This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: How did you become interested in incorporating comics into science?

Kanaka Rajan: I had two points of entry: One is that I sketch a lot. I think everything is interesting once you draw it; it helps your brain process things.

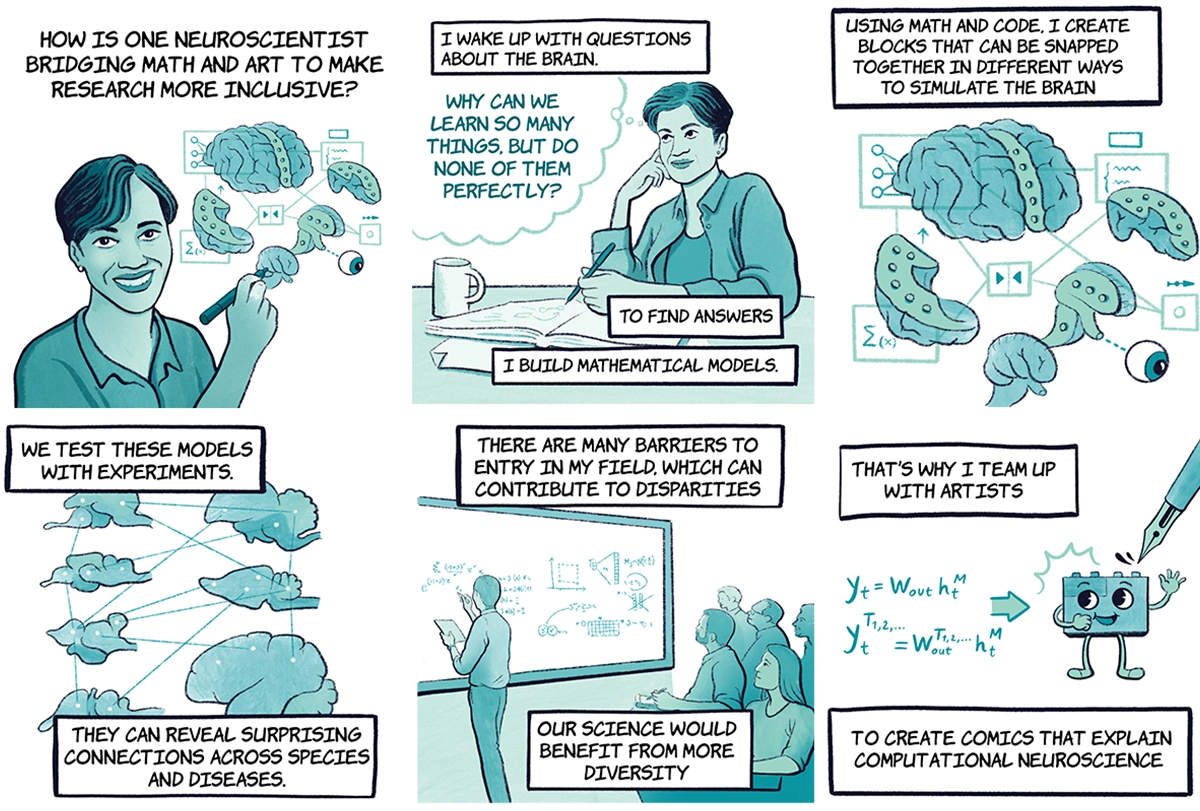

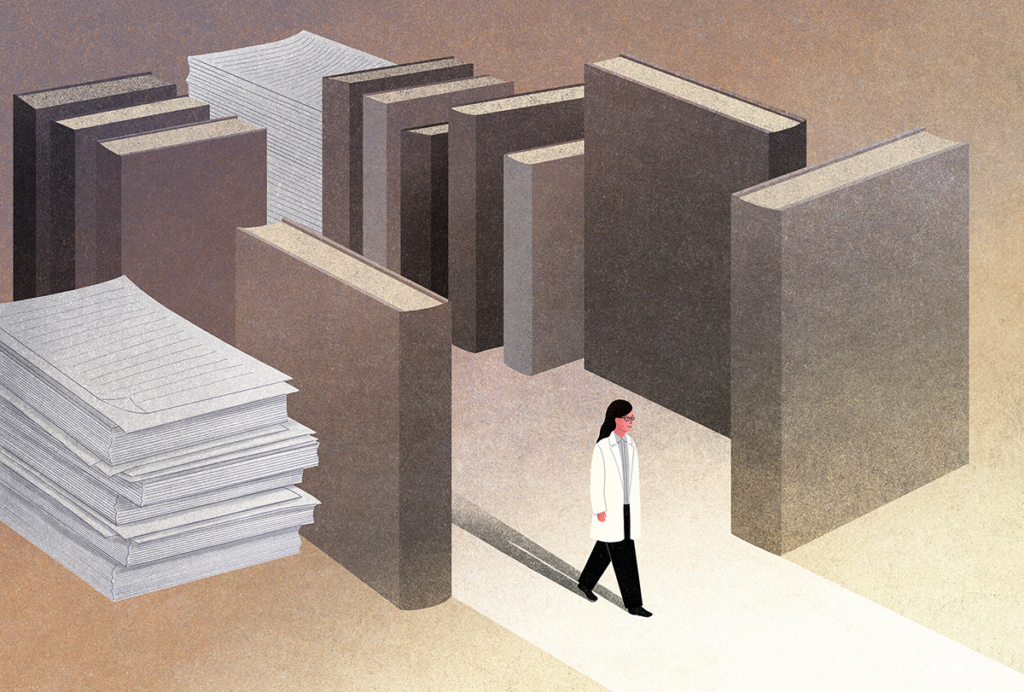

The other point was realizing that scientific papers are kind of an awful medium. They’re incomprehensible. It’s kind of a secret form of gatekeeping. As if we keep our science special sounding, then it will attract only the luminous geniuses. That thinking has led to several problems in the field that diversity, equity and inclusion efforts alone will not be able to solve. The pipeline is leaky everywhere.

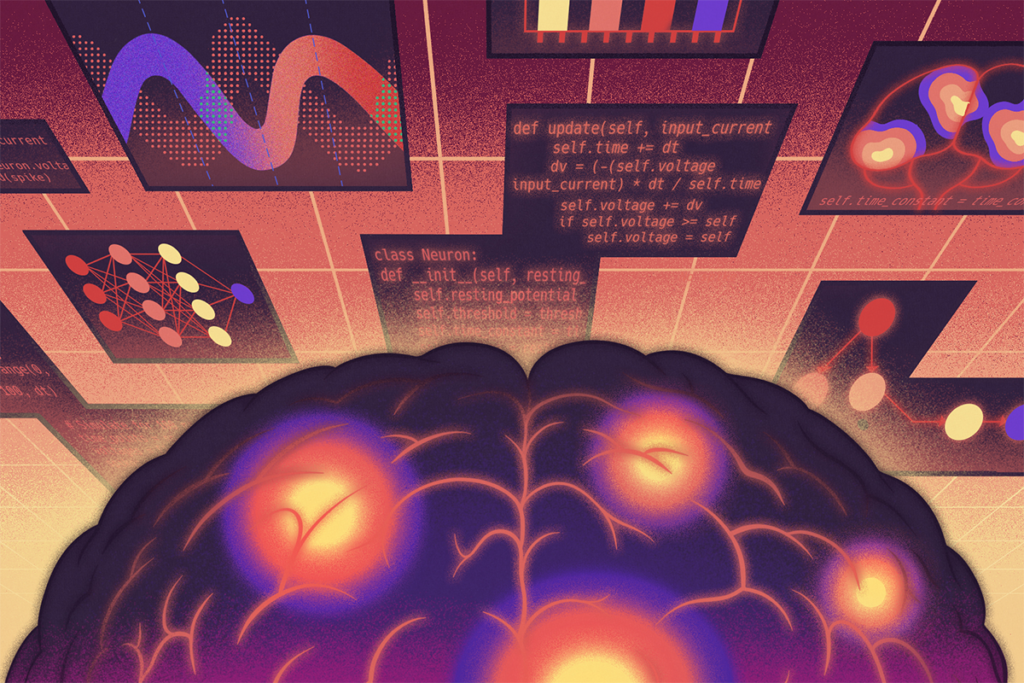

So one of the concrete things is to democratize access to the information in my papers. The content in it is not 200 years of physics you have to learn. It’s high school linear algebra for the most part. It’s programming, which pretty much every high school student can do. A dedicated high school student or an undergrad can ramp up to a research problem very fast.

TT: Why are comics effective at lowering some of those barriers to entry in neuroscience?

KR: In making comics, we’re not diluting the content. We’re just removing jargon from it. We’re democratizing access to it, and we’re turning technical details into schematics and graphics. That’s it.

We’re not stupidifying the work. I’m making it visually engaging without jargon. We’re saying, “Come play with us; the sandbox is open.” We’re not saying, “We’re luminous geniuses and we have special sand.”

TT: Do you have an example of when working with a comic illustrator helped make your work more accessible?

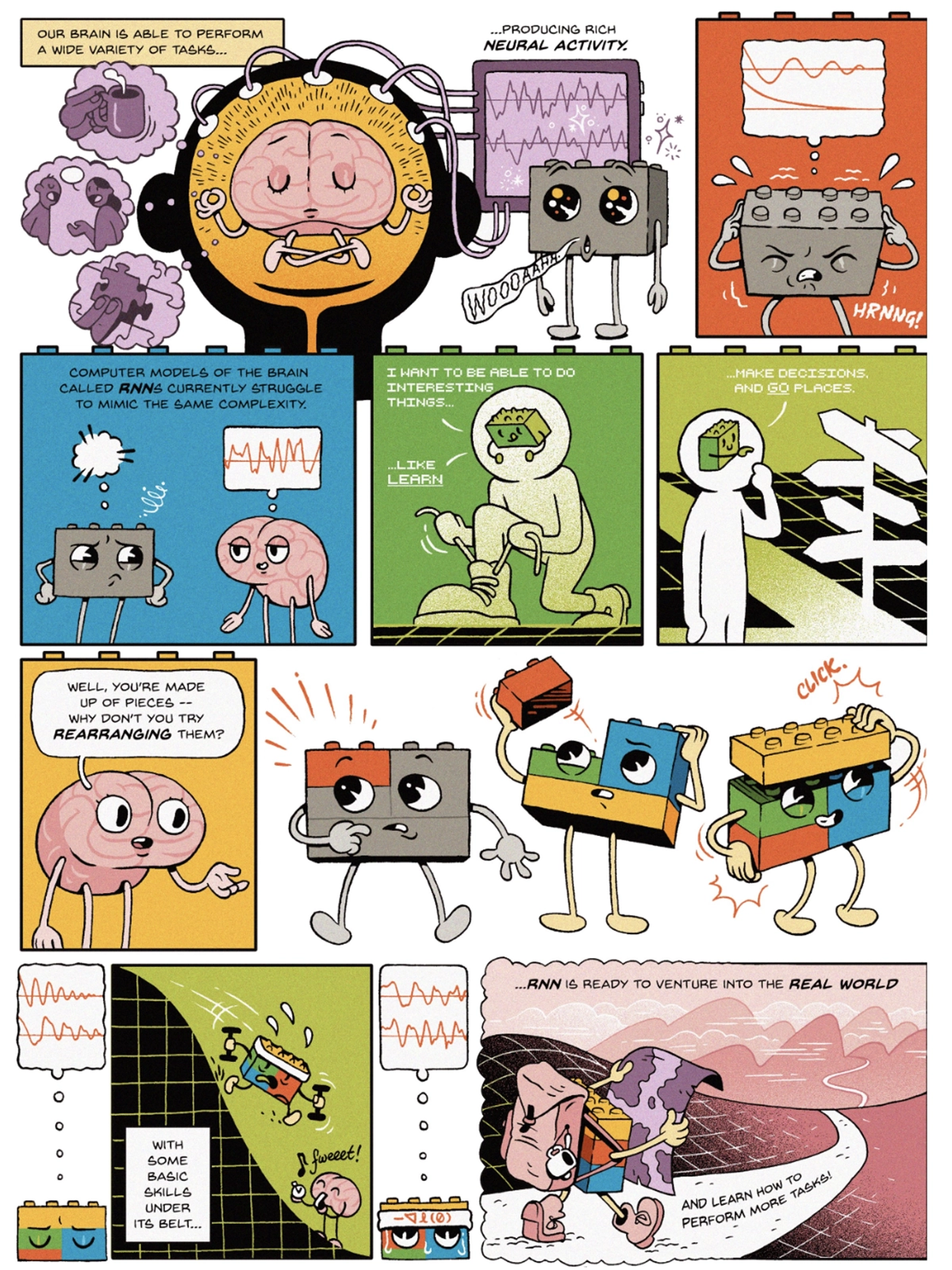

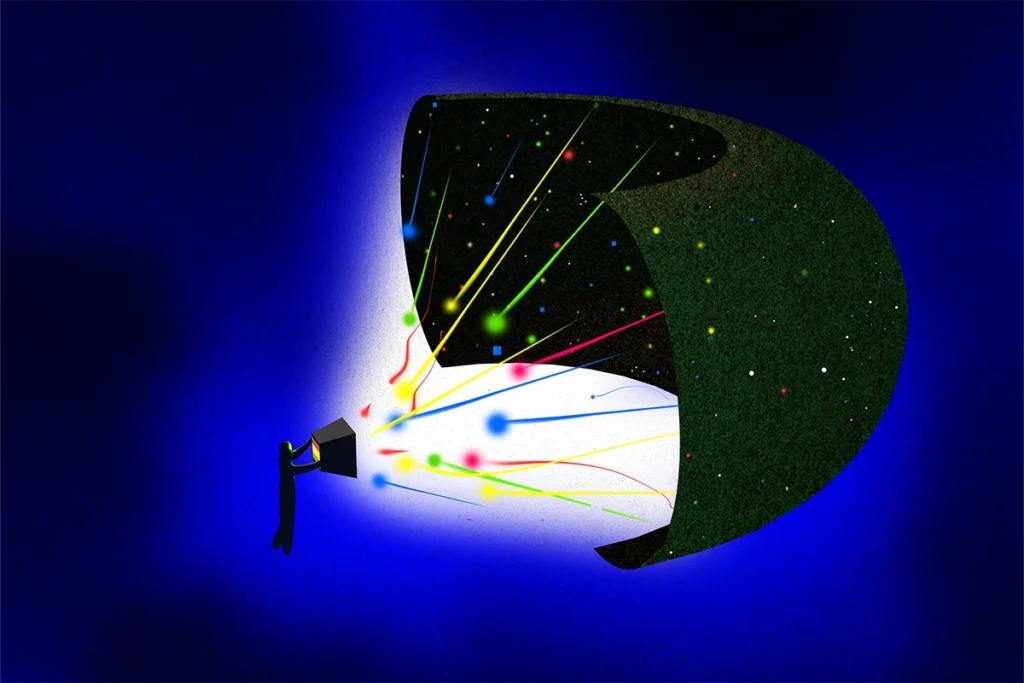

KR: One year, I was asked to lead a workshop at the Computational and Systems Neuroscience (COSYNE) meeting. I was meant to teach them foundations of why it is that neural network models are such a big deal in neuroscience. And when I was trying to explain that on my own, without a professional artist, I tried to use the metaphor of a lightbulb. I said, “When we first built models of the brain, we were building models that were like lightbulbs, but the problem with those models is that they didn’t do anything. When they tried to do something, they would blow up.”

Then, once the field started using nonlinear recurrent neural networks (RNNs), we needed a new metaphor. We had this lightbulb that blew up, and we turned it into a lava lamp, because now you have interesting dynamics within the model. But in a lava lamp, these interesting dynamics are all chaotic: Every time I turned it on, it was a different pattern.

So the thesis of my talk was that, if you add inputs to the model, you can quench the chaos somewhat—and then you can get reliable responses.

There are lots of ways in which the lightbulb analogy is imperfect, though. For one thing, it’s just this one object. And everyone knows that when the switch is off, the brain doesn’t shut down. It’s contrived at best.

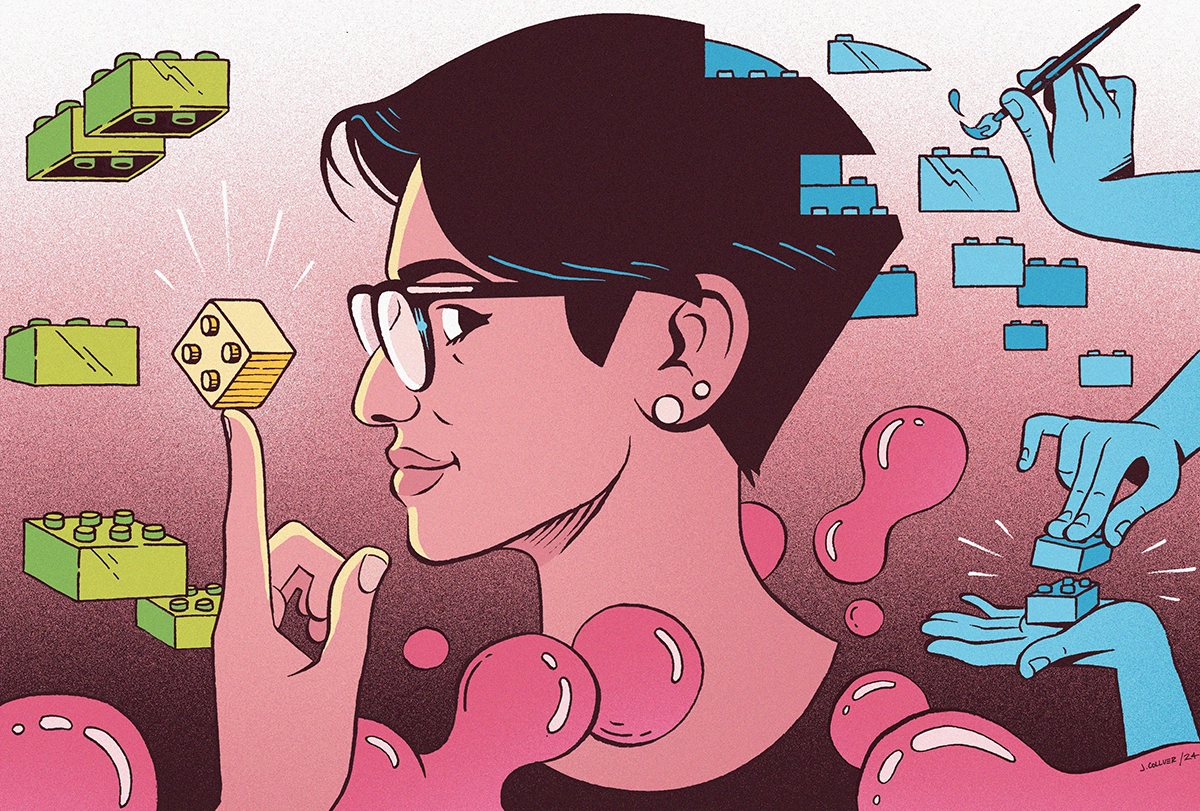

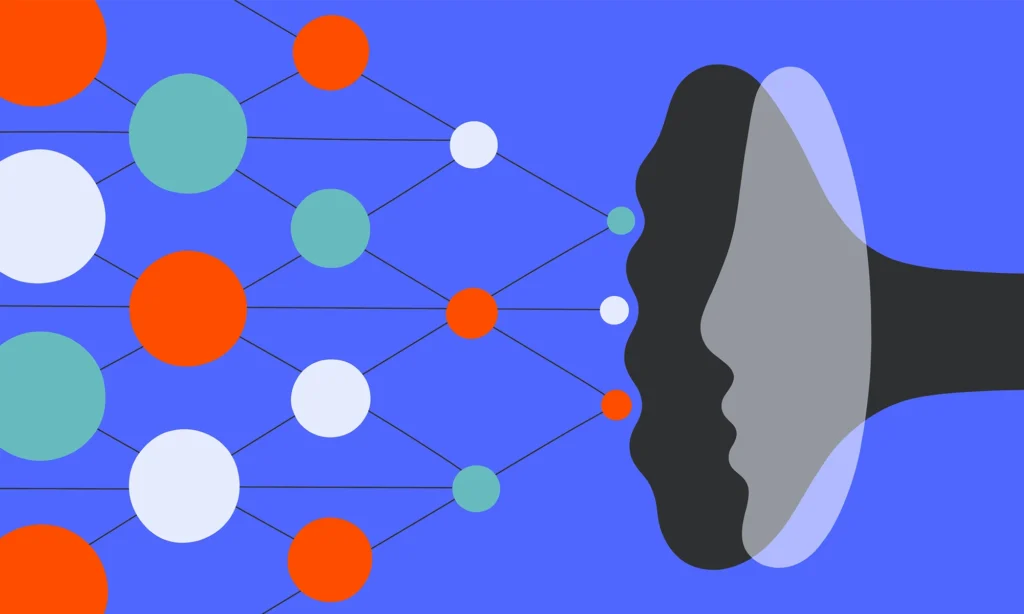

Now let me show you what happens when a professional takes over: Here comes Jordan Collver, who is an illustrator and science communicator. And he turns that story into a comic that contains the exact same content but with a completely different metaphor. He said forget the lightbulbs; get to the meat of the problem: What does it mean to train a network? He was like, “I don’t have a metaphor to connect lightbulbs with training of a model. But I do for Lego blocks.”

Everyone knows Lego blocks. They come in different colors. There are various shapes of them already. You can mix and match them. The metaphor was just so beautiful and adaptable, flexible and universal, that it basically left the lightbulb in the dust.