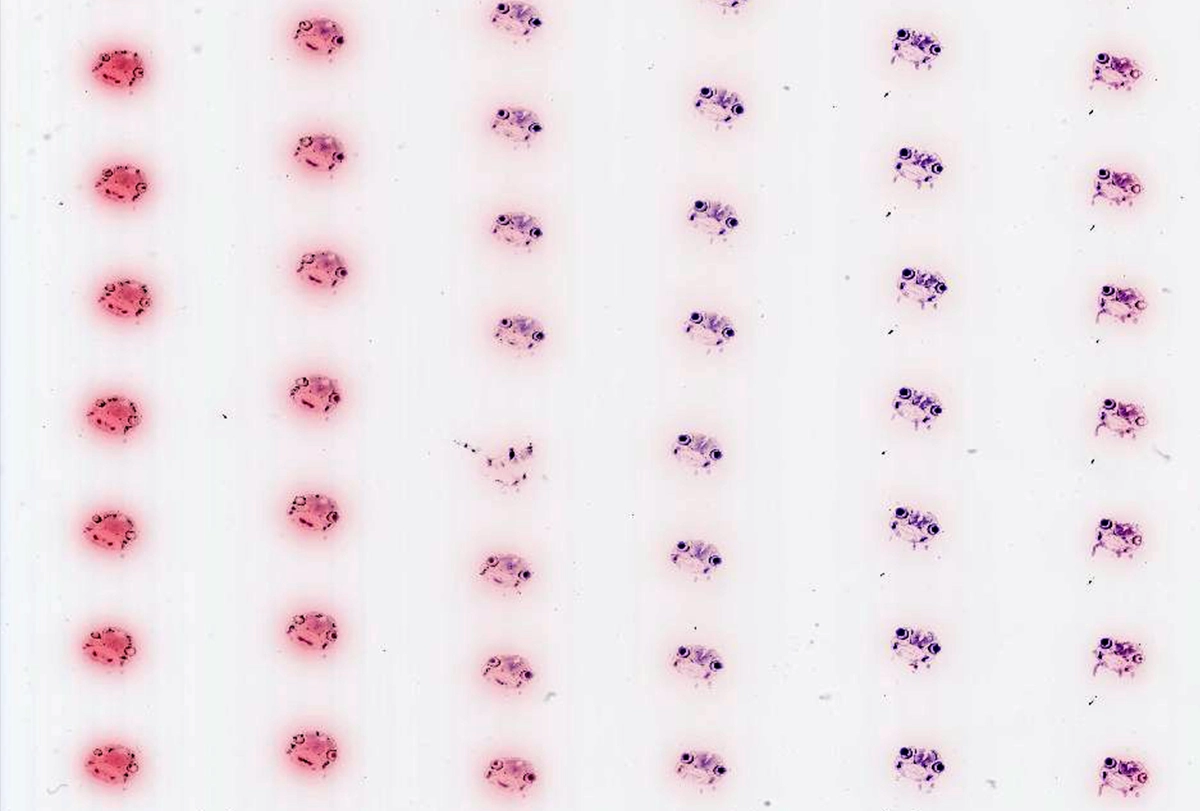

For evolutionary neuroanatomists who compare diverse animal brains, access to a gold mine of 500,000 histological sections and whole mounts is now only a mouse-click away.

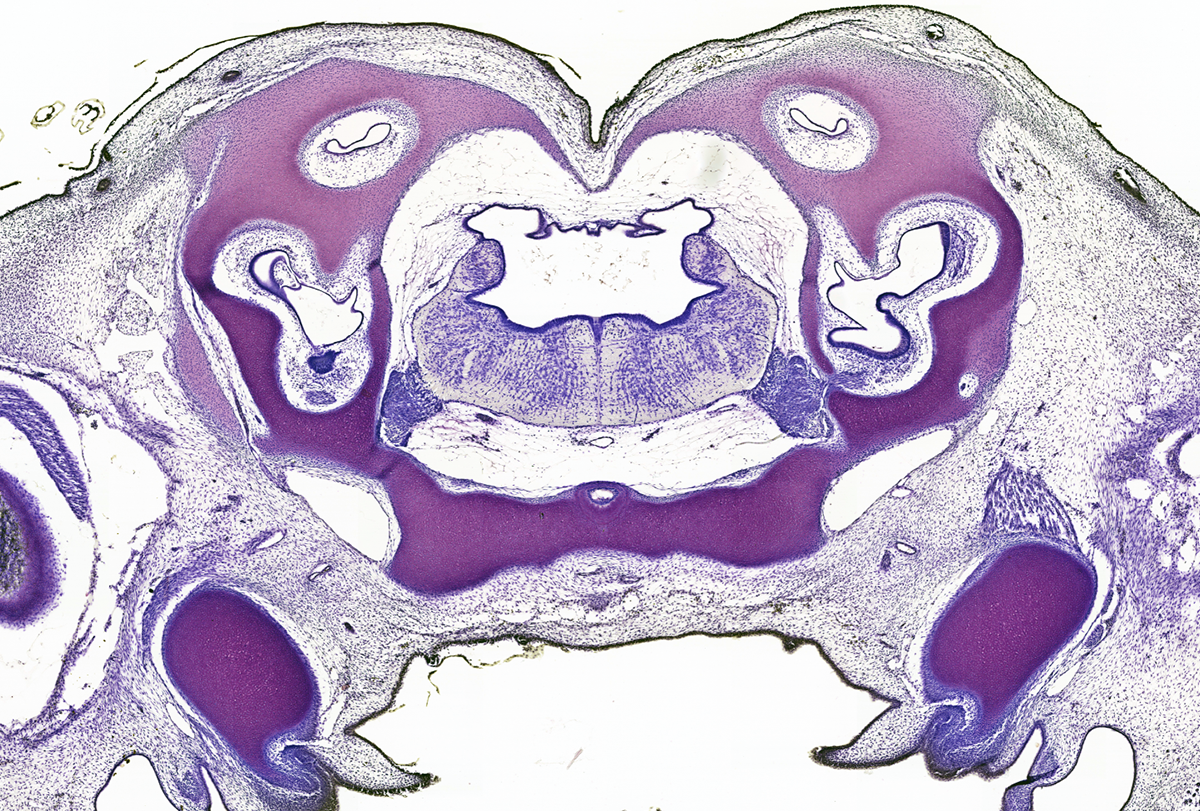

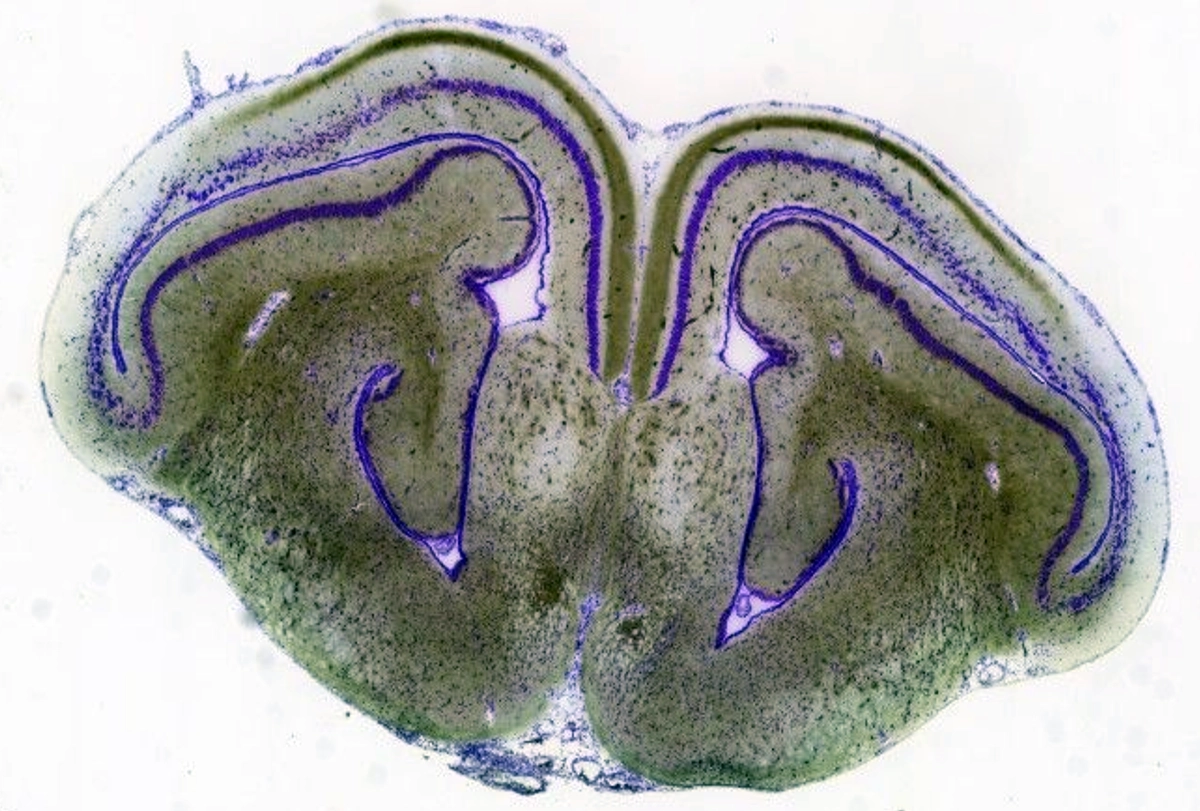

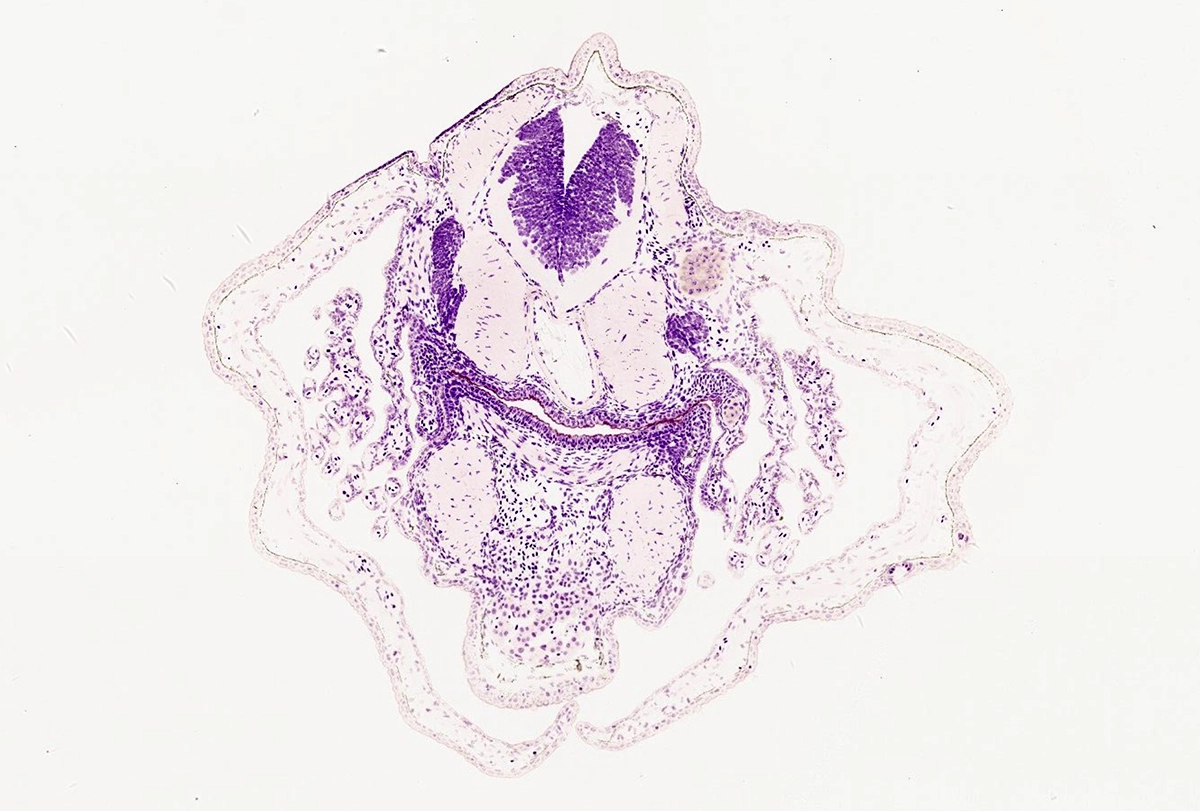

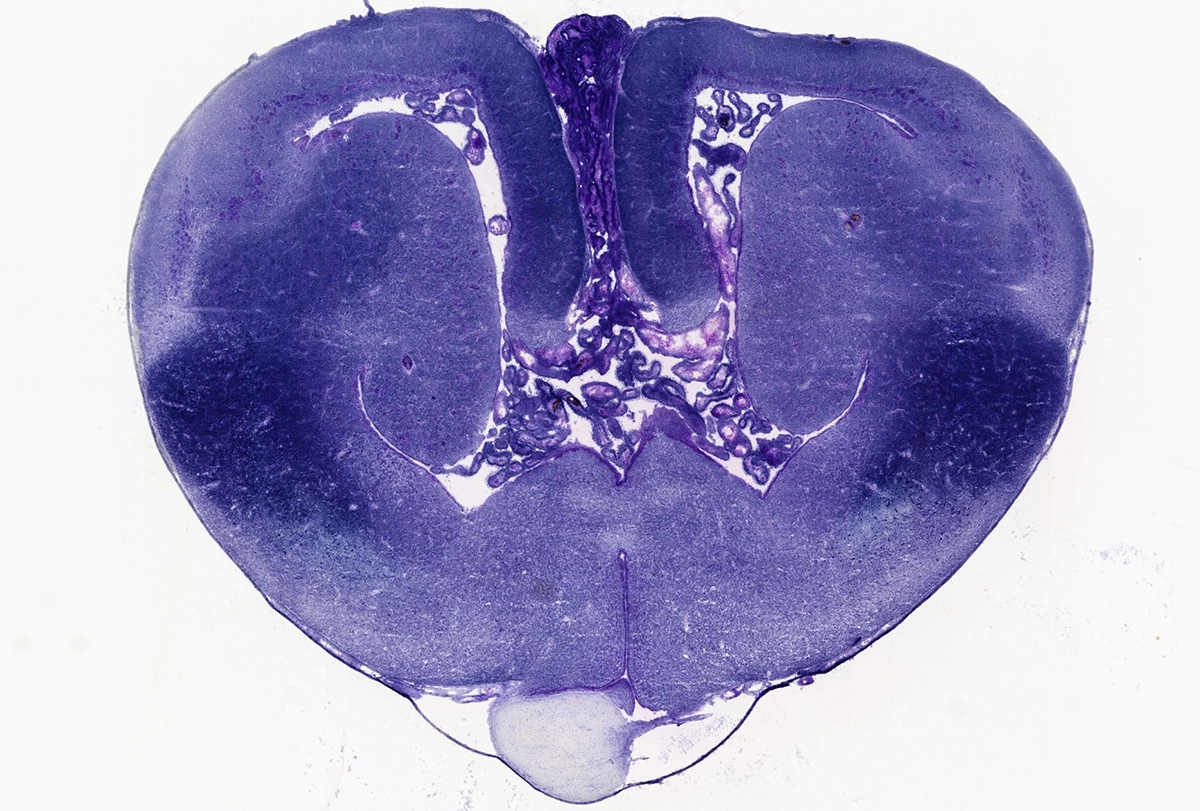

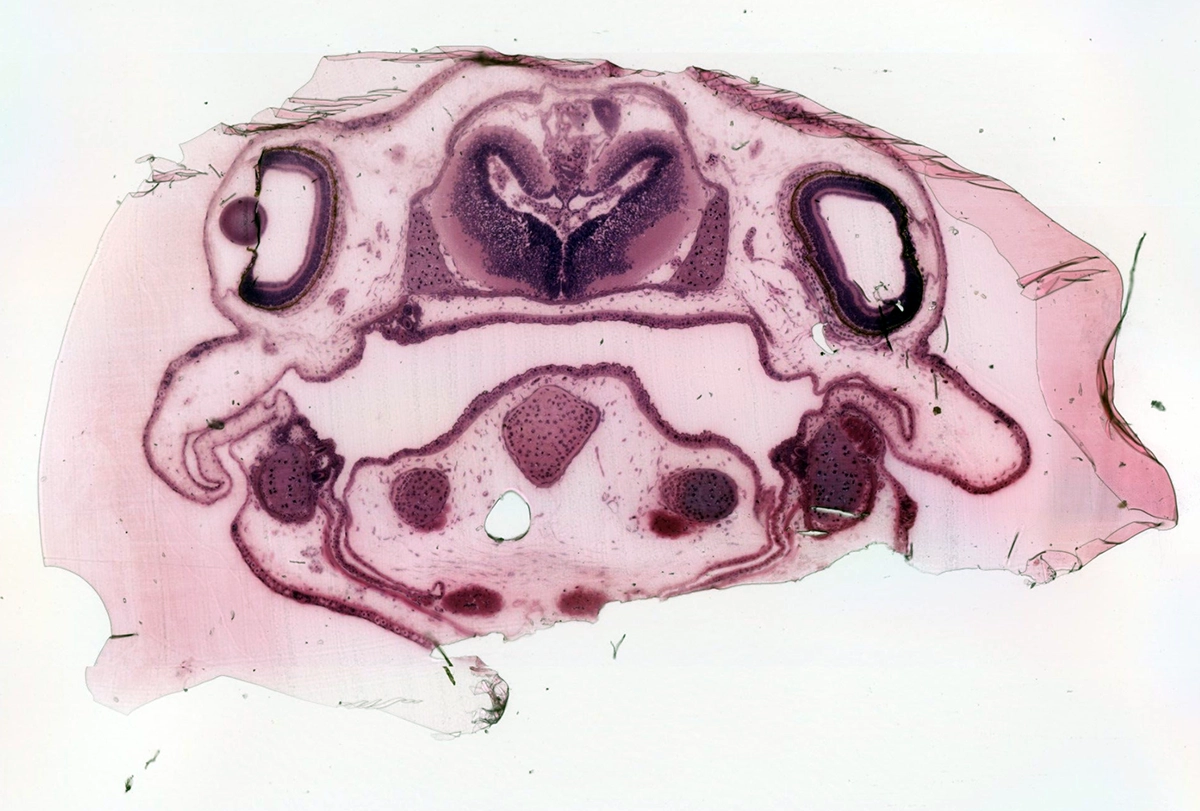

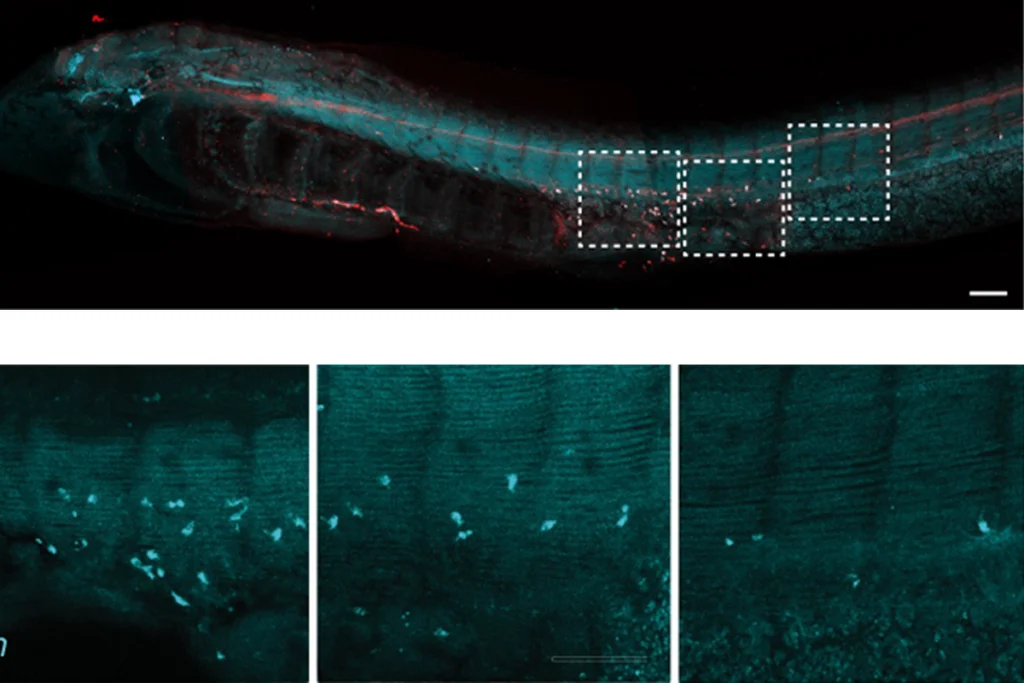

The R. Glenn Northcutt Collection of Comparative Vertebrate Neuroanatomy and Embryology at Harvard University—which comprises 33,000 slides of tissue samples from more than 240 vertebrate genera—is one of the world’s largest and most diverse collections of its kind. Northcutt, a prolific comparative vertebrate neuroanatomist and emeritus professor of neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego, amassed the collection over the course of five decades. Since 2021, James Hanken, research professor of biology at Harvard University and curator at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, has led an effort to digitize it.

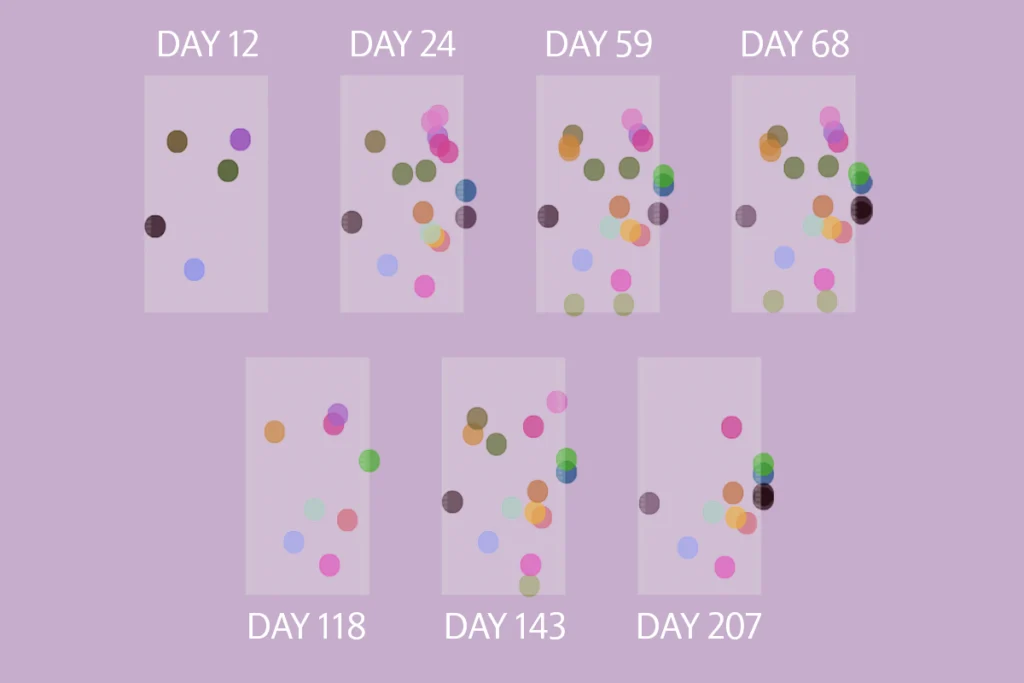

The scanning process is still ongoing and may take another two years to complete, Hanken says, but more than 8,000 slides are already publicly available in two online data repositories: MCZBase and MorphoSource.

A comprehensive inventory of the entire collection appears in a paper Hanken and his colleagues published last week in the Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. It provides researchers with an in-depth guide for using the collection, Hanken says.

Few other resources of this type are available online to researchers interested in evolutionary biology and brain anatomy, says Andrew Iwaniuk, professor of neuroscience at the University of Lethbridge. For example, neither the Welker Comparative Anatomy Collection nor the Starr Collection, both housed at the U.S. National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland, are available online. To access slide collections such as these, scientists have had to travel to see them in person, which can be difficult for those outside the United States, Iwaniuk adds.

“These days, there’s more and more people [who] are interested in these big evolutionary questions when it comes to the nervous system,” he says. “Those sorts of questions can really only be best answered by having these broad comparative anatomical collections that take a lifetime to assemble.”