rugby team, and she often made “wry comments” that made people laugh, Price says.

Maguire had a “wonderful way of working with people,” Spiers says, whether a person with amnesia, a taxi driver, a member of the university’s support staff or a trainee. “She cared deeply about her students and wanted to make sure that they all landed on their feet and [she] could see them through,” says Morris Moscovitch, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Toronto. Yet she also set high standards for them, Price says. “She didn’t let them get away with anything, really.” For Spiers, working in Maguire’s lab was “probably the happiest academic period of my life.”

Maguire was diagnosed with spinal cancer at the end of 2022 and died this month at age 54 from pneumonia. In the last few years of her research career, she worked on mobile magnetoencephalography and methods for analyzing the structure of the hippocampus.

“She was not someone winding down her career. She had 20, 30 more years,” Spiers says. “She could have told us a lot.”