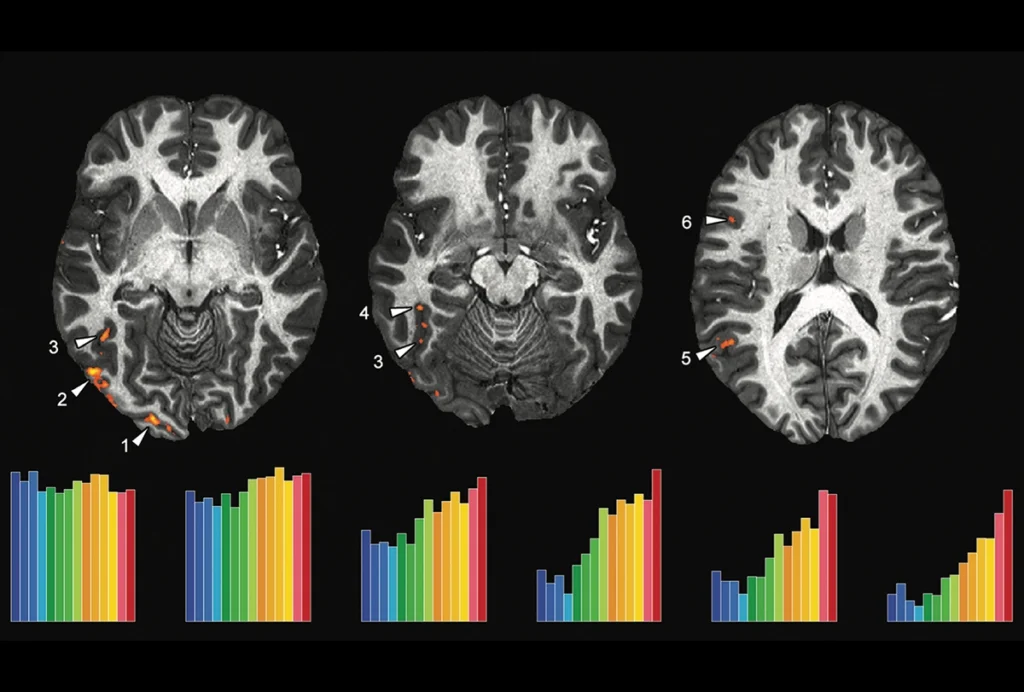

A decade ago, Nick Turk-Browne unintentionally created a paradox. He demonstrated in a series of studies that statistical learning, or the ability to extract patterns from experiences, depends on the hippocampus, a brain region also involved in forming episodic memories. And yet he knew from past work that babies, who were thought to not form such memories, are excellent statistical learners—it’s one of the main ways they acquire language.

“The lore in the memory literature was that the hippocampus doesn’t really come online until age 4 or 5,” says Turk-Browne, professor of psychology and director of the Wu Tsai Institute at Yale University. So how, he wondered, could infants be such good statistical learners?

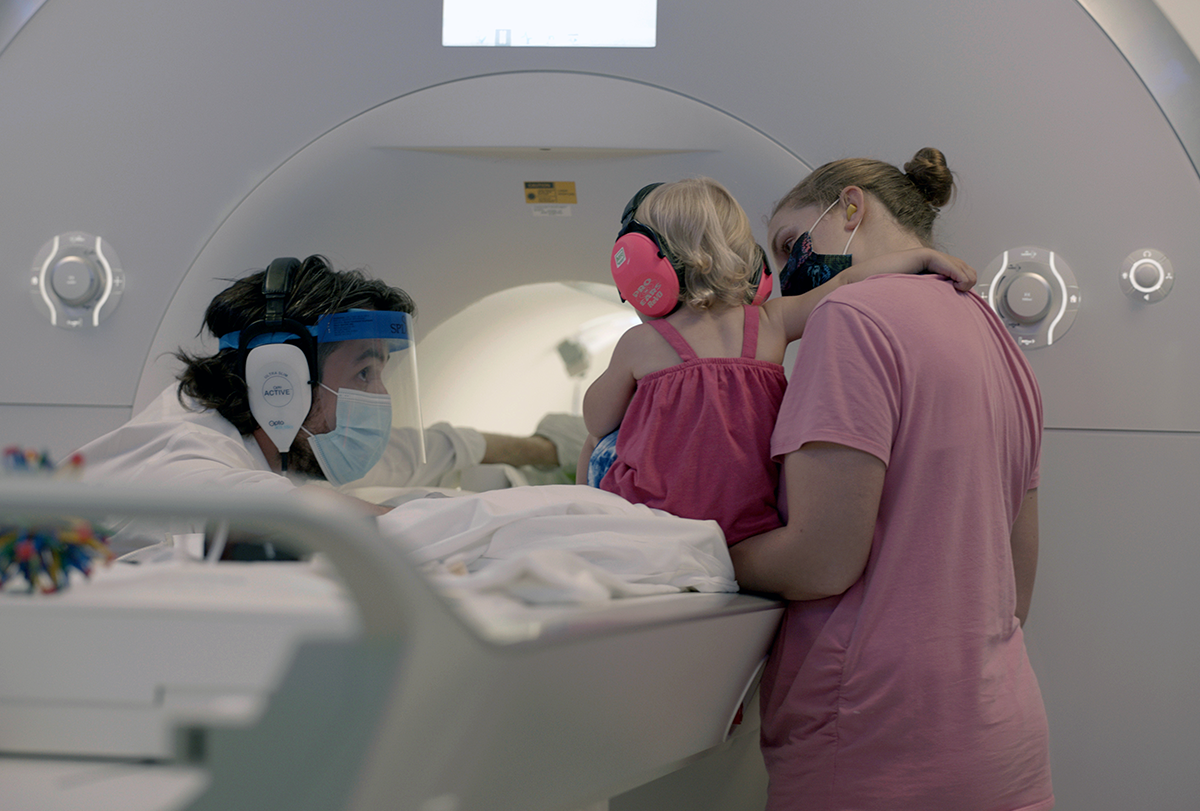

The only way to settle this conundrum, Turk-Browne reasoned, would be to measure activity in the hippocampus of awake infants, like he did for his statistical-learning studies in adults. But babies are terrible functional MRI (fMRI) participants: They wiggle, cry, fall asleep and cannot take instructions, which is why they are typically scanned while sleeping or sedated. On the other hand, the neuroimaging methods used in awake infants can’t record activity from the hippocampus and other deep brain regions.

Turk-Browne and his team “somewhat naively” endeavored to make fMRI a suitable method for awake infants, he says. “We had to try it, because it’s the only way of measuring brain activity in some of these really critical systems.”

It took a lot of troubleshooting, but the effort eventually produced data that untangled the contradiction: The hippocampus activates during statistical learning as early as 3 months of age, the team reported in 2021. By age 1, it is also active during memory encoding, meaning our lack of infant memories is likely due to a memory retrieval issue, according to findings Turk-Browne’s lab published today in Science.

Turk-Browne is part of a small but growing number of cognitive neuroscientists who have taken on the challenge of scanning awake infants. “It’s become a field in kind of an amazing way,” says Rebecca Saxe, professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After a decade of technical fits and starts, the method is poised to answer questions about how and when the infant mind takes shape—questions that, until now, the field has been unable to tackle.

M

uch of what we know about the infant mind is based on where babies look and for how long. Behavioral tasks often measure “looking time” to infer what an infant pays attention to and remembers. “Very detailed cognitive models have been generated based purely on behavioral data,” says Richard Aslin, senior scientist at Haskins Laboratories at Yale University, who studies language development using primarily electroencephalography and functional near-infrared spectroscopy.But looking time is an opaque measure, Aslin says. For example, in some situations an infant may prefer to look at a novel object, but in others they may gaze at a familiar object for a longer time. “Behavior alone is not sufficient,” Aslin says. “If you want to pinpoint the underlying mechanism, you pretty much have to study the brain.”

The first fMRI scans of sleeping or sedated infants took place in the late 1990s. They measured resting-state activity and revealed “how competent the developing brain already is,” says Petra Susan Hüppi, professor of pediatrics at Geneva University, who was an early adopter of fMRI in infants. Resting-state work continues today, through collaborative efforts such as the Baby Connectome Project and the HEALthy Brain and Child Development Study.

Combining infant neuroimaging with behavioral data and adult cognitive neuroscience studies can help “triangulate the answer to questions about the developing brain and mind,” says Michael C. Frank, professor of human biology and psychology at Stanford University. “Putting those different sorts of information together, ideally with computational theories as the glue, then provides our best guess as to what’s going on.”

But scans in sleeping babies cannot unpack the neural mechanisms driving “high-level cognitive function,” says Ghislaine Dehaene-Lambertz, scientific director of the developmental neuroimaging lab at Neurospin. For that, the babies need to be awake.

The first attempts to scan awake infants were riddled with technical hurdles—and not-so-technical ones. In one early experiment, Dehaene-Lambertz played normal and reversed clips of speech to 2- and 3-month-old infants while they lay in the scanner. “The first baby was perfect,” she says, and her team captured a “beautiful” blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal, a proxy for brain activity. But the subsequent 19 participants were a mixed bag: All but six babies fussed or fell asleep. In those six, though, a portion of the frontal cortex had a stronger BOLD signal in response to normal speech than reversed speech, the team reported in a 2002 paper.

Saxe picked up the baton when she opened her lab in 2006, but scanning infants proved more difficult than she expected. “The first paper in my lab on that came out in 2017,” she says. “That is maybe an honest signal of how hard it was to get this to happen, for all kinds of reasons.”

In addition to trying to keep the babies awake and engaged, Saxe says she worried about how to protect her tiny participants’ hearing and minimize their head motion. In adult studies, participants wear earplugs and covers and, unlike babies, can alert researchers if their hearing protection slips out. Adults can also wear a head coil that gently presses on their skull to reduce motion, but infants, who have soft skulls, cannot.