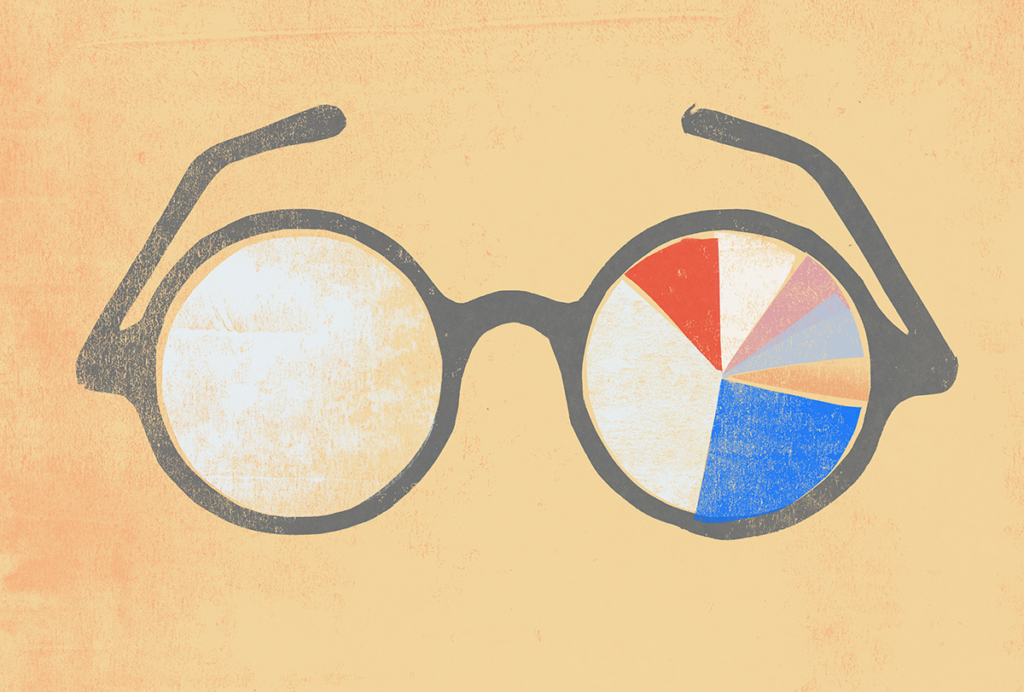

The number of neuroscience-related grants awarded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) has slowed to a trickle during the first two months of the second Trump administration, according to The Transmitter’s analysis of publicly available data from RePORTER, the NIH’s funding tracker.

Since President Donald Trump took office on 20 January, the NIH’s two neuroscience-focused institutes—the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)—have together awarded less than one quarter as many new extramural grants as they did over the same two-month period, on average, from 2016 to 2024. Extramural grant renewals and extensions on existing grants are also down compared with past years.

“This is certainly atypical,” says Joanne Padrón Carney, chief governmental relations officer at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a nonprofit general science organization based in Washington, D.C. “These past two months, the uncertainty, the confusion, has created chaos within the research enterprise.”

Between 20 January and 25 March for the previous nine years, the NINDS and the NIMH awarded an average of 330 new grants totaling an average of $117 million. This year, that number plummeted by 77 percent to just 77 new grants totaling $35 million—a lower award rate than at any point during the first Trump administration.

Between the end of January and the start of April, the NINDS and the NIMH also usually disburse, on average, 100 grants totaling $33 million in competitive grant renewals and revisions, plus about 1,000 grants totaling $455 million for non-competitive grant renewals and extensions. Those numbers, too, have fallen—to 39 grants totaling $8 million and roughly 650 grants totaling $325 million, respectively. The two institutes awarded roughly 9,000 grants totaling $4.5 billion in all of 2024.

“We need to invest in research and in the people doing research, or our public health and our economy will suffer,” Padrón Carney says.

T

he potential reasons behind this year’s funding delays are complex and multifactorial, Padrón Carney adds. For starters, Congress has kept the NIH’s 2025 fiscal year funding at 2024 levels, and the lack of additional funds has likely slowed the pace of new grant awards since last October, the start of this fiscal year, she says.Those delays were exacerbated by the Trump administration’s temporary freeze on NIH communications in January, which blocked the nation’s largest funder of biomedical research from scheduling its grant-review sessions because it could not post the required notices for those meetings in the Federal Register. The stoppage forced the agency to cancel meetings to review thousands of grant applications, NPR reported. NIH study sections, which perform the initial peer review of grant proposals, resumed in late February. But advisory council meetings, which provide a second level of review before funding is awarded, remained on hold until 20 March.

The Trump administration has further rescinded funding from hundreds of grants related to “DEI” (diversity, equity and inclusion) and gender, according to a legal complaint, including those that contain key words such as “diversity,” “equity” and “sex.” But it’s not clear whether new grant applications under review this year were rejected for this same reason, Padrón Carney says.

It’s also unclear if or when the pace of awards will pick back up. “I have every hope that we will see an uptick,” she says. “But we may not see funding at the same level.” A spokesperson at the NIH’s Office of the Director did not respond to a request for comment about the pace of 2025 funding. A spokesperson at the NINDS declined to comment, and the NIMH did not respond to The Transmitter’s request.

The delays have already had a profound effect on scientific research, says Joshua Jacobs, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Columbia University, who studies spatial memory in primates. In anticipation of funding cuts, several universities have announced hiring freezes, and some universities have suspended admission offers for graduate students, leaving a generation of scientists in limbo. “It’s already been very disruptive; people’s careers have already been severely damaged,” he says. Jacobs has yet to receive his non-competing grant extension from the NIH, which he expected in January.

Researchers who study biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia have had to halt years-long longitudinal trials, says Diane Lipscombe, chair of the Society for Neuroscience’s Government and Public Affairs Committee. “You can’t get that data back,” she says. “It’s gone.”