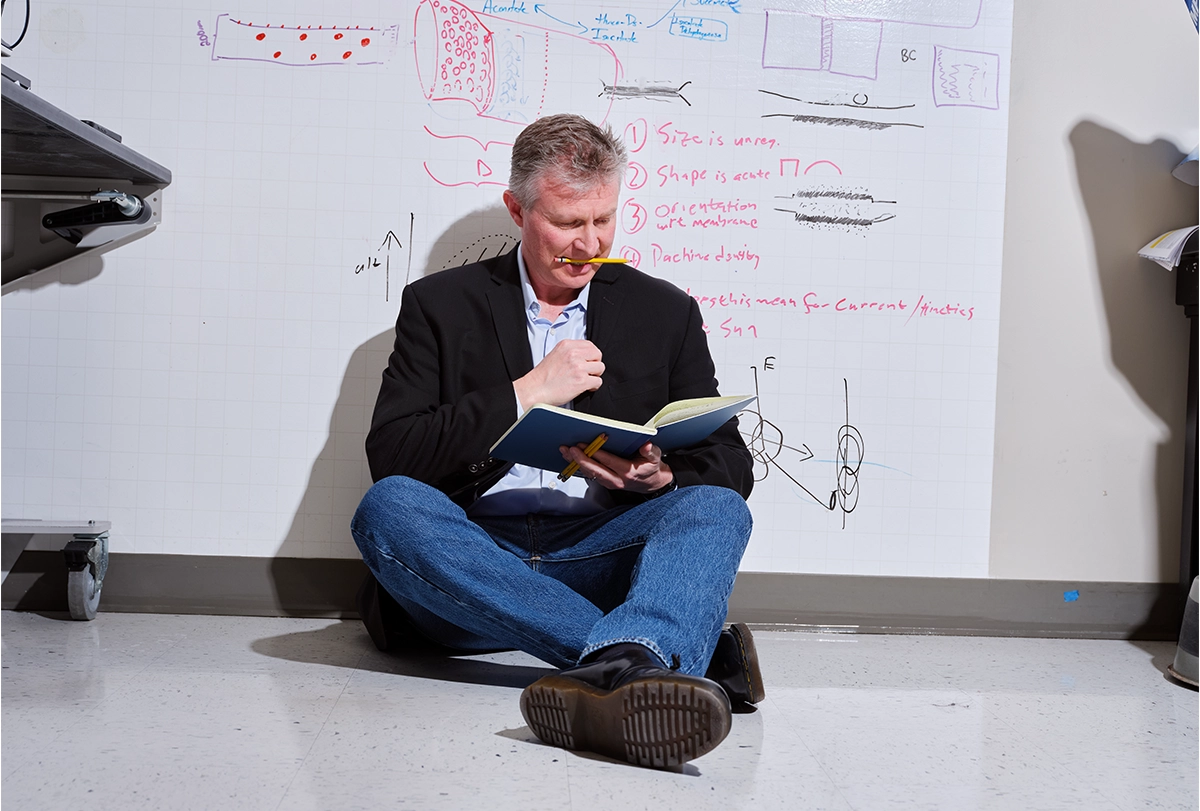

In 1989, long before he became a neuroscientist, Bryan W. Jones stopped by a thrift shop in Brooklyn and, on a whim, bought a used Leica M6 camera. The purchase changed his life.

In the next couple of years, dyslexia would derail his adolescent dream of becoming a pilot in the U.S. Marine Corps—something he says he wanted to pursue after seeing an AV-8B Harrier jet’s short takeoffs and near-vertical landings. But armed with his Leica, he developed a keen sense of photography, and he later parlayed his youthful interest in military technology into a part-time job as a photojournalist, documenting the voyages of nuclear submarines and drone operations.

At the time, he was also working as a postdoctoral researcher in neuroscience—a field he fell in love with after considering medical school and working in a sleep lab. When he and his wife began thinking about having a family, traveling to war zones for work started to seem less appealing, he says. He turned to science full time.

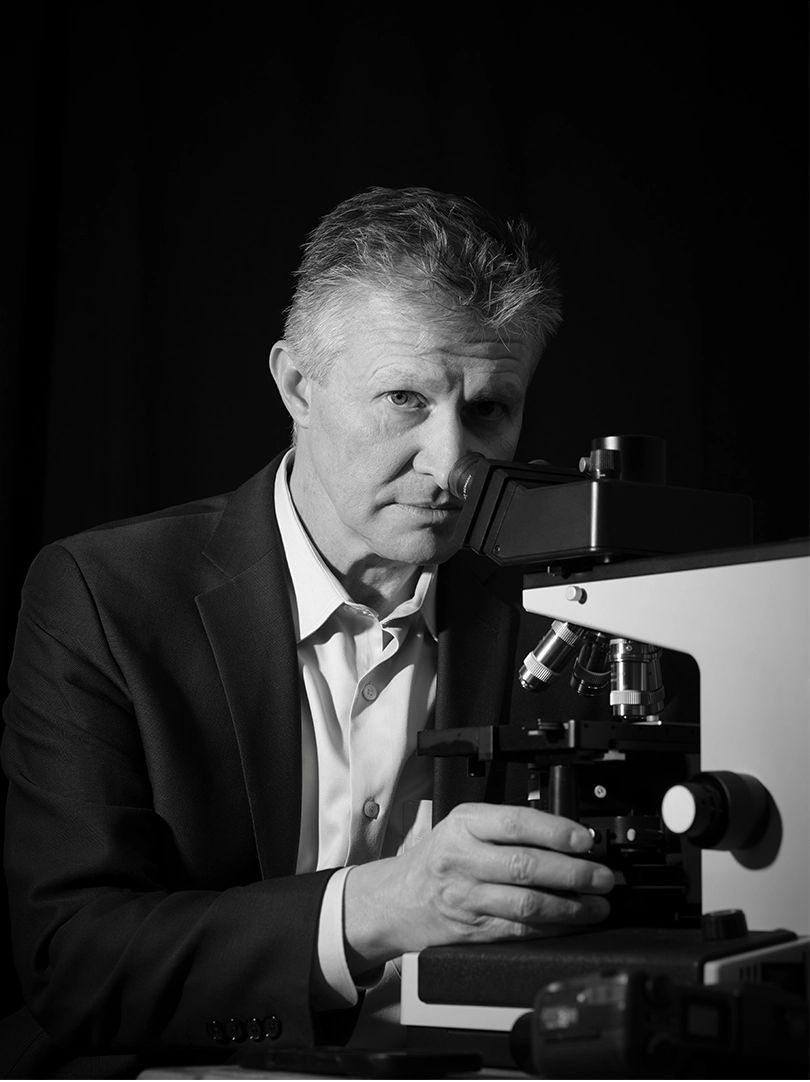

But he never gave up his love of photography. Now Jones is associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Utah, where he studies how the retina remodels itself during disease. There, too, he regularly takes portraits of other researchers—his way of documenting the people behind the science.

“At the time, it’s a snapshot. But in the context of history and time, it becomes more valuable,” he says.

Jones spoke with The Transmitter about what led him to retina research and what photography can reveal about both vision and the process of science.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: Why the retina?

Bryan W. Jones: I was initially interested in epilepsy. For my graduate work, I wanted to look at the weighting of GABAergic versus glutamatergic inputs and recurrent feedback collaterals in the hippocampus. What I had read is that you should do the dissections on cold glass plates. And it turns out that that’s great for genetic assays and routine histology, but if you’re looking at cell metabolism, as I was, you have a problem—because the small molecule export pumps work just fine at low temperatures, but the reuptake pumps don’t. As a result, depending on how long the tissue was sitting on the cold glass plates, the cells were dialyzing at different rates. So my data was all over the map, and at the time, I didn’t understand why.