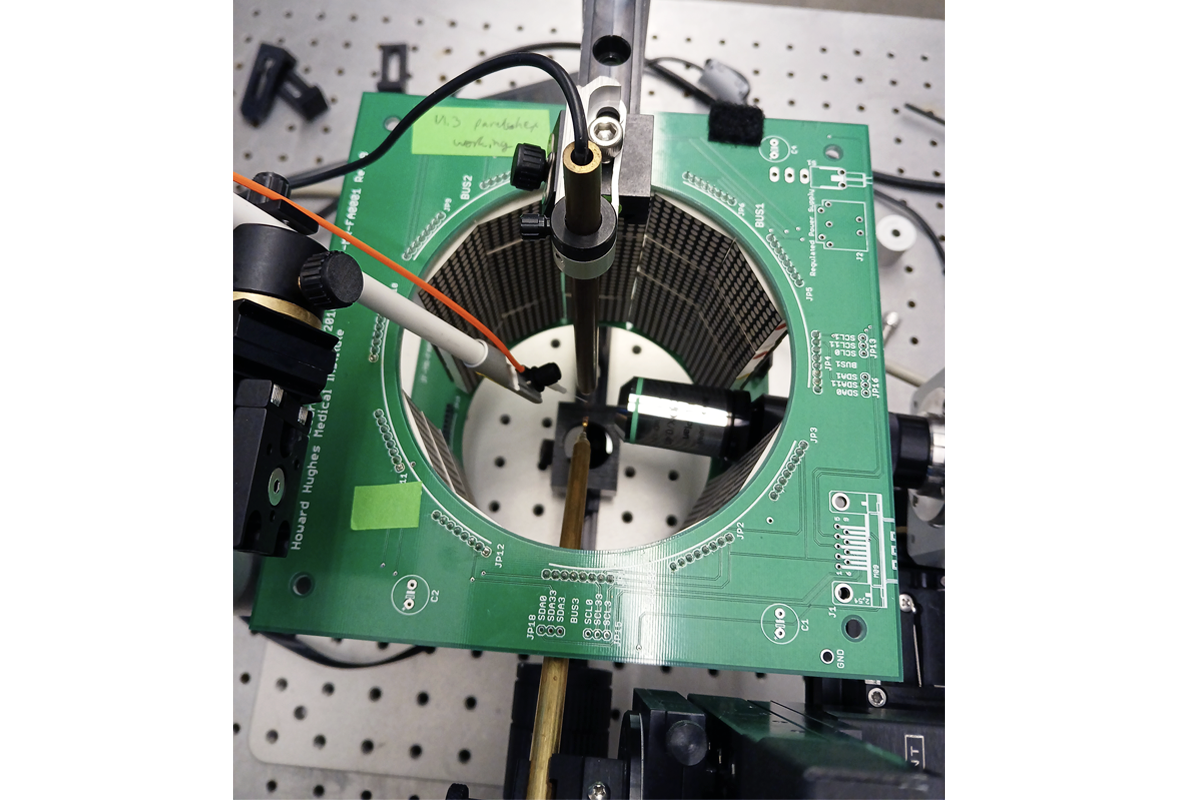

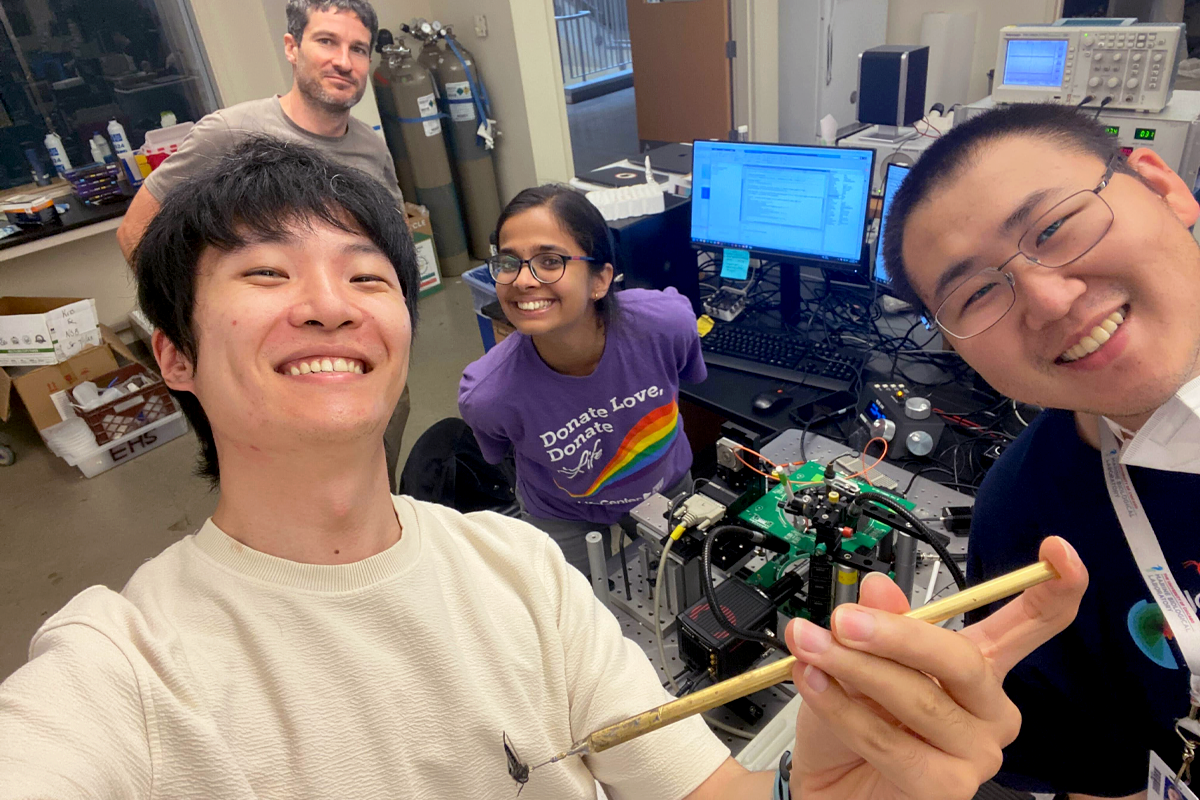

On a muggy July evening in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, as vacationers lounged on nearby beaches, a group of scientists clustered around a solitary fruit fly suspended in a virtual reality flight simulator. The scientists flicked a switch to bathe the tethered fly in spooky red light. Almost immediately, the fly’s wingbeat frequency began to plummet. The fruit fly had been genetically engineered to express a light-gated ion channel in the motor neurons controlling its respiratory system, enabling the scientists to optogenetically cut off the oxygen supply to the insect’s muscles and brain.

Playing through a speaker hooked up to an optical wingbeat analyzer, the peppy whine of the fly’s wings deepened to a weary drone … 200 hertz … 180 … 160. Suddenly, the din cut to silence as the fly ceased to beat its wings. At that moment, the seed of a scientific factoid was born: A fruit fly can sustain flight while holding its breath for less than three seconds. The scientists hooted with the thrill of discovery and immediately prepared another fly to repeat the experiment.

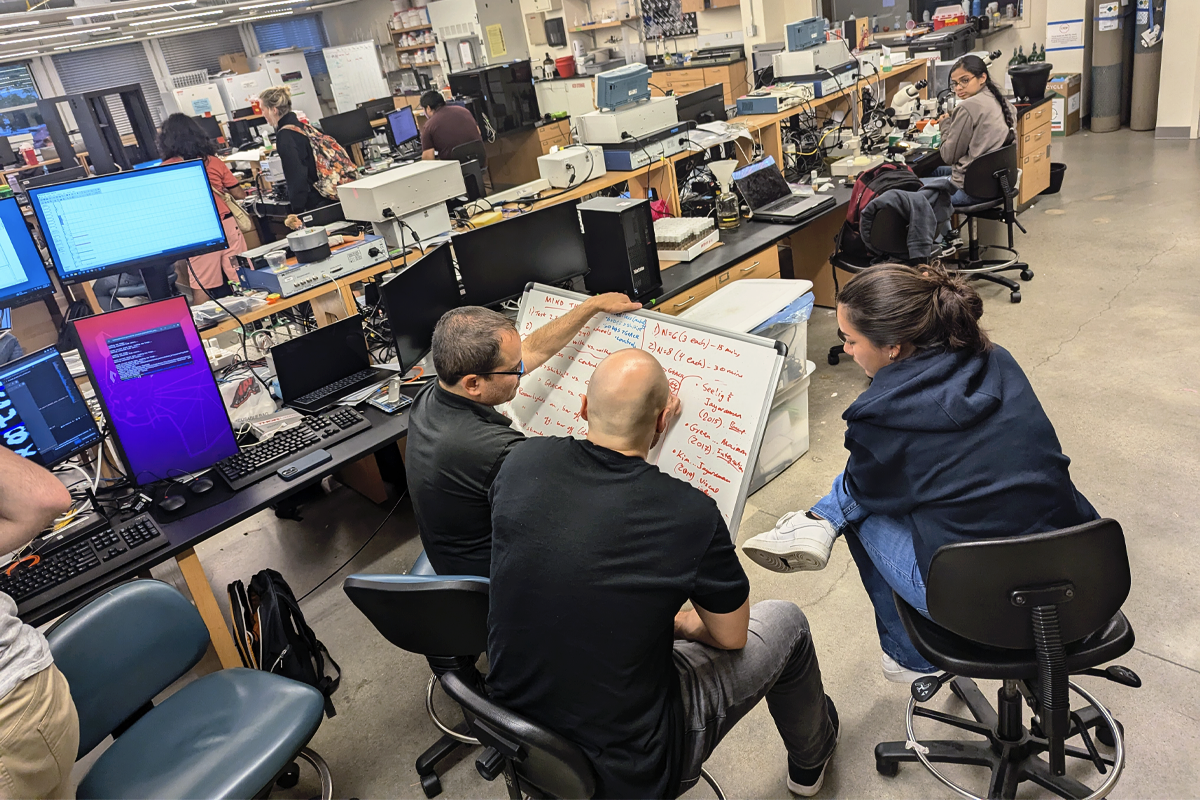

I witnessed this particular experiment as an instructor in the Neural Systems & Behavior (NS&B) summer course at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), a center for biological research and education in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. MBL has been hosting courses for more than century, a vibrant tradition that has spread to other institutions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory offers courses on a range of neuroscience techniques; the Allen Institute and the University of Washington jointly host the Dynamic Brain workshop at Friday Harbor Laboratories; and the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics hosts rotating neuroscience courses at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Neuroscience summer courses outside the United States include the Cajal courses in Europe; the Riken CBS Summer Program in Japan; CAMP@Bangalore in India; and the Small Brains, Big Ideas course in Chile.

Access to hands-on training courses has also recently expanded to traditionally neglected regions of the global South because of the efforts of organizations such as Teaching and Research in Natural Sciences for Development in Africa and the International Brain Research Organization. During the COVID-19 pandemic, access to intensive summer courses was expanded even further through the creation of an online computational summer course, Neuromatch Academy.

These kinds of courses provide a structured environment for students and instructors to focus on the most basic and joyful aspects of being a scientist. The courses offer graduate students and postdoctoral researchers exposure to a breadth of scientific ideas, teach new technical skills and forge new relationships in the fire of collaborative scientific endeavor. For faculty like me, these courses deliver sublime moments of discovery that reconnect us to why we became scientists in the first place. Like a washed-up sports hero rediscovering his love of the game by coaching a team of underdogs to victory, I always return home from the course physically exhausted but intellectually invigorated and reinspired.