Single-cell genomics technologies and cell atlases have ushered in a new era of human neurobiology

Single-cell approaches are already shedding light on the human brain, identifying cell types that are most vulnerable in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, for example.

Studying the human brain is hard. Really, really hard. It is roughly 1,000 times the size of a mouse brain, with extreme cellular and circuit complexity. It is largely inaccessible to experimentation using the kinds of approaches that have been hugely successful in model organisms, and access to human brain tissue is limited to postmortem donations and rare instances of tissues obtained from surgeries and biopsies. Making the situation even more challenging, human brains are highly variable, as a result of both genetic and environmental factors, making it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions.

Despite these difficulties, however, understanding the human brain is imperative; it is the source of philosophy, art, science and engineering. On the practical side, many brain disorders manifest uniquely in people.

Studying the human brain requires highly scalable technologies that can be applied to a vast number of cells and large tissue volumes at cellular or subcellular resolution, and to a large number of people with a variety of genetic and demographic backgrounds. The technologies should enable investigation of the human brain at different levels—from genes to cells, networks and whole-brain systems—as well as integration across these levels.

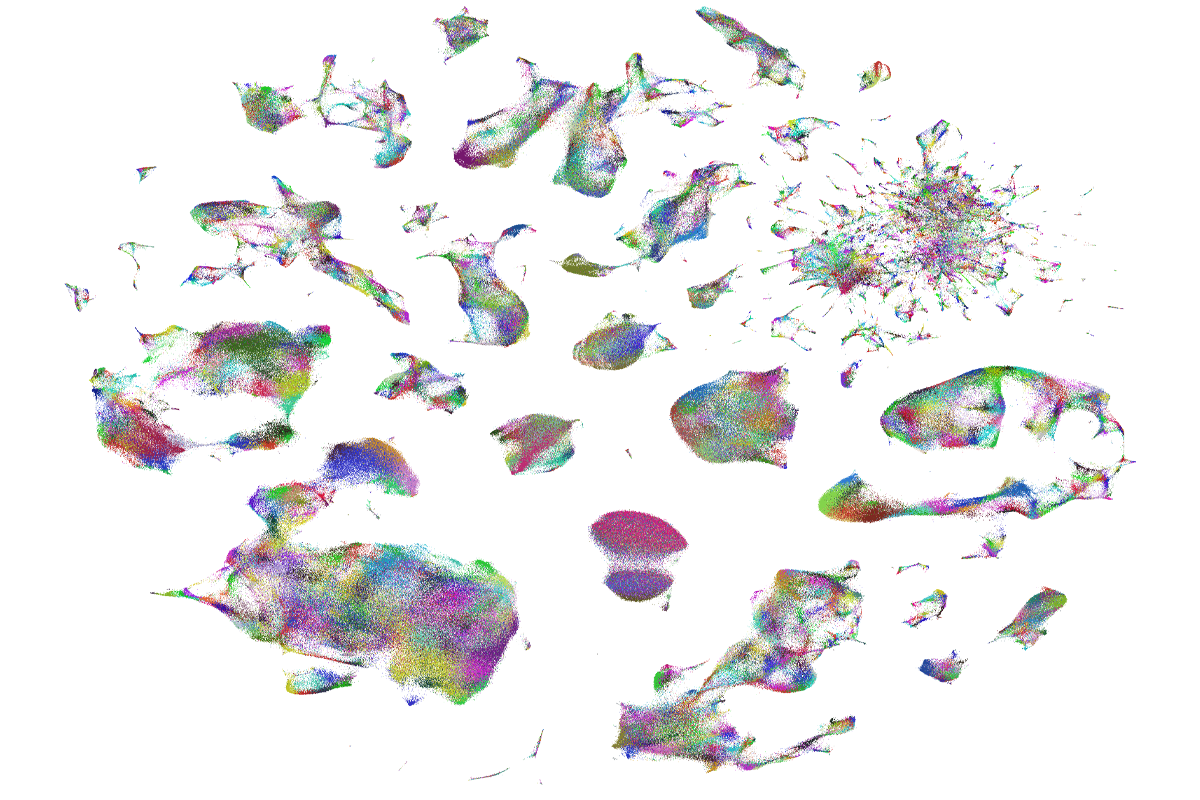

Over the past 15 years, single-cell genomics technologies have filled this need, rapidly opening up a whole new field of human neurobiology centered on the brain’s cellular architecture. Just as the genome carries the information to create an entire organism, individual cells gain their identity and properties from the set of genes in active use. Single-cell transcriptomics methods that measure more or less the whole set of genes in individual cells or nuclei capture these molecular fingerprints.

Applied to human brain tissues from postmortem or surgically acquired samples, these methods simultaneously classify cell types and characterize their molecular profiles across thousands of genes. Large-scale efforts, such as the National Institutes of Health BRAIN Initiative’s Cell Census projects, are applying these methods across the entire brain to create comprehensive brain cell atlases. The first brain-wide cell atlases of mouse and human—based on deep, unbiased profiling of millions of cells—were published nearly simultaneously, though the mouse version was much more complete and included spatial information.

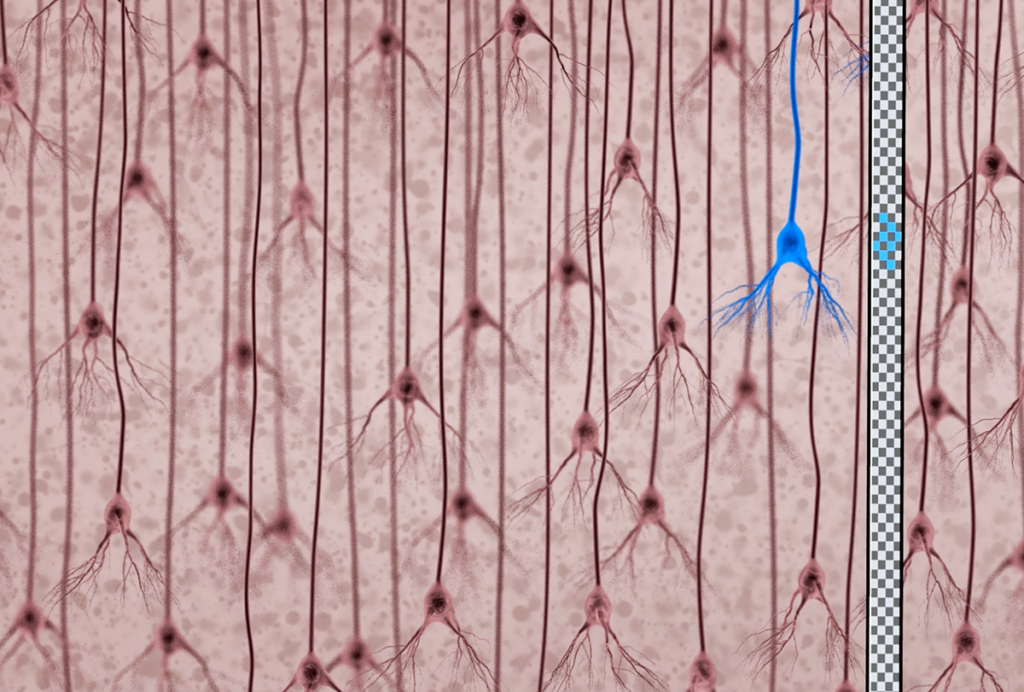

Brain cell atlases have produced several key findings. First, the brain is exceptionally complex compared with other organs, comprising more than 5,000 molecularly distinguishable types of cells, mostly neuronal, that are highly regionalized across the brain and can be represented by a hierarchical taxonomy similar to that of species. Any given region of the brain has high cellular complexity, and this complexity can now be defined. By comparing cellular atlases of different species, we know that the overall cellular blueprint of the mammalian brain is well conserved to a certain level of granularity; that means we can quantitatively align human cellular classifications with those of model organisms and determine which features are conserved or species-specific.

Put altogether, these brain cell atlases are both descriptive and explanatory, and foundational for neuroscience in essentially the same way that the genome is for genomics. Anchored on the universal language of genes and genomes, meaningful comparisons can be made between cell types across tissues, individuals, species, developmental stages and diseases. Brain cell atlases also lay the foundation for studying the human brain at the network and system levels, by translating knowledge gained from model organisms to humans and providing molecular tools to label and target specific cell types in anatomical and functional studies.

I

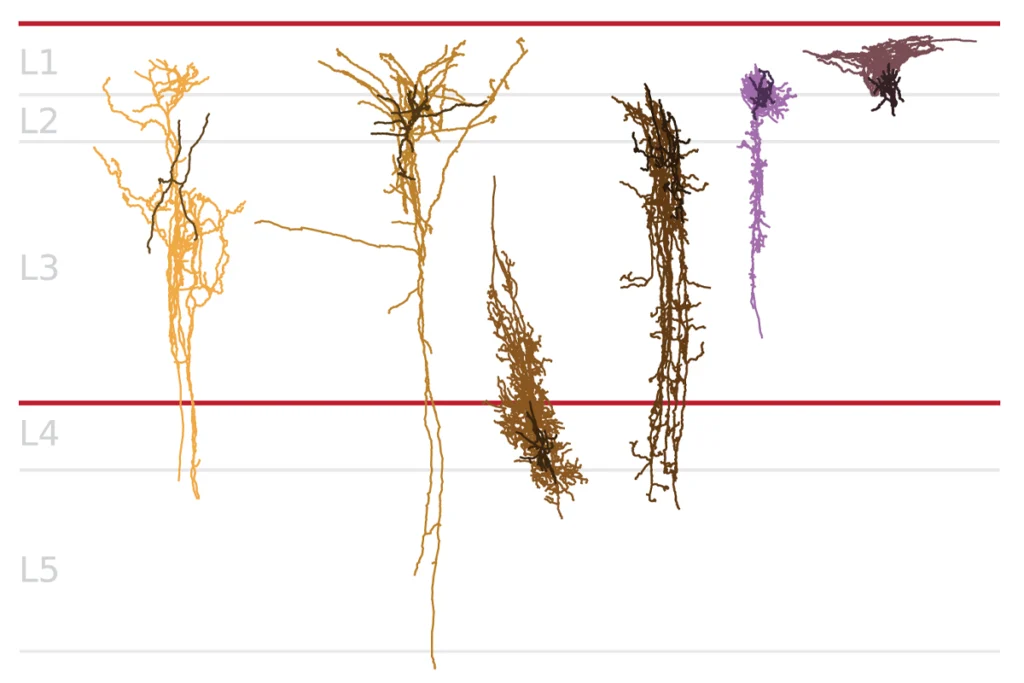

n addition to single-cell transcriptomics, several other single-cell technologies are adding more layers to the study of human brain tissues. Tools for assessing epigenomics can detect accessible regions of chromatin, DNA methylation sites and binding sites of specific chromatin-associated proteins, such as transcription factors. These are particularly important, because like transcriptomics, epigenetics varies substantially from species to species, making it essential to investigate it in various human brain cell types.Spatially resolved transcriptomics tools analyze the spatial distribution of cells and gene-expression signatures in tissue sections. These cellular-resolution spatial technologies are powerful in revealing tissue heterogeneity, functional niches, spatial gradients and cell-to-cell interactions. Finally, an increasing suite of technologies combine transcriptomics with other methods, such as multi-omics for transcriptomics and epigenomics; Patch-seq for transcriptomics, morphology and physiology; and MAPseq/BARseq for transcriptomics and axonal projections. It is already clear that this technology wave will extend beyond DNA and RNA, with major advances in highly multiplexed proteomics and connectomics that are now being applied to the human brain.

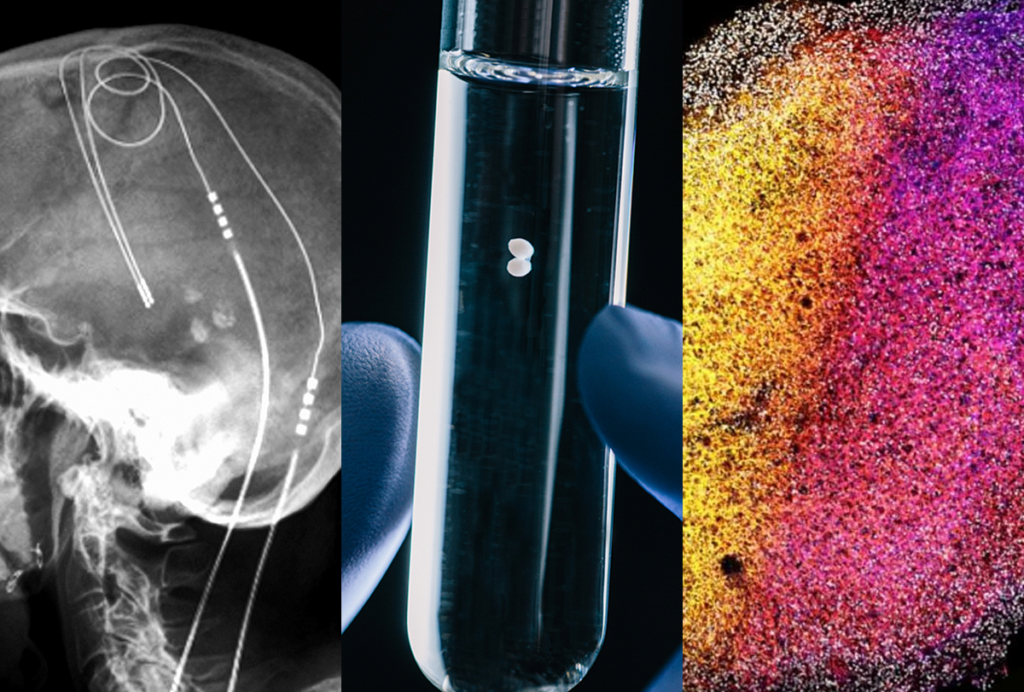

Though cell atlases are primarily descriptive in nature, they also enable the development of new tools for manipulative neuroscience. Using atlas data, for example, researchers have created suites of tools to drive gene expression in specific brain cell types in a range of species, using newly discovered enhancers. These tools are incredibly important for neuroscience as a field, expanding the capacity to selectively label and genetically manipulate cells from mainly mice to any species. For the human brain, this opens the door to new types of experiments in live tissue from surgical resections; researchers can use these tools to target specific genes, cells and circuits to study their function. These tools may also one day form the basis of precision gene therapies for brain disorders.

Cell atlases and single-cell tools are already shedding light on brain disease. In our own Seattle Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Cell Atlas project, for example, we studied a cohort of postmortem brain specimens spanning the spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease pathology and found that certain types of neurons are selectively vulnerable at early stages of disease. This joins many other observations of selectively vulnerable cell populations and molecular changes in Alzheimer’s and other degenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and ALS. Similarly, in Huntington’s disease brain tissues, combining single-cell transcriptomics with measurement of the CAG-repeat lengths uncovered cell-type-specific somatic expansion of the CAG repeats associated with profound gene expression changes as a potential cause of neurodegeneration. It is now possible to see a path from descriptive “discovery science” efforts to identification of the affected cell populations in any disease, and development of tools and therapeutic strategies to selectively target those vulnerable populations.

Looking to the future, we are entering a new era of human neurobiology enabled by new technologies and paradigm-setting cell atlases. Some barriers remain to taking full advantage of these technologies and knowledge, most notably the need for more brain donation and improvements in brain preparation, preservation and distribution. Nevertheless, we predict these atlases will be part of the fabric of everyday neuroscience research in 10 years and will prove themselves to be profoundly useful for studying human brain structure and function, and the detailed cellular, molecular and circuit basis of brain diseases, which may finally lead to breakthroughs in new treatments and cures.

Recommended reading

Why the 21st-century neuroscientist needs to be neuroethically engaged

Thinking about thinking: AI offers theoretical insights into human memory

Explore more from The Transmitter

Expanding set of viral tools targets almost any brain cell type

Imagining the ultimate systems neuroscience paper