When I was a psychology major in college with an interest in mental illness, I wrote a term paper on schizophrenia. I was particularly excited by studies on the concordance of schizophrenia between twins—the odds that if one twin had schizophrenia, the other would too. It turned out that concordance was more than twofold higher in identical twins, who share almost all their DNA, than in fraternal twins, who share only about half, suggesting that genetic factors account for much of the susceptibility to the disease.

At the time, this was quite a challenge to the prevailing view that experiential factors, such as childhood trauma or cold parenting, caused schizophrenia. The conclusion was not foolproof, because identical twins also share more environment than fraternal twins do, especially when one fraternal twin is a boy and the other a girl. However, it was later found that biological relatives of adopted people with schizophrenia are several-fold more likely to have schizophrenia than their adoptive relatives, arguing against the idea that the shared environment was primarily responsible.

For me, this work was a main motivator to turn from psychology to molecular neurobiology. For the field, during the last decades of the 20th century, it led to a search for genes altered in people with schizophrenia. The main strategy was to choose and investigate candidates based on prevailing etiological theories. The search was, to put it succinctly, fruitless, and we now realize that available methods were inadequate to the task.

Since then, however, genetic technology has advanced, and the cost of DNA sequencing has plummeted. With the advent of exome and whole-genome sequencing, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and more, it has been possible to “genotype” more than 100,000 people with schizophrenia and far larger numbers of neurotypical “controls.” In this way, researchers have identified more than 300 genetic loci that are more common in people with schizophrenia than in neurotypical controls. As a consequence, it has become clear that there is no “schizophrenia gene.” A small number of genetic variants carry a significant risk of schizophrenia, but they account for only a minuscule fraction of cases. Common variants carry most of the heritability observed in twin studies and only predispose people to the condition—those with a risk variant are slightly (often about 1 percent) more likely to have schizophrenia than those without. This pattern has led to the concept of a “polygenic risk score,” which, in its simplest form, calculates overall risk by adding up the risk conferred by each variant in a person’s genome.

Despite this vast body of work, though, I believe that the bottom line remains the same—genetics has not yet taught us nearly as much as we had hoped about the causes of schizophrenia. Why? Several factors make studying this and other psychiatric disorders especially difficult. Schizophrenia lacks biomarkers and good animal models, both of which have been critically important in unraveling the etiology of other diseases. And schizophrenia is unlikely to be a single disease, so genetic variants present in a subset of cases can be lost when all affected people are considered together.

Here, however, I want to focus on two problems specific to genetic studies of schizophrenia and probably psychiatric disorders in general—one relating to the few genes that are potentially “causal,” and the other to the many genes that affect susceptibility to a small extent. To illustrate, I use the metaphors of automobiles and tuberculosis, respectively.

R

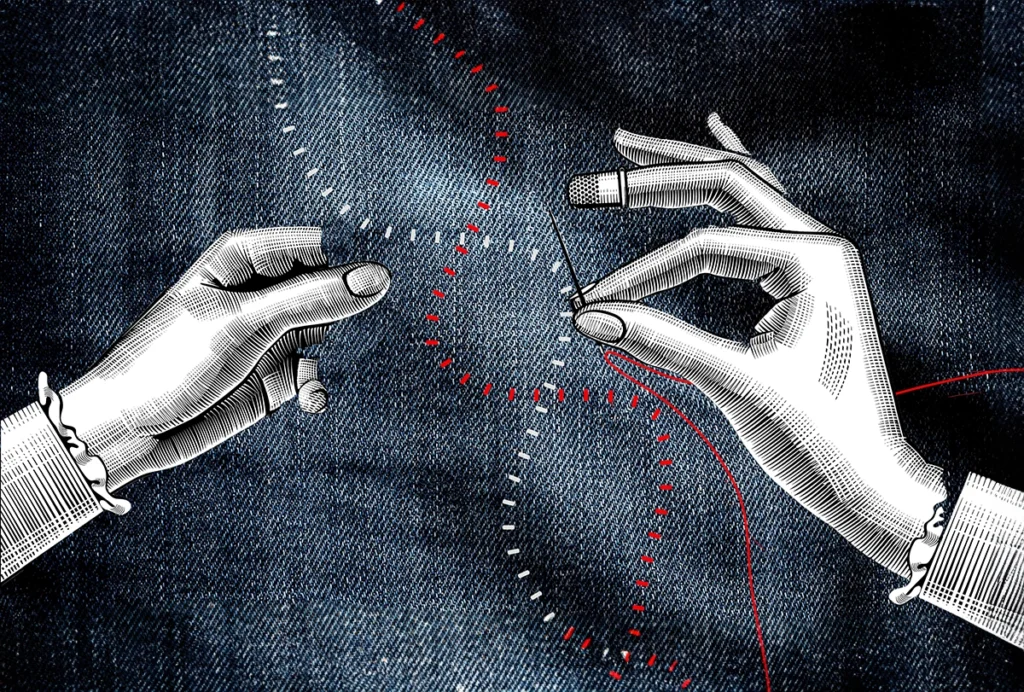

esearchers have identified about a dozen genes in which variants might cause schizophrenia. They are not strictly causal, in that the variants are also found in some neurotypical people. But the odds ratios—the frequency of the variant occurring in people with schizophrenia compared with that in neurotypical people—are impressive and in some cases more than 10-fold. The hope was that these genes would define a pathway that would shed light on the large majority of people with schizophrenia who do not bear any of these “ultra-rare” variants.There was good reason for optimism based on other diseases. A large number of genetic variants found in muscular dystrophies, for example, encode proteins that form the “dystrophin-glycoprotein complex,” which is essential for the tensile strength of the muscle fiber membrane. Alzheimer’s disease offers another example; the first three variants identified in rare, early-onset cases were in amyloid precursor protein (APP) and two components of an enzyme complex (PSN1 and PSN2) that cleaves the APP protein to generate the peptide that forms plaques. In both cases, gene identification has led to a mechanistic understanding and therapies.

By contrast, the variants seen in schizophrenia do not form an obvious complex or pathway—they encode proteins involved in neurotransmission, neuronal migration, nuclear transport and ubiquitination. Why the variety? I believe it is because schizophrenia is fundamentally more complicated than degenerative diseases such as muscular dystrophy or Alzheimer’s. There are many more ways to disrupt cognition than to kill neurons or muscle fibers. This is the car analogy: Suppose you find that a car stopped running because the left rear axle broke. The next time you come across a nonfunctional car, you might start by examining the left rear axle, and then perhaps move on to the left rear tire or the right rear axle, and so on. But without knowing something about how a car works, you wouldn’t have any reason to look at the battery or carburetor or fuel pump or alternator or transmission or gas tank. And if you decided to fix broken cars by replacing their axles, you’d have a very low success rate. In essence, as complex as Alzheimer’s disease and muscular dystrophy are, they are more like bicycles than like cars.

A different problem has plagued GWAS. It was apparent from the first one that this method would come up with genetic loci that had only minor effects on the susceptibility to schizophrenia. That is why it took tens of thousands of cases and painstaking replication in multiple populations to identify loci with confidence. However, as was the case for the ultra-rare variants, it was reasonable to imagine that they might cluster into pathways that could be investigated to understand mechanism or devise therapies. That hasn’t happened so far.

Why the failure? Perhaps the genetics of infectious diseases provides some insight. It turns out that many infectious diseases, including malaria, leprosy, polio and tuberculosis, have a heritable component. For tuberculosis, for example, one estimate of its heritability is close to that of schizophrenia—around 0.5. How could that be? We know exactly what causes tuberculosis (and leprosy and polio), and it is definitely not an alteration in one of our genes. The answer is that the relevant genes encode proteins that affect receptors for the microbe, or the severity of the response, or the amount of inflammation that ensues, or the person’s ability to mount an effective immune response. In other words, if people are exposed to a very high level of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, most will get tuberculosis. If there are very few bacilli in the environment, hardly anyone will. In the middle range, though, variants in “susceptibility genes” have a major influence on who gets sick and how sick they get.

The point here is that unless you already knew that tuberculosis was a bacterial disease, identifying the many susceptibility genes would be unlikely to help you identify the cause. In fact, it could be the opposite, given that many of these genes affect susceptibility to other diseases. You’d be left wondering, as psychiatrists are, why so many different diseases share a considerable part of their genetic architecture. The answer may be that these genes are related to shared factors across disorders rather than the more proximate causes of individual disorders.

What should we conclude? I certainly don’t question the value of searching for genes that cause or confer susceptibility to disease and provide therapeutic targets. There have been far too many triumphs to leave any doubt that genome sequencing of various sorts will continue to be a centerpiece of disease-relevant research. On the other hand, in the realm of the brain, genetic approaches may be more valuable in studies of diseases in which cells appear to malfunction or die—generally neurodegenerative or neurological disorders—than those in which circuits appear to malfunction without obvious cellular pathology—generally behavioral or psychiatric conditions.

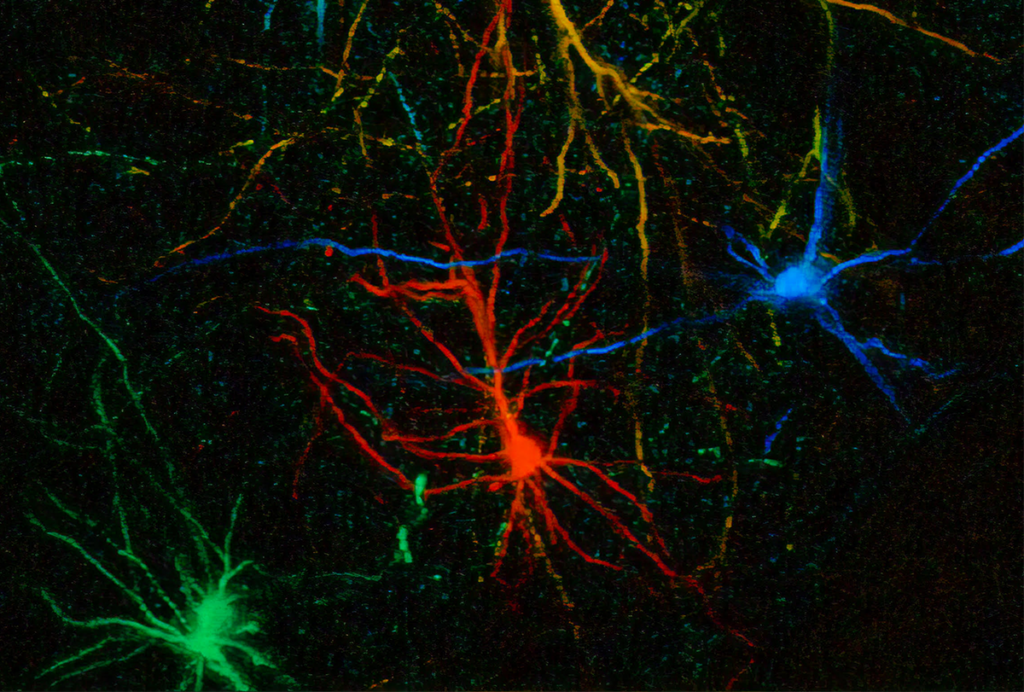

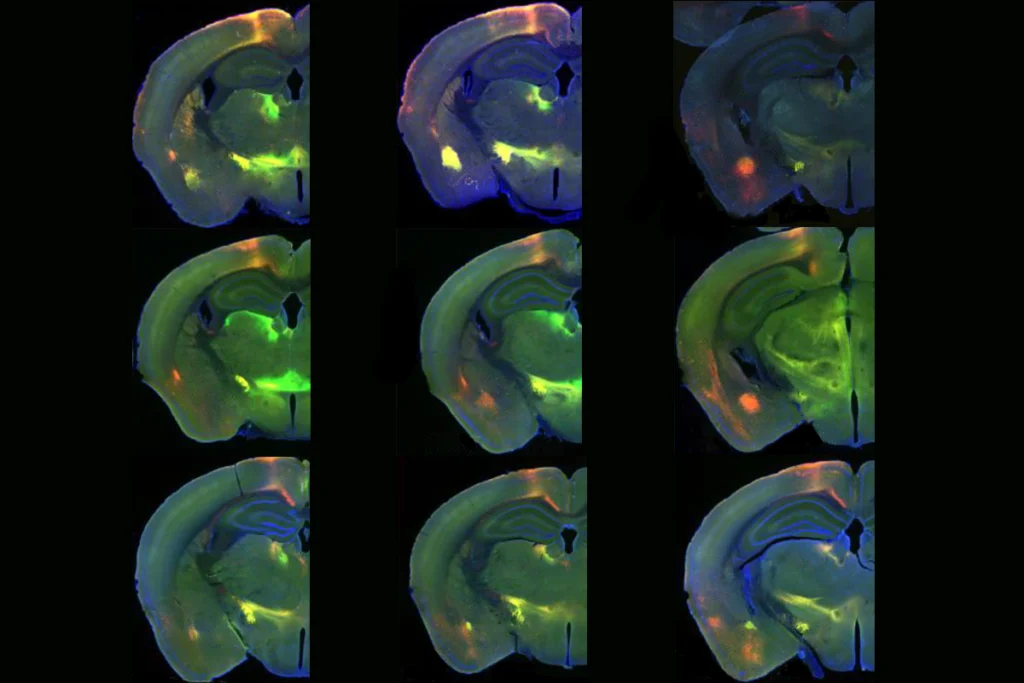

Unraveling schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, autism and so on will likely need to rely more heavily on other methods. They might include human neural organoids to seek cellular and molecular changes, and neuroimaging to seek systems-level perturbations, as well as better biomarkers and identification of specific affected cell types. In the long run, results from these emerging methods could be combined with genetic data to teach us how schizophrenia happens and how to treat it effectively.