Remarkable discoveries over the past 80 years have transformed neurobiology from what was largely an offshoot of histology and neurology into a multidisciplinary powerhouse that has generated deep insights into the structure, function, molecular architecture and development of the nervous system. These advances relied almost entirely on studies of model organisms, such as rodents, fish, flies and nonhuman primates. We have reached a point where we can apply these insights to the human brain; I believe that the next few decades will witness revolutionary discoveries about how our brains function—and how, all too often, they malfunction. If I were starting my career today, I would focus on human neurobiology. But as that is no longer an option, I am guest-editing this new series of essays for The Transmitter, inviting colleagues to weigh in on what’s to come and the methods we can deploy to get there.

A host of technical, legal and ethical issues make the human brain difficult to study. Given the vastly greater accessibility of model systems, why should basic researchers target the human brain, and why is now the right time for an increased effort?

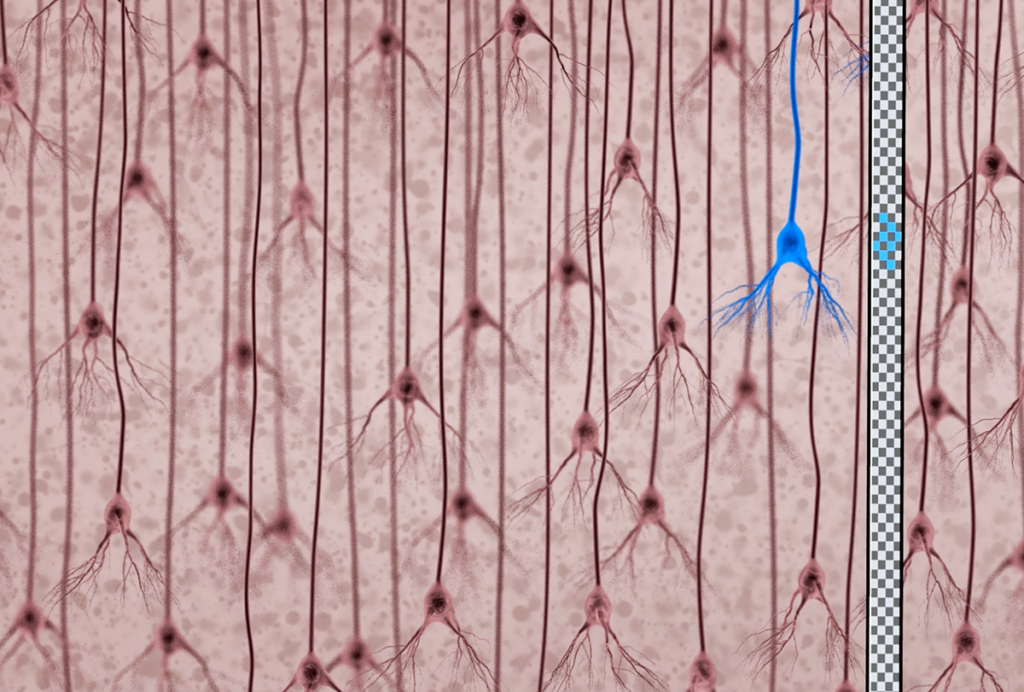

The most obvious answer to the first question is clinical relevance. But that’s not the only compelling reason: Many features of the nervous system are not only primate-specific but human-specific, and the latter set of traits is likely to underlie human-specific mental abilities, such as language and creativity. Human brains are three times larger than those of great apes, with a larger frontal cortex, more types of neurons and glial cells, more complex dendritic and astrocytic arbors and higher connectivity among association areas. Particularly intriguing is the fact that brain development and plasticity extend further into the postnatal period in humans than in even our closest relatives, providing a longer interval in which experience can remodel the nervous system. These structural and developmental features are accompanied by, and presumably due to, human-specific molecular features. Indeed, researchers have identified many human-specific protein isoforms and regulatory elements, and even a few human-specific genes. Some of these reside in “human accelerated regions” or HARs, genetic segments that are conserved across mammals but distinct in humans.

Why now? Again, two reasons. The first is the plethora of discoveries from model organisms that are beginning to give us satisfactory—albeit incomplete—accounts of how neurons form, connect and function. These discoveries could not have been made in human tissue, but they can now guide our progress.

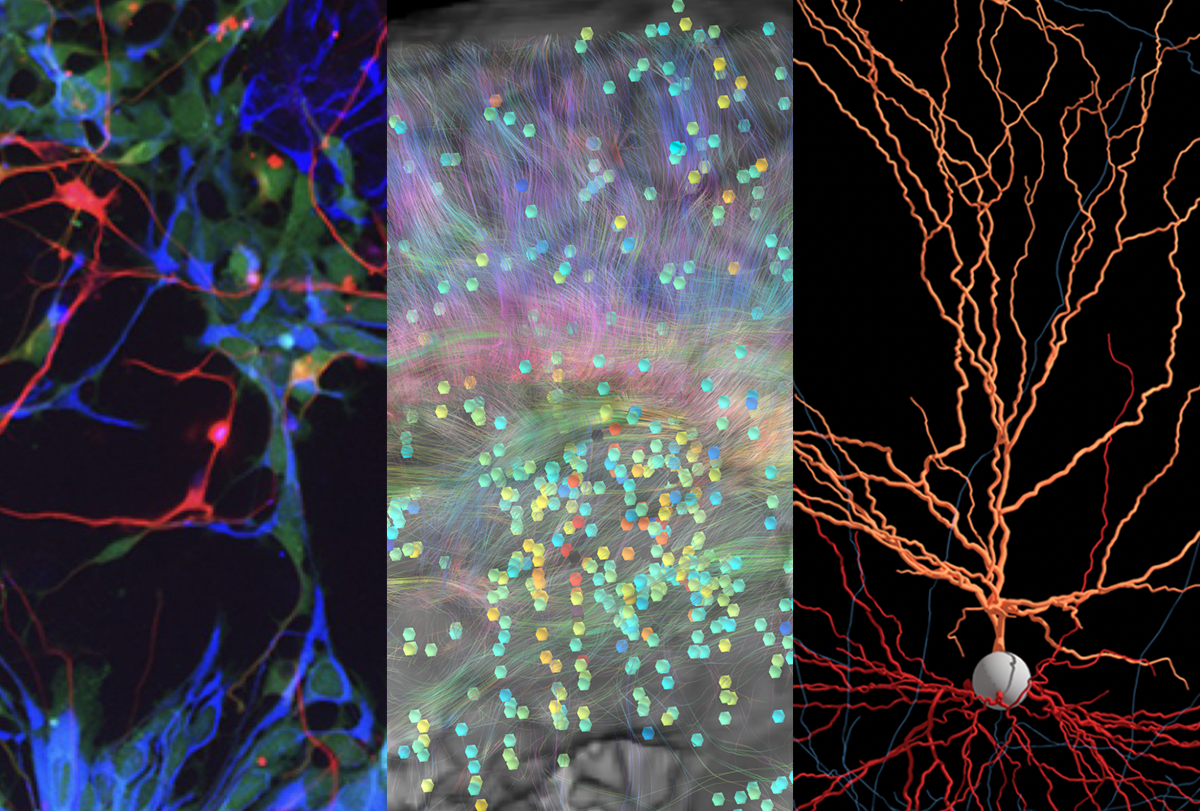

Second is the invention of ever-increasing numbers of sophisticated tools that can be used to probe the human brain in ways that would have been unthinkable a few decades ago. In this respect, human neurobiology follows a well-established path, in which progress has been driven in large part by technical developments. In the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, electrophysiology dominated. Neuroscience giants, including Alan Hodgkin, Andrew Huxley, Bernard Katz, Stephen Kuffler, Vernon Mountcastle, David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel, discovered how brain cells generate resting, action and synaptic potentials and took the first steps toward showing how neural circuits process information. Their discoveries were enabled by the inventions of the voltage clamp, glass and tungsten microelectrodes, and the introduction of commercial oscilloscopes. In the 1980s and 1990s, molecular neurobiology came into its own, with the advent of monoclonal antibodies, gene cloning and sequencing, as well as methods to genetically engineer knockout and transgenic animals. The first decades of the 21st century saw major advances in systems neuroscience, enabled by new methods for simultaneously recording from and stimulating specific neurons using optogenetics, calcium imaging and, more recently, voltage imaging and Neuropixels probes.

This all follows Nobelist Sydney Brenner’s dictum that “progress in science depends on new techniques, new discoveries and new ideas, probably in that order.” Funding agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), have recognized Brenner’s wisdom: Just look at the full name of the highly influential NIH BRAIN Initiative: “Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies.”

F

or studying the human brain, we are now roughly where we were for electrophysiology in 1945, molecular biology in 1980 and systems neurobiology in 2005. We have access to and are employing extraordinary methods, but we have a long way to go. Subsequent essays in this series will explore some of the following methods and how researchers are using them to decipher the human brain:- Organoids and assembloids make it possible to generate 3D cultures of human central neurons that recapitulate some aspects of brain function and connectivity. These structures can be used to study early events in brain development—and because they can be generated from donors with known brain diseases, they can be used to probe how cellular and molecular processes go awry and even to test potential therapeutic approaches.

- Organoids are best suited to studying development—their component cells fail to mature and therefore cannot faithfully recapitulate adult function. Xenotransplants, in which human neural progenitors or even organoids are transplanted into the rodent brain, offer an alternative for studying cells and circuits in the adult human brain. They mature to a far greater extent than isolated organoids and even establish bidirectional connectivity with host neural circuits.

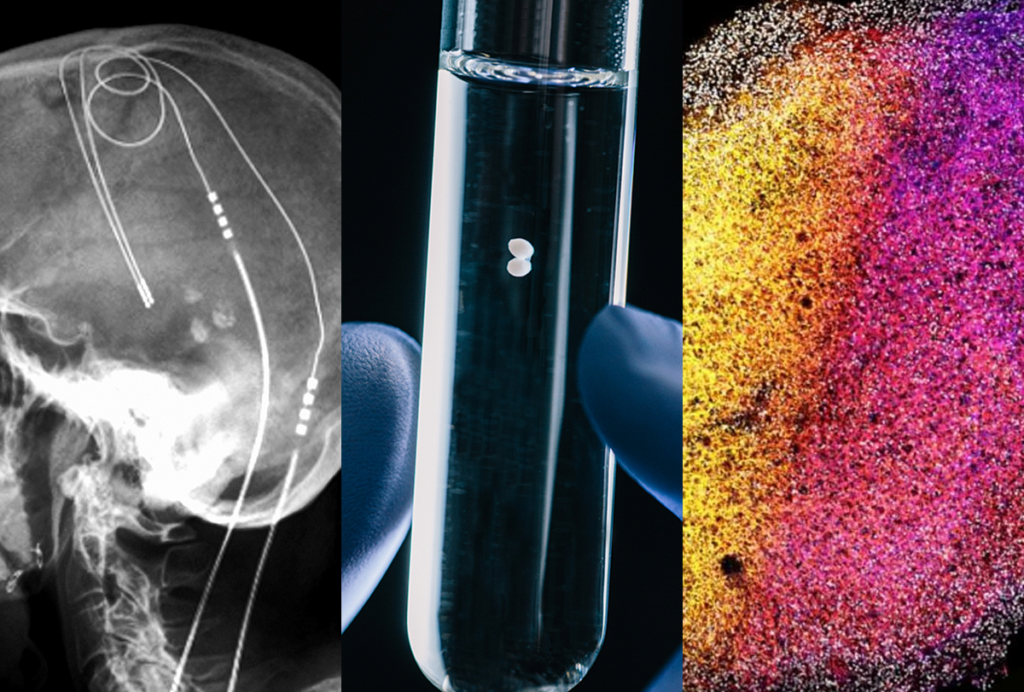

- For monitoring the live human brain, neuroimaging, including MRI and functional MRI, have long been the key methods. Dramatic improvements in these technologies are now enabling investigators to map circuit activity with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution. In addition, intracranial recording from small groups of neurons or even single neurons in neurosurgical patients make it possible to perform in humans the types of studies that revealed principles of circuit function in model organisms. That means that researchers can probe circuits underlying human-specific mental activities, such as language.

- As powerful as neuroimaging and intracranial recording are, they remain cumbersome, expensive and, for intracranial methods, limited to a small number of patients. But a suite of rapidly improving technologies, including transcranial magnetic stimulation and magnetoencephalography, are enabling extracranial, noninvasive stimulation and recording. For better or worse, some stimulation methods are now being commercialized and sold directly to consumers.

- On the cellular level, new technologies now make it possible to analyze gene expression and epigenetic features in thousands of individual cells from postmortem samples. This is a vast improvement over previous molecular and neurochemical methods, which analyzed large chunks of brain tissue, inevitably missing cell-type-specific features. Using these new tools, researchers have classified and characterized hundreds of neuronal types in the human brain and are pinpointing the specific types affected in brain diseases. Even more recently, a suite of methods called spatial transcriptomics enables this profiling in intact tissue, retaining information about cells’ location in the brain.

- The sheer volume of data collected by these and other methods is overwhelming—and growing rapidly. It is impossible to analyze by conventional methods, and the lessons it teaches us are no longer intuitively comprehensible in the way that, say, action potentials or simple or complex cells in the visual cortex are. To make sense of this, computational and theoretical neuroscience will need to play a central role.

Over the next few months, essays in this series will describe some of these new technologies—what they are, what they are telling us and what more they can tell us as they advance.