Two neuro-oncologists who uncovered how neural activity can contribute to the spread and growth of cancer throughout the brain and body have been awarded this year’s Brain Prize.

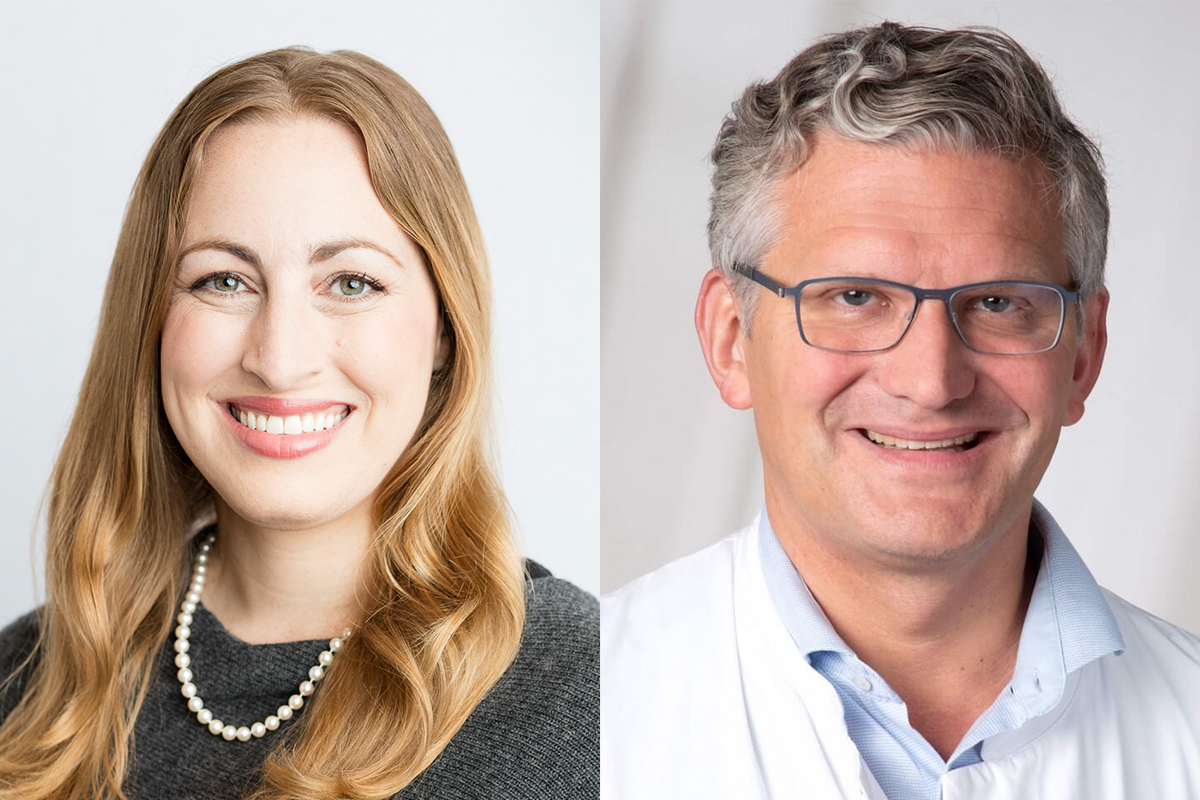

The winners—Michelle Monje, professor of pediatric neuro-oncology at Stanford Medicine, and Frank Winkler, professor of experimental neuro-oncology at Heidelberg University—were announced today in Copenhagen by the Lundbeck Foundation, which founded the award in 2011. The pair will receive 10 million Danish kroner (about $1.4 million)—the world’s largest award for neuroscience research.

Monje and Winkler, both neuroscientists and practicing neuro-oncologists, investigated the interactions between glioma cells, or brain tumor cells, and neurons. Their labs independently and simultaneously discovered that cancer cells can form synapses with neurons. Their work characterizing the molecular and cellular basis of these connections has “pioneered a paradigm shift incorporating neuroscience into cancer research,” said Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg, chair of the Brain Prize Selection Committee, in a press release.

“I’m hopeful that it will encourage other scientists to come into the field and study these important questions,” Monje told The Transmitter.

Prior to Monje and Winkler’s research, scientists knew peripheral nerves could play a role in tumor growth in other parts of the body, such as the pancreas and prostate, but those mechanisms had not been studied in the brain, says Benjamin Deneen, professor of cancer neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine. “Them winning this prize speaks to sort of embracing this idea that the principles of neuroscience are fundamentally important—not just for brain cancer, but for all cancers.”

W

hen neuronal activity increases, brain tumors grow more rapidly, Monje and her team discovered in 2015. Active neurons secrete a protein called NLGN3, which spurs much of that development—and inhibiting its release from neurons stymies tumor growth, the team found. What’s more, neurons form glutamatergic synapses with gliomas, through which cancer cells siphon off resources and hijack the standard neuronal mechanisms of development and plasticity to grow and spread, Monje’s team showed in 2019.Meanwhile, Winkler and his colleagues discovered in 2015 that gliomas grow long, neurite-like extensions called “microtubes” that enable the cells to communicate and connect over long distances. Microtubes contribute to glioma’s resistance to surgery and standard chemotherapy, but inhibiting the connections can thwart tumor growth. He and his team then independently found that synapses exist between neurons and gliomas and published their discovery alongside Monje’s in Nature in 2019.

When two labs independently uncover similar results, it’s much more credible, Winkler says.

“This is a wonderful example of science as it should be: that we’re all seeking what is true and useful, and it’s not about competition,” Monje adds.

Both Monje and Winkler say they are working to translate their work into new cancer treatments, including through multiple clinical trials.

Winning the Brain Prize speaks to the “vitality” of the field of cancer neuroscience and the opportunity to develop a better understanding of how cancer works and improve cancer therapies, Winkler says. “I think it’s a prize for the entire field.”