Future of BRAIN Initiative funding remains unclear

As the U.S. Congress begins to discuss federal science funding for 2025, any plans to compensate for this year’s cuts to the neuroscience program face an uphill battle.

Neuroscientists concerned about the fate of the Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative after steep cuts to its funding this year may have a new reason to worry. Last Thursday, Republican members of the House of Representatives passed a bill that proposes a 2.8 percent cut for the National Institute of Mental Health, which helps to fund the BRAIN Initiative, and a 0.2 percent cut for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as a whole for fiscal year 2025.

The 40 percent drop in BRAIN funding in 2024—down from $680 to $402 million—reflected planned decreases to the 21st Century Cures Act, the program’s other key funder; NIH contributions remained stable. For the coming fiscal year, though, Cures Act funding is set to drop again—from $172 million to $91 million—before it expires in 2026. And the proposed NIH budget would make it difficult to compensate for that additional decline.

The Republican bill, which also proposes a significant restructuring of the NIH, is unlikely to become law, members on both sides of the aisle agreed during a subcommittee markup meeting last Thursday. The negotiation process is expected to continue as the bill moves to the full committee markup and then the Senate.

But the political climate it reflects—in which Republicans aim to limit spending—will not make it easy to muster additional funds for the BRAIN Initiative, says Bonnie Watson Coleman, a Democratic congresswoman from New Jersey who serves on the subcommittee.

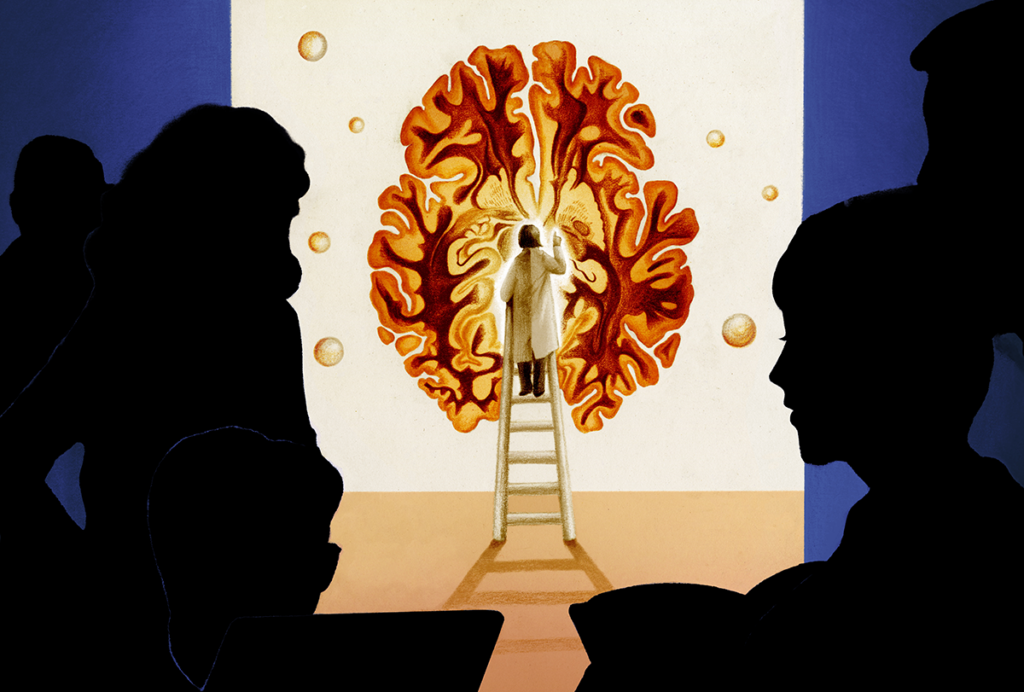

“The BRAIN initiative has enormous momentum, and we are entering a phase where the technologies that are being developed and the discoveries that are being made can plausibly be related to disease—and any delay or reduction in funding will likely further extend the time it will take to find cures for the many neurological and psychological diseases that affect us as humans,” Sandeep Robert Datta, professor of neurobiology at Harvard University, wrote in an email to The Transmitter.

N

IH director Monica Bertagnolli had sought $680.4 million for the BRAIN Initiative in her 2025 budget request, comparable to 2023 funding levels. Such an increase is unlikely, Watson Coleman says. She and her fellow minority subcommittee members are pushing for more spending overall, she adds, but “we don’t think there’s going to be the kind of restoration to the degree we’d like to see.”Because the budget cuts for 2024 happened after that fiscal year began, the program had to cancel eight funding opportunities with 2024 deadlines. The 2025 budget is similarly not set to be finalized until November at the earliest, meaning it will once again be partway through the fiscal year before funding is decided, says Alessandra Zimmermann, budget and policy analyst for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a nonprofit general scientific society based in Washington, D.C.

The BRAIN Initiative has funded 1,575 grants since its launch in 2013. Many of those projects are large and collaborative—and may be difficult to slot in under a different grant program, says Michael Dickinson, professor of bioengineering and aeronautics at the California Institute of Technology.

Nearly 150 concerned scientific organizations, including the Society for Neuroscience and the American Brain Coalition, signed a letter dated 5 June that asks Congress to allocate $740 million for the BRAIN Initiative in the 2025 fiscal year to offset this year’s cuts. Government officials and researchers—including multiple speakers at the 10th annual BRAIN Initiative Conference last month—also continue to speak out about the importance of keeping their work funded.

“I am especially invested in reaching out to both sides of the aisle, as the issues we are really talking about here—understanding how the brain works and using that understanding to prevent or treat human disease—affect all citizens regardless of their politics,” added Datta, who spoke at the meeting.

Researchers who are interested in sharing their own thoughts with Congress can use the Society for Neuroscience’s advocacy page to find and contact their representatives.

Recommended reading

NIH cuts quash $323 million for neuroscience research and training

Multisite connectome teams lose federal funding as result of Harvard cuts

Neuroscience needs to empower early-career researchers, not fund moon shots

Explore more from The Transmitter

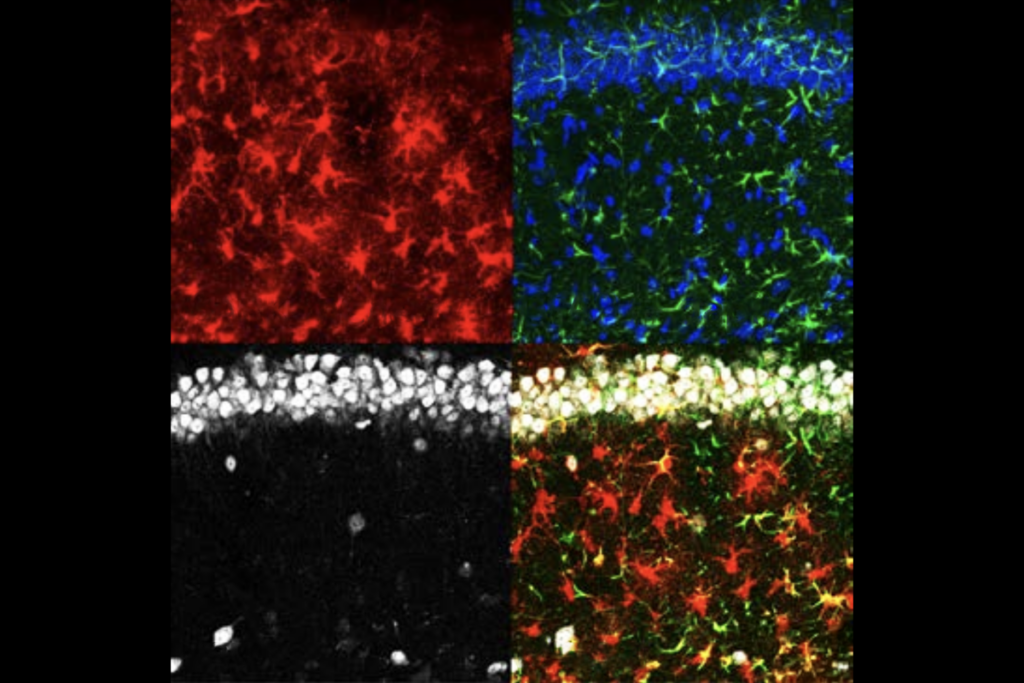

Astrocytes sense neuromodulators to orchestrate neuronal activity and shape behavior

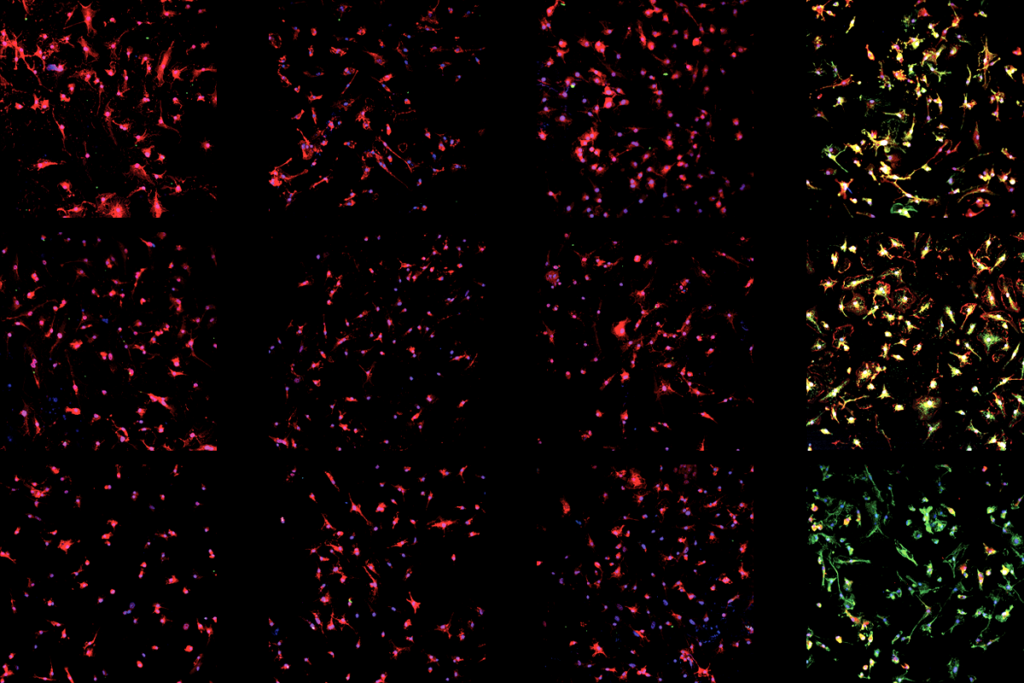

Authors correct image errors in Neuron paper that challenged microglia-to-neuron conversion