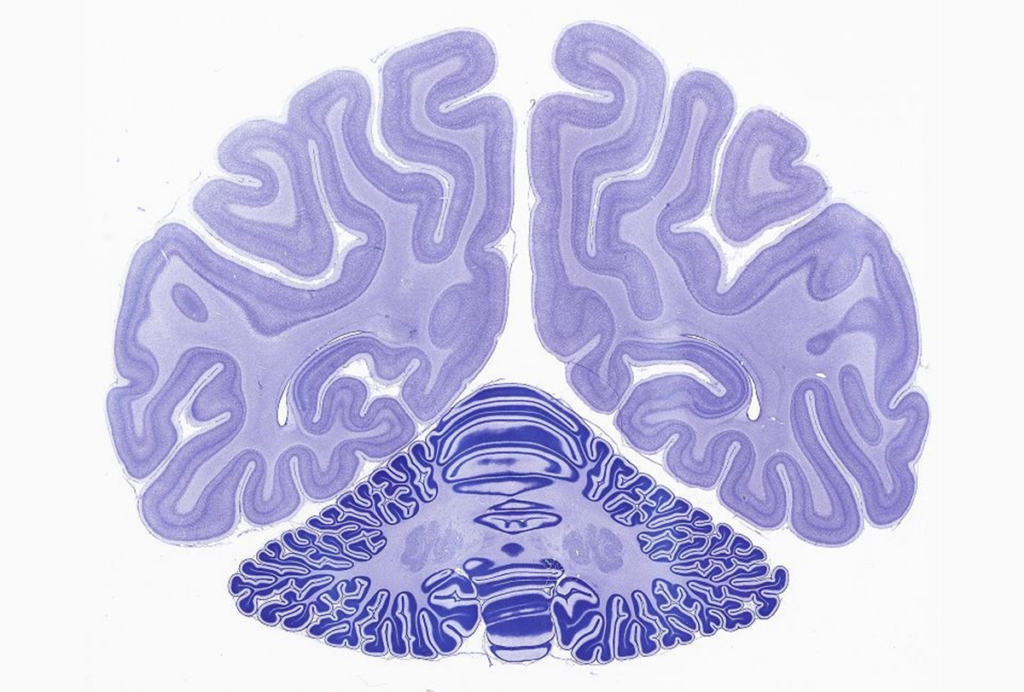

When it comes to studying how nervous systems give rise to complex behaviors, bigger animals are not necessarily better. Neuroscientists typically face a trade-off: The more cognitively sophisticated an organism is, the harder it is to comprehensively monitor and manipulate its neurons.

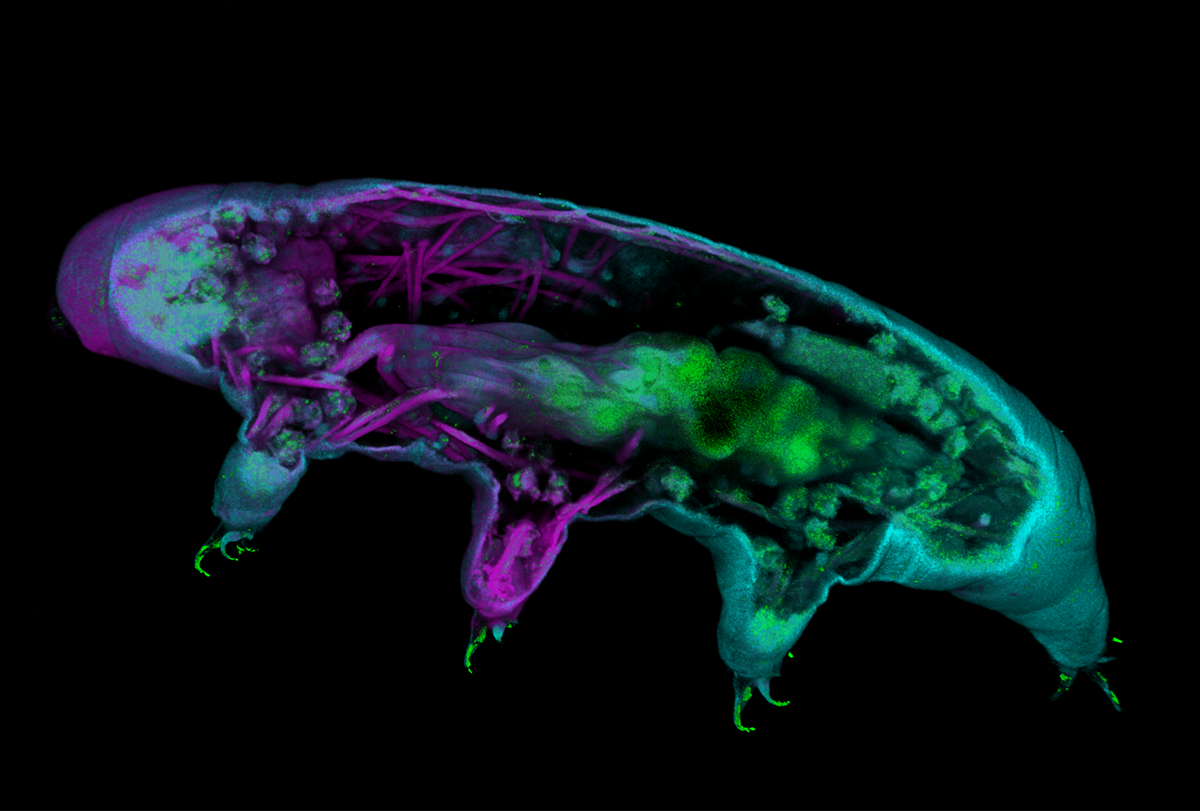

But tardigrades—millimeter-long invertebrates with a simple nervous system—offer the best of both worlds to systems neuroscientists, a new preprint argues. “Leveraging their evolutionary ties to Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, we can adapt existing toolkits to accelerate tardigrade research—providing a bridge between simpler invertebrate systems and more complex neural architectures,” its authors write.

Despite working with only a few hundred neurons, the transparent creatures have two functional eyespots and perform a range of interesting behaviors, such as mate-searching and interleg coordination across eight limbs. “Tardigrades really represent this ideal combination of traits,” says study investigator Ana Lyons, a postdoctoral scholar in Saul Kato’s lab at the University of California, San Francisco, who worked on the preprint as a Grass Foundation fellow at the Marine Biological Laboratory.

Tardigrades, which were discovered in the 18th century, exist on every continent and can survive extreme conditions, such as salty ocean water, high amounts of radiation and freezing temperatures—as low as minus 196 degrees Celsius for one species. Most research has focused on characterizing their morphology, ecology and survival ability, as well as describing the more than 1,400 known species.

But the field of neuroscience left tardigrades in the dust after Nobelist Sydney Brenner pioneered C. elegans as a model species for neural development, starting in the mid-1970s. The roundworm’s large number of offspring and short life cycle made it particularly suitable for the genetic studies Brenner and his colleagues conducted—traits that contribute to its lasting success as a neuroscience model today.

“I do wonder where neuroscience would be if they’d chosen tardigrades instead,” says Cris Niell, professor of biology and neuroscience at the University of Oregon, who was not involved in the new work.

A

fter years of working with C. elegans, Kato pivoted to studying tardigrades, inspired in part by their limbed movement, he says. Because of their round bodies and eight legs, “they look like multi-legged mammals,” says Kato, principal investigator on the study and associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. And they afforded him opportunity to “take everything that we built in C. elegans, all this great technology to interrogate the nervous system of this animal, and port it over to a slightly more complex animal.”The tardigrade’s two eyespots are particularly interesting for visual neuroscience, because most closely related organisms only have one, if any, Niell says. “They could be comparing light between eyes,” which may enable them to visually detect predators and prey, he says. “Figuring out how these little systems work and then seeing how that extrapolates up to a larger number of neurons is a really interesting question.”

Tardigrades respond to a wide range of other stimuli, such as chemicals, social interactions, temperature changes and osmotic stress. How they coordinate such responses via such a small nervous system remains an open question.

The animal’s four pairs of legs, each pair powered by a different ganglion, enable coordinated gait patterns. Tardigrades can move individual limbs when necessary, so “there’s likely to be a cluster of neurons for every limb at the end of the limb,” Kato says. They also display individual ganglia for each eyespot. This anatomical modularity “suggests that there may be a functional modularity,” Kato adds.

In comparison, the nervous system of C. elegans resembles a “big ball of string” and lacks modules linked to particular sensory or motor systems, Kato says. Studying the anatomical and potentially functional modularity in the tardigrade could reveal how local control is integrated with the top-down control by the central brain, he adds.

B

ut for all the advantages tardigrades seem to offer, their wider adoption as a model organism also presents challenges, Lyons and Kato concede.Although the tardigrade nervous system contains only a small number of neurons, for instance, each neuron might perform multiple tasks, a phenomenon called multiplexing, says Maarten Zwart, reader in psychology and neuroscience at the University of St. Andrews, who was not involved with the work. “If you have fewer neurons, you can have the same cell types do different things, which might be more difficult to understand,” compared with the motor system of, say, fruit fly larva, in which each neuron does only one task, he says. And insect motor systems show the same modularity as tardigrades, Zwart says.