Michael Ehlers

Neuroscience Chief Scientific Officer

Pfizer

From this contributor

A cautionary tale for autism drug development

Poorly designed animal drug studies for motor disorders have led to spurious conclusions for the clinical trials that follow. This may be even more true for autism research, says Michael Ehlers.

SHANK mutations converge at neuronal junctions in autism

SHANK3, one of the strongest candidate genes for autism, has the potential to be a molecular entry point into understanding the synaptic, developmental and circuit origins of the disorder.

SHANK mutations converge at neuronal junctions in autism

Drug zone

Rodent and stem cell models remain challenging for developing psychiatric drugs, says Michael Ehlers, chief scientific officer of neuroscience at Pfizer.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects

The "intuitive" neuropharmacologist pushed against the status quo.

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects

The "intuitive" neuropharmacologist pushed against the status quo.

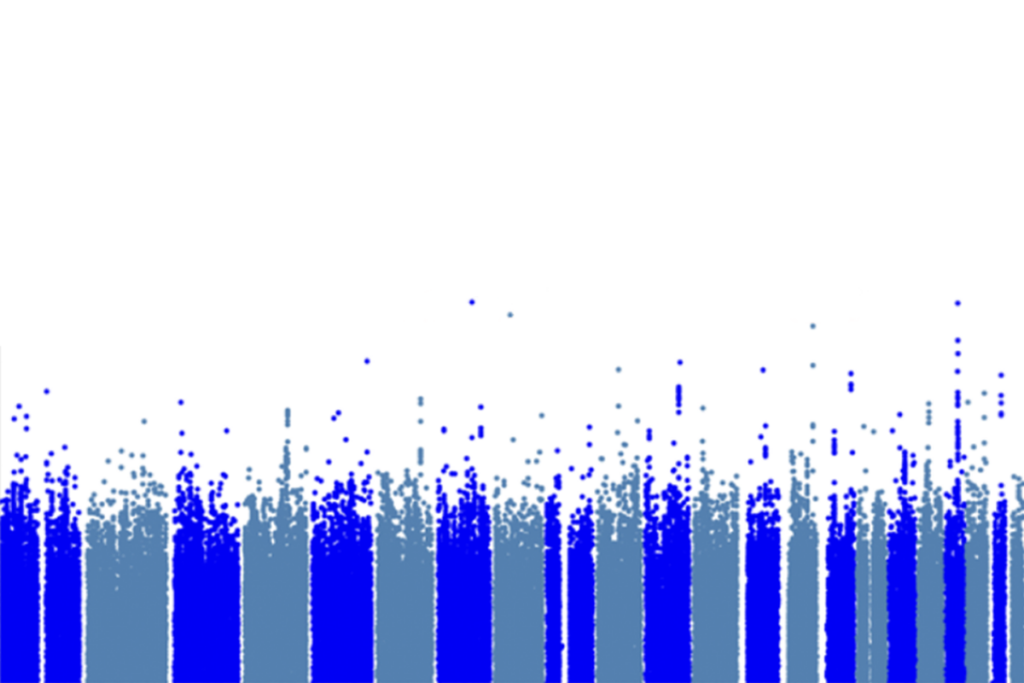

Revised statistical bar extracts less-common variants from autism genetics studies

Adjusting genetic analyses could help plug autism’s heritability gap, according to a new preprint.

Revised statistical bar extracts less-common variants from autism genetics studies

Adjusting genetic analyses could help plug autism’s heritability gap, according to a new preprint.

Tom Griffiths describes how neural networks, logic and probability theory together explain cognition

In his new book, “The Laws of Thought,” Griffiths shows how these three pillars of study complement one another and together form a solid foundation to eventually explain all of our cognition, from brain to mind.

Tom Griffiths describes how neural networks, logic and probability theory together explain cognition

In his new book, “The Laws of Thought,” Griffiths shows how these three pillars of study complement one another and together form a solid foundation to eventually explain all of our cognition, from brain to mind.