Neuroscience research relies overwhelmingly on a single model system—the mouse—to address human health challenges. Yet mice rarely replicate the complexity of human diseases, particularly in the brain, and treatments that show promise in mice often fail to translate effectively to people. Studying endangered animals in zoos could be a powerful approach to simultaneously improve animal welfare and advance human brain health.

Laboratory experiments done in mice are valuable; they provide a highly controlled environment to uncover causal relationships between variables. But mice don’t often spontaneously develop a disease of interest, and genetically engineered mice in isolated labs fail to capture the environmental factors that can play a critical role in the development and manifestation of complex human diseases. We have invested heavily in the genetics of mouse models to study mental health, but those studies have revealed that gene variants often have a small impact on the etiology of many human mental health conditions.

Harnessing biodiversity offers a new route to understand the complex interplay between genetics and environment in mental and other health issues and could simultaneously help improve the well-being of endangered animals.

Humans and zoo animals, for example, share several health concerns. Many endangered zoo animals are sedentary, overweight and live relatively long lives. Some suffer from depression and anxiety—you might have seen a polar bear, panda or lion pacing back and forth in their enclosure at the zoo, an indicator of anxiety known as stereotypy. Indeed, many zoo animals are treated with the same antidepressants commonly used to reduce depression and anxiety in humans.

Studying how enclosure size, social interactions and exercise influence mental health in endangered species offers a new way to explore how specific environmental factors affect the brain, and it could identify concrete ways to improve conditions for zoo animals. For species with thousands of animals in captivity, such as tigers, we could harness big data to identify the interactions between genetic and environmental factors, such as stress and exercise, that underpin depressive or anxiety-like behaviors across multiple species.

Z

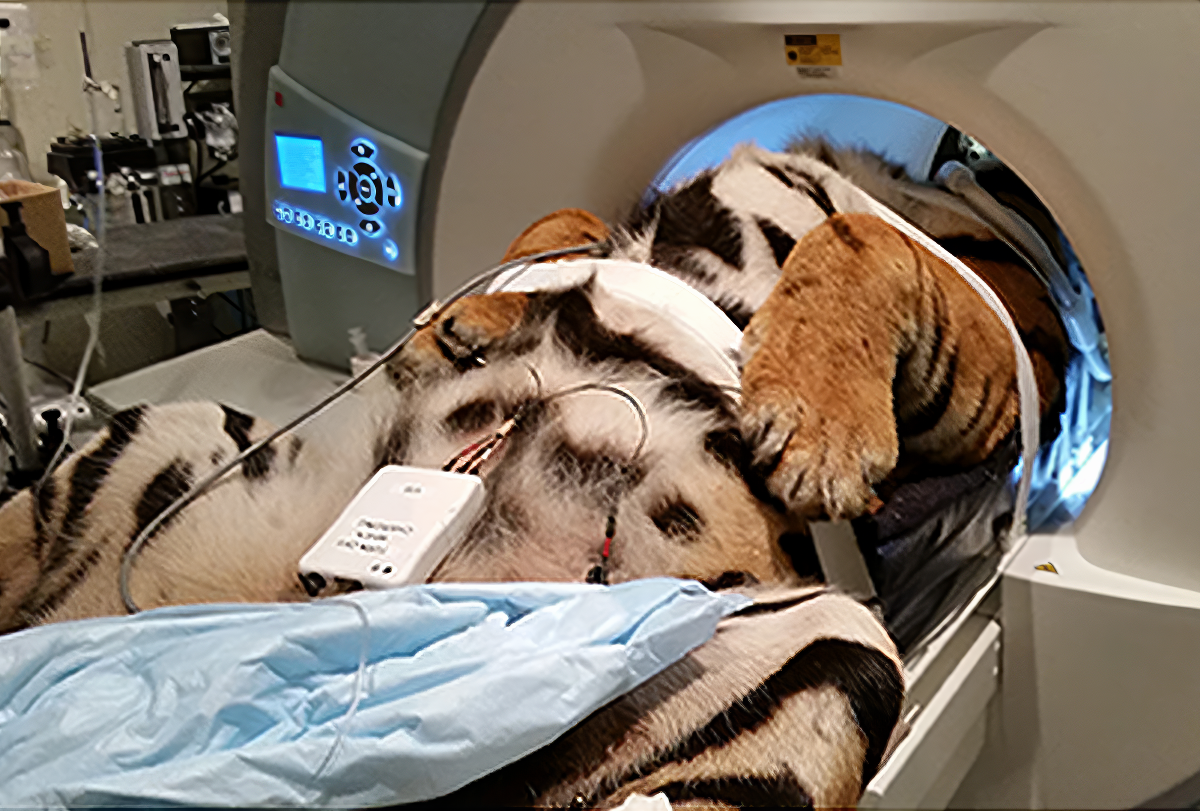

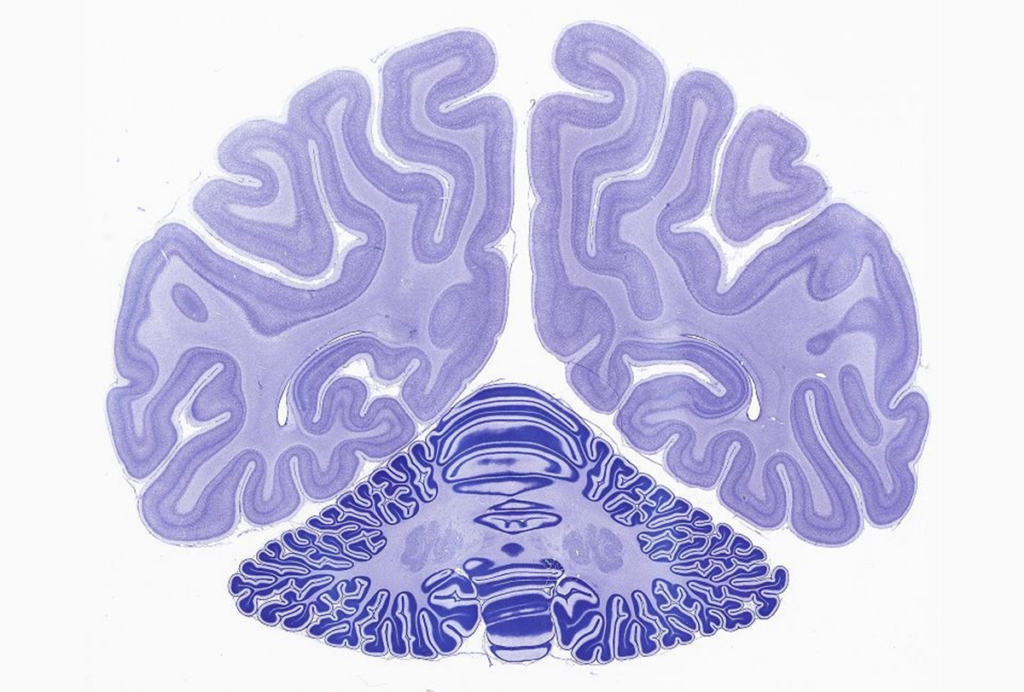

oo animals also offer the opportunity to study brain health over the lifespan. As part of their medical care, some animals undergo MRIs for neurological checkups and diagnosis. And preliminary evidence suggests that aged zoo animals may experience brain structure and cognitive changes similar to those that occur with human aging; some veterinarians report cognitive impairment in old tigers (though there is no agreed-upon test to assess cognitive dysfunction in these animals), with one study reporting evidence of brain atrophy in an 18-year-old tiger. Some species may even spontaneously recapitulate age-related diseases, making them valuable model systems.The same is true for household pets, such as cats and dogs. Because they are relatively long-lived and often receive regular veterinary care, they provide a particularly good opportunity to study age-related diseases. Like humans, some cats and dogs show signs of cognitive decline later in later life. And unlike mice, cats and dogs spontaneously develop brain plaques and tangles, the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Because these animals naturally display age-related decline, treatments that prove effective in cats and dogs are more likely to translate to humans.

Ultimately, a single species is unlikely to provide definitive answers for complex human diseases.

Combining insights from multiple systems and from different environments will be the best route to enhancing human and animal brain health—each species provides different and complementary insights into biomedical challenges. Successfully leveraging this information requires new tools for integrating information across species. Many model systems, including mice, cats and tigers, develop and age faster than humans. My team is expanding on a resource called Translating Time, which enables the alignment of ages across a variety of species. This tool helps scientists study how biological dysfunctions in model systems map onto humans and how information from humans can be used to support animal health.

Despite the promise of these approaches, funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health—as least as it currently stands—remains heavily focused on mouse models of disease. To truly understand how genetic predisposition and environmental influences interact to produce complex diseases, we need to study different species living in complex environments. Zoo and companion animals offer a ready setting to do this, but collecting large amounts of genetic and phenotypic information will require substantial investment and buy-in from the research community. Once we have these data in hand, machine-learning models can help process it and sort out which genes and environmental factors are important for healthy aging and disease progression. The outcomes will benefit both humans and animals—by identifying environmental factors that contribute to brain health and new avenues for treatment that are applicable to different species.