This past April, more than 280 researchers (that number has since climbed to 480) issued a declaration on animal consciousness, claiming “there is strong scientific support for attributions of conscious experience to other mammals and to birds” and “at least a realistic possibility of conscious experience in all vertebrates … and many invertebrates.” This broad overstatement, in my opinion, could hurt scientific research in several ways.

The background document accompanying and supporting the declaration, called the New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, focuses on phenomenal consciousness, a term introduced by the philosopher Ned Block to describe the “pure,” qualitative aspects of subjective experiences, such as the redness of red or the painfulness of pain. Block used the term to distinguish phenomenal consciousness from other notions of consciousness, such as the capacity to behave flexibly, which includes learning and reacting meaningfully to stimuli.

By definition, these phenomenal experiences need not come with significant cognitive consequences—they may be fleeting, and an animal may not notice them. As such, they can be difficult to measure experimentally. Indeed, the empirical investigation of phenomenal consciousness is controversial, even in humans. A person may not track a series of letters on a license plate well enough to immediately recall all of them, for example. But she may be able to accurately report some of the digits if given an appropriate cue to focus on just a subset. Some researchers interpret this observation as evidence that the viewer processes the entire set of letters and is phenomenally conscious of them. Arguments of this kind remain contested, but they give an idea of the kind of painstaking work needed to establish the existence of phenomenal consciousness, or its absence.

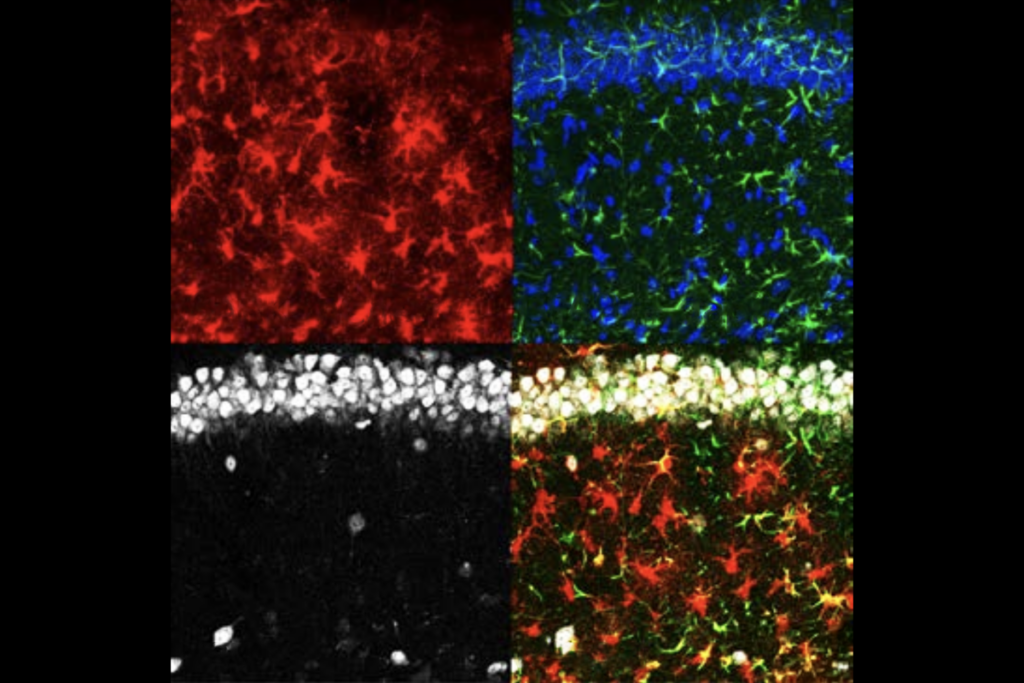

Because there are no agreed-upon neural signatures for the phenomenon, the declaration relies instead on evidence that generally concerns flexible behavior, arguing that animals’ display of learning, memory, problem-solving and self-awareness are signs of phenomenal consciousness—a clear deviation from the definition. In a personal correspondence, Jonathan Birch, one of the writers of the declaration, says that although phenomenal consciousness is conceptually distinct from forms that support flexible behaviors, the two may turn out to be empirically identical, or at least tightly related.

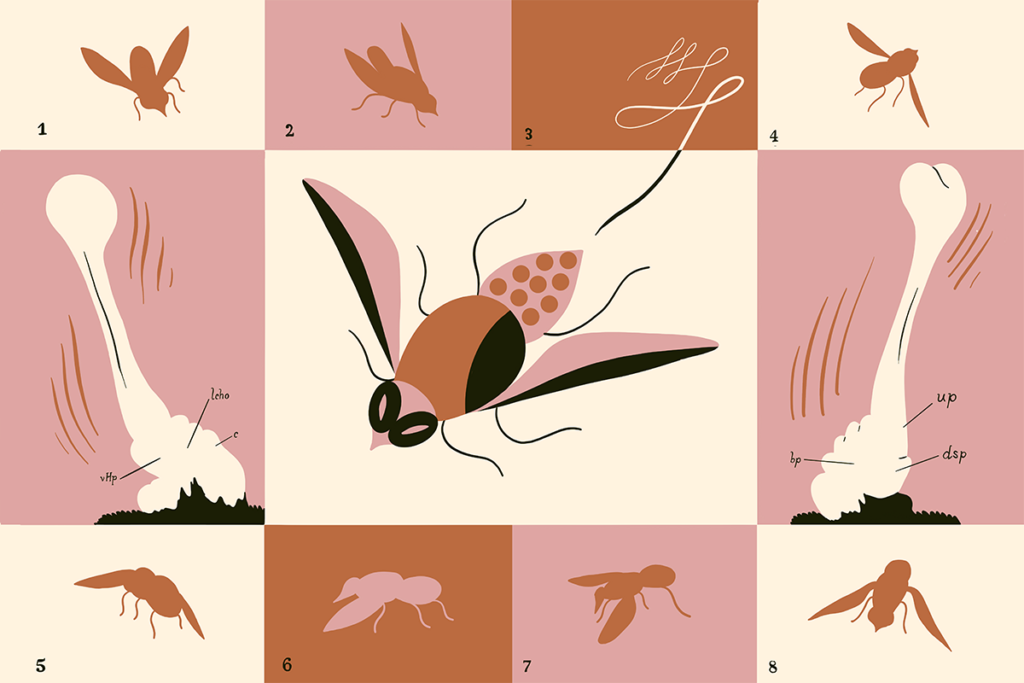

We already know, however, that they can dissociate. For example, people with blindsight report having no subjective experience in their affected visual field. But they can guess the identity of visual stimuli, spontaneously avoid obstacles and learn to react to threats presented in their “blind” fields. Relatedly, decapitated insects and even plants show some signs of learning. In other words, none of the evidence cited in support of the declaration unequivocally points to phenomenal consciousness rather than the general capacity to behave flexibly. The latter can demonstrably exist without the former.

M

y point is not to say that birds and other mammals decidedly lack subjective experiences. Like many other people, I’d like to believe that these animals are probably phenomenally conscious. Some findings are suggestive perhaps, but they are far from definitive. Making a public declaration that there is “strong evidence” of phenomenal consciousness in animals suggests we can already reliably and unequivocally measure it, which is not yet the case. And prematurely declaring a consensus stands to impede efforts to develop more accurate ways of assessing it.These kinds of broad statements can have other negative consequences as well. The message broadcast in media reports is that experts have declared insects to be conscious, which could galvanize misinformed animal-rights activism. Statements about fish sentience, for instance, have reportedly stifled research, making it more difficult to obtain funding.

As much as it’s the media’s responsibility to avoid exaggeration, it’s not entirely surprising that it happened in this case. Some of the wording in the declaration—promoted at a public event—is ambiguous. Given that there are well-known skeptics (for example, Joseph LeDoux) of animal consciousness even in rodents, it is not clear what “wide agreement” the declaration refers to. And with regard to phenomenal consciousness in birds, it’s not at all clear that “strong scientific support” actually exists.

Indeed, the science of consciousness has become a splashy area that receives a lot of media attention. Last year, one study prompted multiple news reports in major scientific and popular media outlets prior to peer review, and this widespread attention ultimately attracted substantive criticism of the work from within the scientific community.

This new declaration is drawing a similar kind of attention, through media activities rather than rigorous peer review. I am concerned that these recent events have served to “normalize” how the New York Declaration is being put forward. Years ago, when a similar Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness was made, dozens of authors signed an open letter to criticize its prematurity. Today, it seems that the zeitgeist might have changed somewhat.

Increasingly, the science of consciousness is being called to the stand to make ethically far-reaching statements on controversial topics such as abortion, organoid research and artificial-intelligence sentience. But the state of current research necessitates a level of prudence and humility from which we as a community are unfortunately straying. One likely outcome—and yet another way in which the declaration may hurt research—is that more and more serious people will stop taking the discipline seriously. Even more worryingly, this could tarnish the reputation of science as a whole.