Most people visit the Minnesota State Fair for a fun-filled day of fried food, farm animals and carnival rides. Not Ka Ip. He saw the annual event as the perfect setting for a new experiment.

Ip, assistant professor of child development at the University of Minnesota, is particularly interested in executive function: the set of skills, such as organization and impulse control, people need to plan and achieve goals. Children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to perform worse on tests of these skills than do their more privileged peers, past research shows. But that gap may reflect where those skills are typically tested: a quiet lab, in which some children may feel out of their element, Ip says. “That may not actually mimic their actual day-to-day environment.”

Which is why Ip started to devise a series of experiments to conduct at the less-than-serene state fair. “We really want to understand how, for example, unpredictability in the home environment is related to executive function development,” he says. The fair also offered a way to recruit children from a wider swath of society than researchers can often find at a university, he adds.

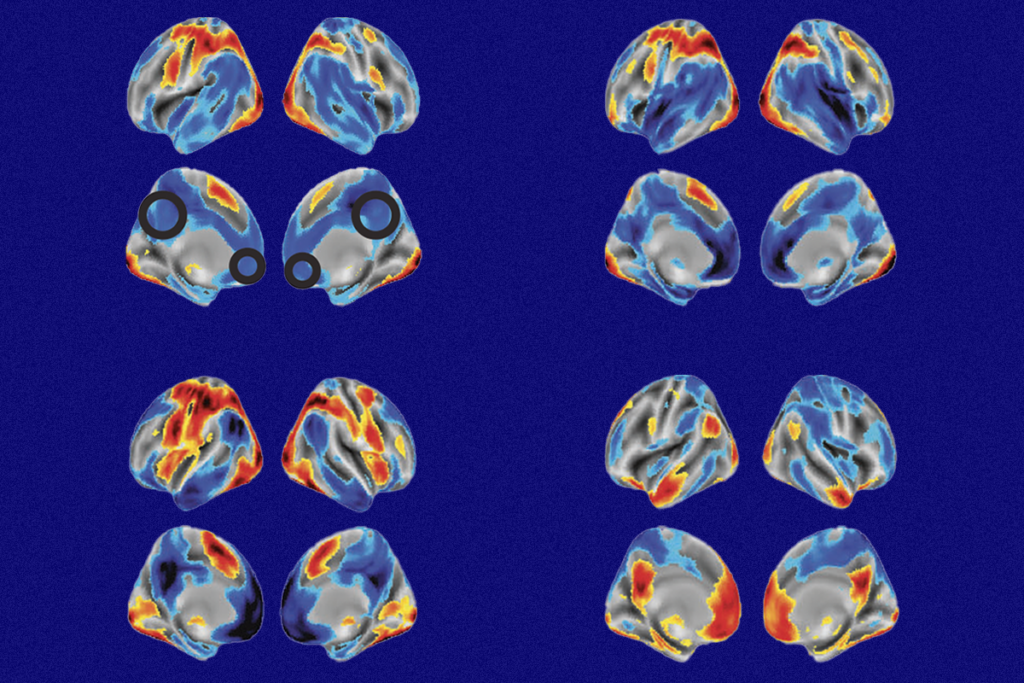

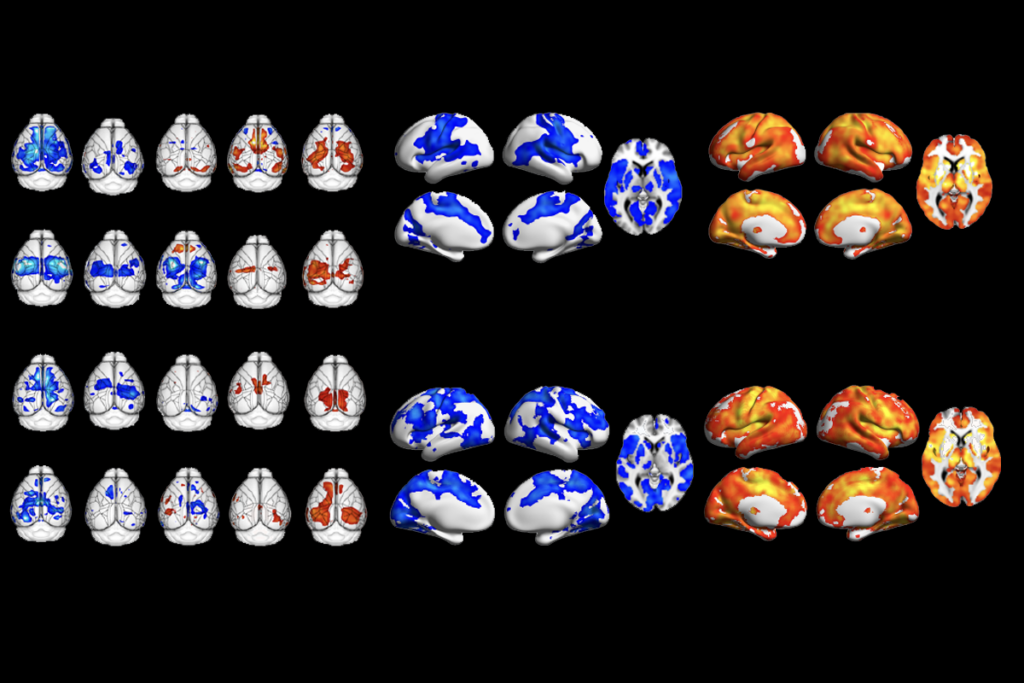

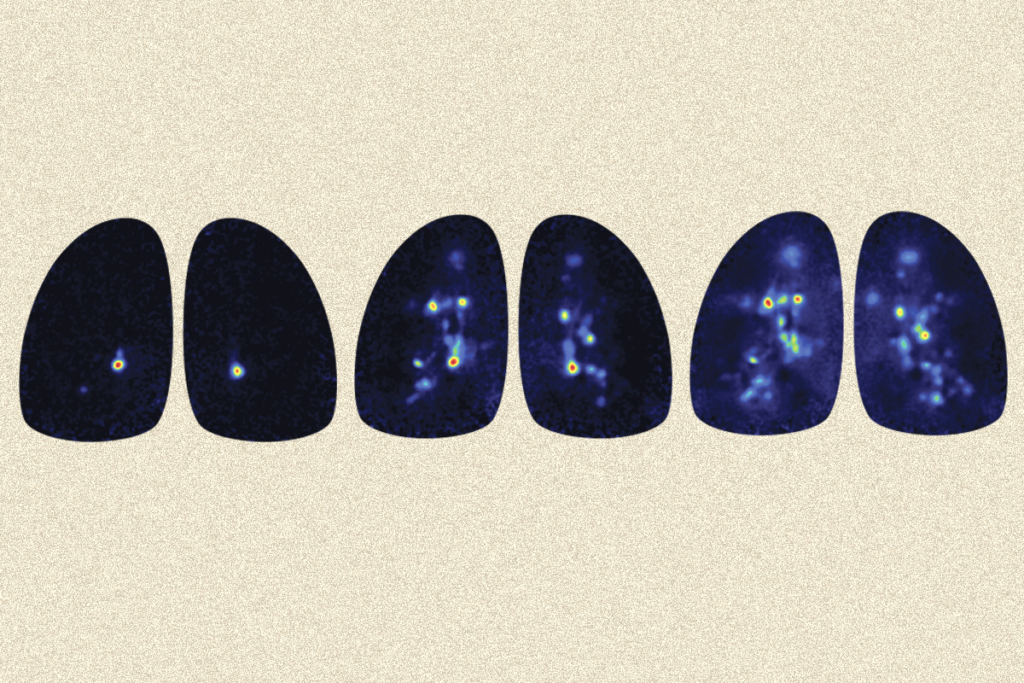

Last month, after a year of planning, Ip and his team lugged a trolley full of equipment to the fairgrounds outside Minneapolis. There, they collected functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) data on 75 children aged 3 to 7 as they played a computer game that tests impulse control. The team aims to evaluate whether the bustling surroundings affect participants’ performances and neural activity differently based on their background.

Ip spoke with The Transmitter about why he is focused on moving his research out of the lab, the challenges—and advantages—that come with running an experiment in an uncontrolled setting, and how pickle pizza helped him recruit participants.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: Why were you interested in moving this test of executive function out of the lab?

Ka Ip: A lot of these tasks are really boring, and they’re often tested in environments, such as a lab, that are completely silent. The kids have to sit at the computer screen with no distractions whatsoever and still be able to perform. In a typical school environment, there are a lot of things going on, a lot of different distractions. So we’re not really mimicking how kids learn in a day-to-day environment when we test these things in such a controlled setting.

TT: What is known about how executive function develops?

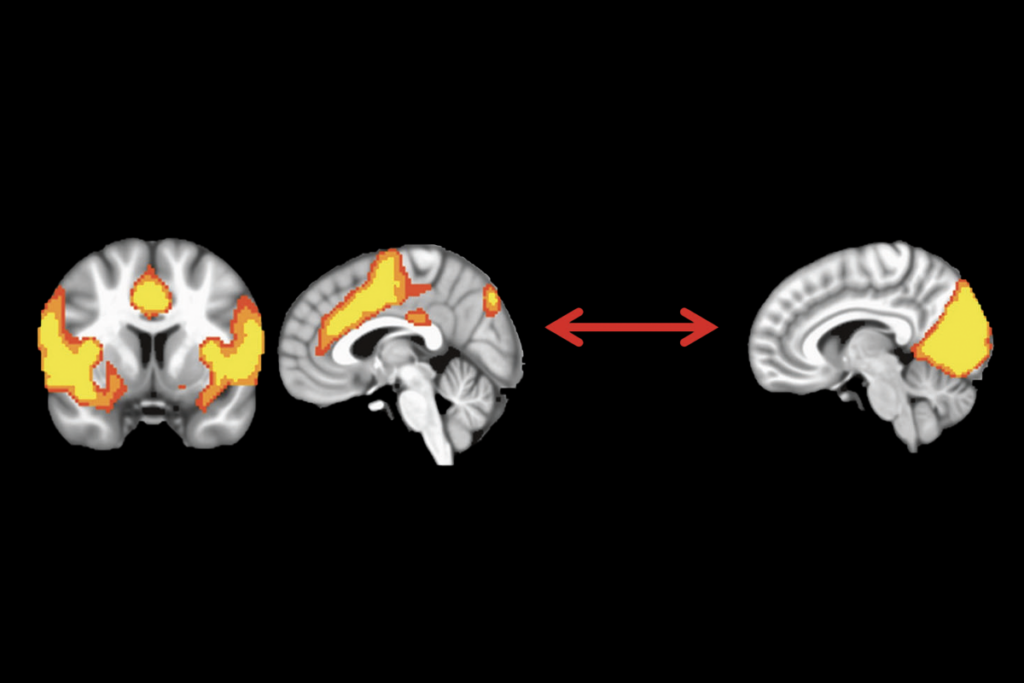

KI: Not much. Most of the studies that focus on executive function development are on preschoolers or much older children. We know the specific brain regions that are involved in executive function, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. But we don’t really know how that changes with the environment.

TT: How did you get involved in the fair?

KI: I went to the state fair last year, and I discovered that there’s a building there for doing research. When I saw that, I was like, “Man, I’ve got to get into this next year to do research in the wild!”

We started off by trying to collect data at the Minnesota Children’s Museum through weekend outreach. One of the cool things with this fNIRS device is that you can see the brain’s activity in real time. When neurons are really active, they dilate nearby blood vessels and increase oxygen levels there. Oxygenated blood absorbs infrared light differently than does nonoxygenated blood, so you can infer activity from the tissue’s optical properties. You can actually show the parents and the kids what a person’s brain activity looks like while they’re doing a task, and so we became pretty popular at the museum for that. And learning from that experience over the past year, we felt ready to try it out at the fair, so we had a booth.

We want a diverse sample in terms of racial, ethnic and socioeconomic background, and we see that at the fairgrounds. At a state fair, everybody comes. And a lot of families are not the typical demographics that you’re able to recruit on a college campus, for example.

TT: What kind of data did you collect at the fair?

KI: The kids are mostly looking at a computer screen while wearing an fNIRS cap. They can see other things surrounding them, but they’re facing away from most of it. We were fortunate to be able to adapt a task from Susan Pearlman’s lab at Washington University in Saint Louis. It’s a child-friendly Stroop task called a Pet Store Stroop Task. The children see one animal, but they hear a different one. So, for example, they’ll hear a cat and see a dog photo. They have to ignore the picture and pay attention to the sound—so they have to put the animal into the cat house instead of the doghouse. We tell them that the animal likes to pretend to be a cat. It’s quite a fun game; our kids love it.

In addition, we also administer a standardized cognitive battery called the NIH Toolbox, from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. That gives us information on vocabulary development as well as cognitive flexibility. And the parents fill out questionnaires about their home and neighborhood environment.

TT: What are some of the challenges you’ve encountered with this setup?

KI: There’s less environmental control than there is in the lab. Sometimes the technology may not work, and we have to find a way to troubleshoot it quickly. I remember one of the times—even though our fNIRS device doesn’t need Wi-Fi, we still used a hot spot to magnify the signal. We had put it on the ground to make sure that nobody would touch it. But we didn’t know that the metal table that we were provided at the fair actually blocked some of this signal!

And there are other challenges. Kids will just run into our booth. And parents really want to take pictures. So we have ways of managing that. Even though we’re doing this in the wild, and we want some of this activity, the kids still have to have an environment in which they can do the task. That’s also forced us to come up with a task that can engage kids well.

TT: Have you had any other surprises, running your experiments in such an unusual place?

KI: One of the more popular foods at the fair this year was pickle pizza, and the line ran in front of our booth. So we would talk to parents while they’re waiting in line, like, “Would you and your kids be interested in doing a study while you’re waiting there for 30 minutes? Might as well.”

TT: You never know where you’re going to get your next participants.

KI: You never know.