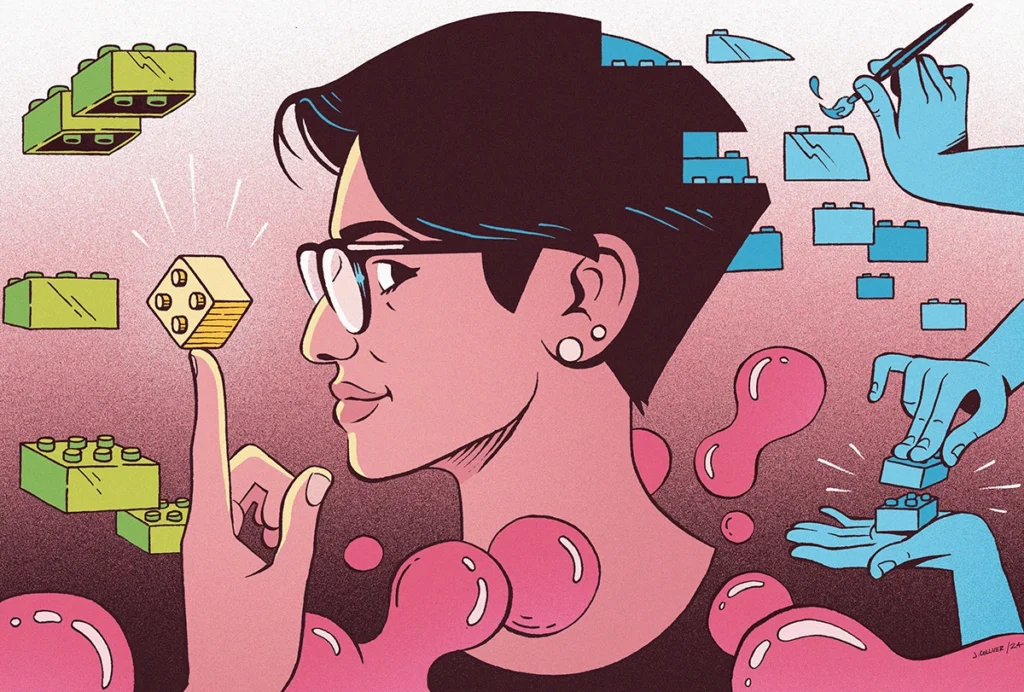

I am a compulsive collaborator. I love seeing how people with different backgrounds think about neuroscience. More than 90 percent of what our lab has published has involved some form of collaboration, whether it be with another group at our institution or colleagues from far-flung locations.

Good collaborations are force multipliers. They extend a study’s scope, enable you to ask research questions in creative ways, and add rigor by testing hypotheses from multiple angles. That’s especially true in modern neuroscience, which often requires wide-ranging expertise. Collaborations are, quite simply, one of the best parts of doing science.

But how do you go about determining who to work with? What makes for a good collaborative colleague? Figuring out how to choose collaborations, how to manage them and which collaborations to avoid is essential for early-career scientists. Here I share some concrete tips to do just that.

G

ood collaborators give the relationship care and attention from the start. If it goes well, you’ll be spending a lot of time with each other, doing experiments and writing papers and grants. You need to be able to trust each other to get things done in a way that makes everyone happy. One of the nicest compliments I’ve ever received was at the beginning of a project with someone who is now one of my closest collaborators. They said that it was a joy to see each version of the grant improve with my input. I felt the same about how theirs improved my writing. A colleague who cares enough to help you improve your own work is the type of person you want to work with. Cultivate that relationship; it can only pay dividends.You also need to find someone you can communicate with clearly, and vice versa. This is particularly important in neuroscience collaborations, which bring together people from different subfields who use different types of tools and techniques. As an expert in electrophysiology, I must clearly explain the nuances of my experiments—especially what they can and cannot tell us—to my neuroscience colleagues who have other areas of expertise. And I need my collaborators to be able to explain their techniques—say, a molecular biology method that seems inscrutable to me—so that I can understand how my data fit in the broader context of the project.

I’ve found that some of my best collaborations have been with people at a similar career stage. Beyond the core science, you can serve as each other’s cheerleaders and mentors, finding ways to best navigate the ivory tower together. You might even find someone who understands the references you make to movies from the ’80s. I’m happy to say I have that part going for me, which is nice.

But that doesn’t mean you should work exclusively with people at a similar career stage. Far from it. When you’re just starting, a good collaboration with more senior colleagues can have a significant impact on your career. That said, managing relationships with senior colleagues can be complicated when you’re a freshly minted assistant professor. You were hired, in part, because your research complemented the expertise and interests of your new department and community. It’s no surprise that senior people would want to collaborate with you. But it is important to be selective at this stage.

For instance, you might need to be careful if someone wants to add you as a co-investigator to their grant. It sounds lovely, but such actions can have unexpected negative consequences. If you’re part of the U.S. system and have yet to land your first big grant from the National Institutes of Health, you are classified as an early-stage investigator. This early-career status often doubles the chances of getting your first major grant (R01) funded. But you lose this designation if you get a grant co-authored with an established investigator. There are ways to avoid this, but you need to work together with your senior colleague to submit a grant application that allows you to keep your early-stage status.

To add to this, beware the elder statesperson who asks you to do something because “it’d be great for your career.” You might feel flattered, thinking, “Dr. So-and-So wants to work with me?” But the truth might be more insidious. Ask yourself why they are approaching you. Is there anyone else nearby with a similar skill set? Why weren’t they asked instead? Is this a necessary experiment, or are they looking to add a flashy new technique so they can boast about “innovation” in the grant application?

The fact is, they may be turning to you because they’ve burned all other bridges. Look at their publications and grants to see if they work with others, and for how long. Talk to someone they’ve collaborated with in the past and ask what those people thought of the experience. Are they the type of person who takes care of junior colleagues, or do they view them as cogs that help advance their own career? Are they generous with placement on author lists, co-authorship status and financial support, or do they hoard those spoils for their own benefit?

I

f a proposed collaboration raises your hackles, the easiest thing to say is that you’re too busy. But if you’re like most academics and have a hard time saying no, at the very least try to be selfish. If it is a collaboration in which you’re largely helping someone else, ask yourself if it’s really worth it. Try to estimate the time it would take you to do the experiments. Now triple that and ask yourself again if it’s worth it (because, in truth, that’s how long it will likely take).If the answer is no, ask yourself what would make it worth it. Is this something that you could pilot yourself in a short amount of time to confirm if it’s worth pursuing? If it is, are you willing to train someone from their lab to follow up? Is your collaborator willing to devote time and energy to learning new techniques, or do they just want your results? If you’re in a position where it does make sense to have such a project funded by a grant, are they willing to do some heavy lifting in that department? How people approach these questions tells me what kind of long-term collaborator they might be. If they say and do what you would do yourself, it’s likely worth your time.

The projects in which you’re both invested in the same questions can be career-altering. But even the projects that initially feel like you’re mainly aiding someone else can ultimately force you to think about something new, helping you grow your own interests.

In short, approach collaborations with enthusiasm and educated caution. Be sure to watch out for yourself and your team so that everyone is rewarded properly for their efforts, especially when you’re just starting your lab. Once you have that covered, go find yourself a collaboration or 2—or 12.