Although most autism research focuses on children, it tends to exclude the very youngest. That’s particularly true in imaging studies, for which participants must lie still in a scanner for long periods of time. Enter the international research collaboration Organization for Imaging Genomics in Infancy (ORIGINs). In 2017, the organization began to collect imaging, genetics and behavioral data from 6,809 children aged 6 years and under — including data from about 4,000 of them during their first year of life — from 15 sites in five countries.

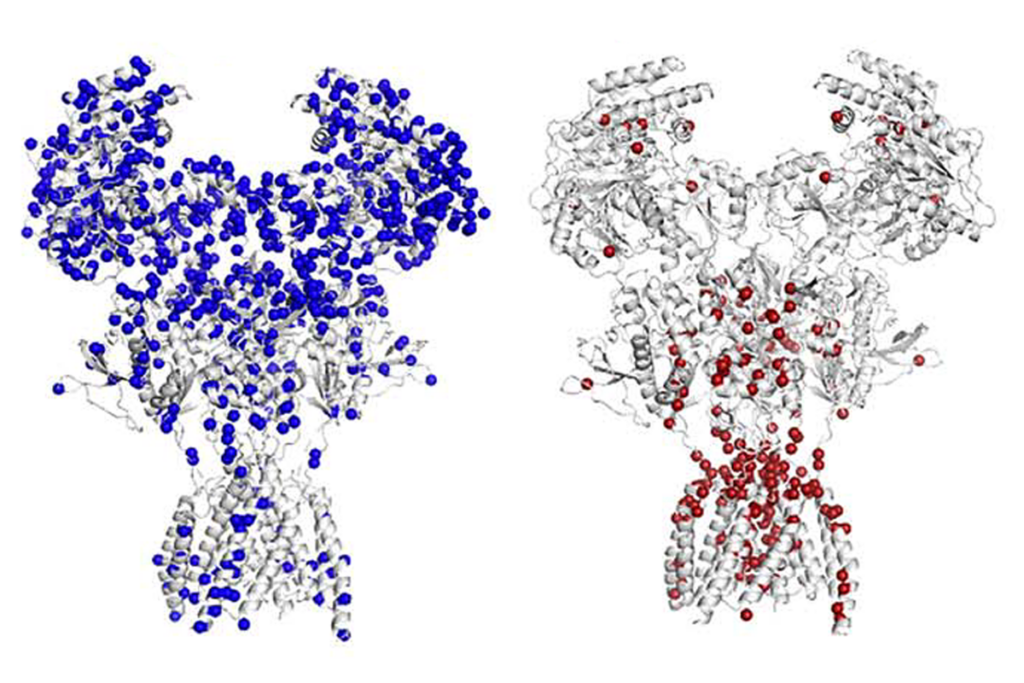

Weaving those disparate data threads together will enable researchers to ask fundamental questions about how the brain develops and how genetic variants associated with brain conditions such as autism affect that process, says ORIGINs founder and director Rebecca Knickmeyer, associate professor of pediatrics at Michigan State University in East Lansing. ORIGINs, an arm of the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta Analysis (ENIGMA) project based at the University of Southern California, is not the first group to take this approach, but it is likely the largest: Imaging genetics studies in infants and young children average just 365 participants, according to a review by Knickmeyer and her colleagues, published in Biological Psychiatry in January.

Spectrum spoke to Knickmeyer about the challenges of imaging babies and young children, and the promise and limitations of identifying neurodevelopmental conditions before age 2.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Spectrum: Why has imaging genetics research focused on adolescents and adults?

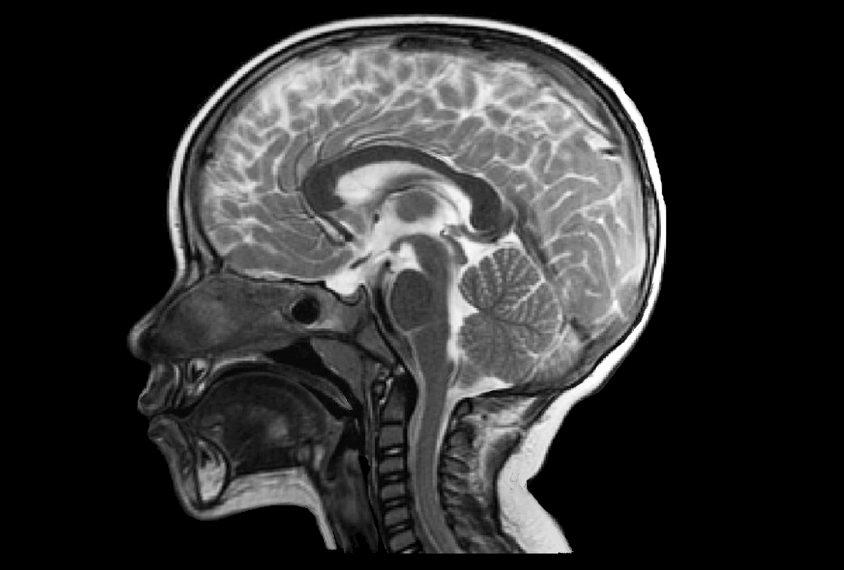

Rebecca Knickmeyer: Scanning young children is super challenging. Small babies are scanned asleep, which is very easy to do, but as they start getting to 1 or 2 years old, it’s a little harder to get them to nap. Once they get to 5 or 6, they’re being scanned awake, so they have to feel comfortable in the scanner environment.

Also, the newborn brain is a lot smaller than the adult brain. It’s shaped differently. The contrast between gray matter and white matter tissues is different. So there are a lot of technical challenges in terms of how you analyze data from infants and young children.