Life as a researcher comes with a mountain of paperwork. Among the most time-consuming are the forms a scientist must submit to an institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) that detail proposed animal experiments, according to surveys on administrative burden.

A new protocol-sharing site that launched 15 January aims to lighten the load. The Compliance Unit Standard Procedures (CUSP) site enables researchers to share IACUC-approved procedures—including analgesia, surgeries, anesthesia, euthanasia, husbandry and behavioral tests, such as conditioned place preference and drug self-administration—across institutions. The project organizers plan to host a virtual “town hall” Q&A meeting about the site on 6 February.

“It avoids reinventing the wheel,” says Michelle Brot, scientific reviewer in the Office of Animal Welfare at the University of Washington and one of the CUSP project organizers. Plus, if researchers across institutions adopt the same procedures in their work, “the literature hopefully will be more consistent.”

Any institution in the United States that uses animals in federally funded research must have an IACUC that ensures these procedures comply with federal animal welfare laws; only IACUC-approved procedures can be uploaded onto the site.

Rather than scouring the literature for descriptions of methods, CUSP users can browse the secure site to find new procedures to use and borrow language to include in their own submissions.

“That could be a big time-saver,” says Joseph Thulin, emeritus professor of physiology and former assistant provost for research at the Medical College of Wisconsin, who was not involved in the project. If a procedure has already been approved, it likely “meets IACUC expectations,” he says, and so adapting it could speed up the submission and review processes. “It could be the case where you don’t have all this back and forth.”

But researchers should view the language as a template, Thulin says, and modify it as needed. And they must still submit their CUSP-derived procedures to their own IACUC for approval.

The site, which is sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Federal Demonstration Partnership (FDP), an association of federal and academic institutions that aims to make the research process more efficient, is currently open to applications from FDP member-institutions. The organizers plan to open the site up to all institutions by mid-2025. The FDP hosts the database of procedures behind a password-protected firewall; approved institutions then decide how many people from their organization will be given access to the site.

So far, users from 15 institutions have joined the site, with more registrations underway, says Aubrey Schoenleben, director of regulatory affairs and external partnerships in the Office of Animal Welfare at the University of Washington and one of the CUSP project organizers. Researchers who want to join CUSP should contact their institution’s IACUC or other administrator, Schoenleben says, and the CUSP team is available to answer any questions through an online help desk.

“For resources like CUSP, they’re only as good as they are used. So the more folks that we have in there engaging with the system, contributing to the system, the better it is for everybody,” she says.

I

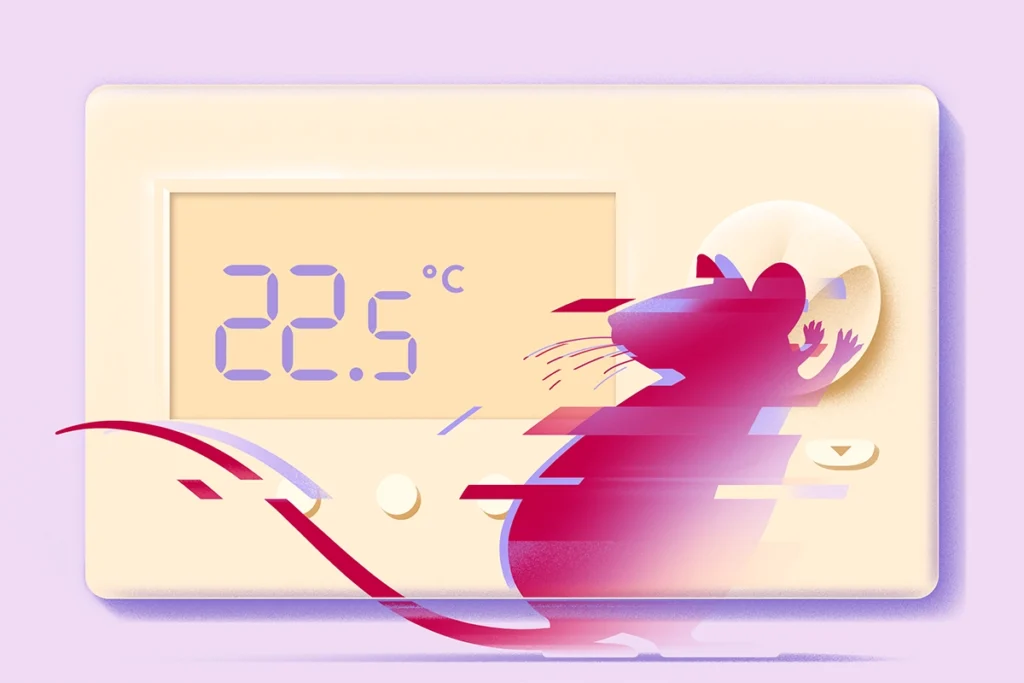

n addition to standard animal models, the CUSP site includes a section for cephalopods and other atypical lab animals—a feature that could “revolutionize” the burgeoning cephalopod neuroscience field, says Robyn Crook, associate professor of biology at San Francisco State University, who participated in discussions with the CUSP organizers about including cephalopods in the site.Neuroscientists lack a standardized way to share husbandry and welfare information about octopuses, squids and cuttlefish and instead rely on personal communication or hunt for descriptions scattered throughout the literature. CUSP represents “the first time that we have this ability to standardize procedures and share them in a platform that’s secure, which I think is a huge benefit as the community grows,” Crook says.

At the end of 2023, the U.S. government proposed regulating cephalopod research. Although researchers working with these animals are not currently required to submit their proposed experiments to an IACUC, some, including Crook, already do. In lieu of federal guidelines, “standardization across labs is the best way to arrive at best practices,” she says. Some institutions have a local library of IACUC-approved procedures but have no way to compare their pool with those at other institutions.

“Being able to go into something like CUSP and see at a glance all of the variations of a given procedure at these different institutions—it’s so much more efficient but also starts to show you where the consensus is building on things like anesthesia practices and analgesia,” Crook says. “All of these welfare-enhancing things that are quite difficult to find in the literature; they could all be right there. And that would be a huge advantage.”