Uruguayan neuroscientist Juan Ignacio (Nacho) Sanguinetti-Scheck can trace his passion for studying animal behavior in the wild to a joke he made in 2015.

He was a Ph.D. student at the time and also performed improv a few times per week. And so when he attended the Transylvanian Experimental Neuroscience Summer School that year and learned how to use virtual-reality scenarios and mazes to study animal behavior, he teased that he instead wanted to study animals in what he called “real reality.”

That crack led to a stroke of inspiration, and he came up with techniques to study the neural basis for navigation in mice living in a garden patch. “This was something that really ignited me” and fueled the work for his Ph.D. and postdoctoral research, he says.

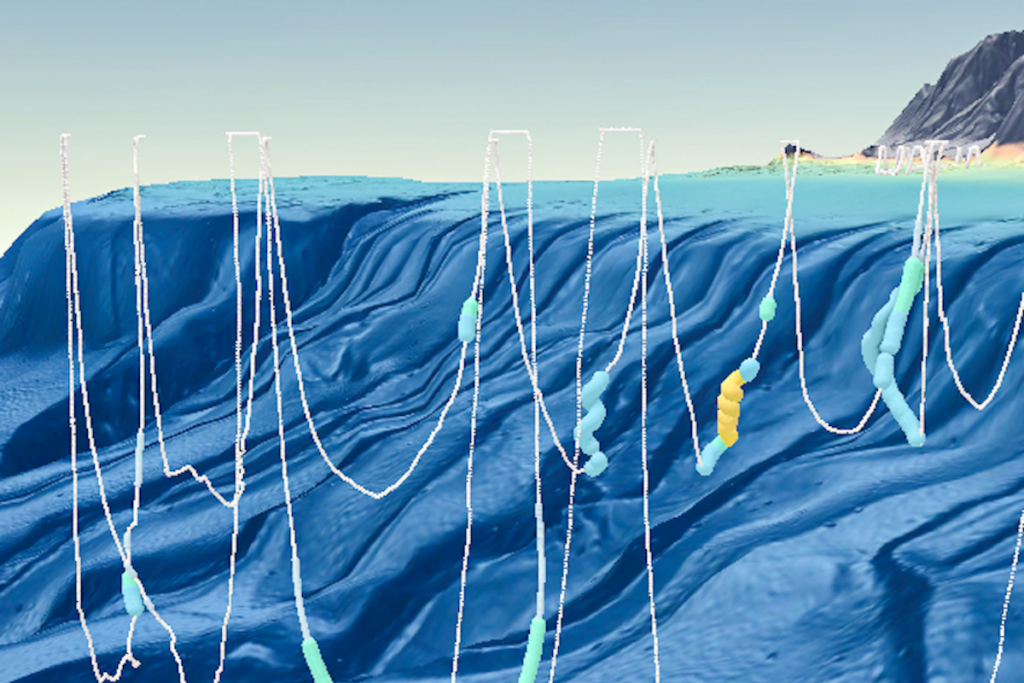

Next January, he is starting his own lab at the University of Pennsylvania, where he plans to continue to use wireless neural recordings and movement trackers on agoutis and other animals to study them living in their natural environments in South America.

The Transmitter spoke with Sanguinetti-Scheck about the parallels he sees between his background in improv and his interest in studying animal behavior in the wild, as well as his goals for his new lab.

The Transmitter: What will you focus on in your new lab?

Nacho Sanguinetti-Scheck: My new lab is going to focus on what I think of as integrative neurobiology. I want to study neuroscience and the brain from a perspective that makes sense in biology. Generally, as neuroscientists, we’re dealing with an experiment that happens in the conditions that we set and in the moment we set it to happen. But there are very deep roots of processes that are changing the experiment and the result. That’s the effect of the environment. It’s not the same to do an experiment in a tiny square box as it is to do it outside. It’s not the same to do an experiment with an orphan mouse versus a mouse that has been reared by its parents.

All these levels of processes—evolution, early life experience and environment—are influencing the experiments we do. My lab wants to have an integrative approach to neurobiology, using nontraditional model organisms and studying them in comparative ways in their natural environments, and paying attention to evolution.

TT: What are the questions or problems you most want to solve with your work?

NSS: The question driving me the most has been trying to understand how animals are capable of flexible behaviors and behaviors that we don’t understand. In any kind of science, we focus on things that are repeatable so that we can have statistical understanding of the processes. This tends to have a bias towards either things that animals do all the time that are fixed action patterns, or things that animals can be trained to do. But what I’m interested in are situations in which animals can innovate.

The way I see it is that we’re on the verge of a very interesting transition in our understanding of behavior. YouTube is one of my biggest sources of inspiration, and if you search for animal behavior you will find incredible things. You will find a dog that tries to do a cartwheel after its owner did a cartwheel. You will find a bull and a goat trying to push each other, and the bull lets itself be pushed by the tiny goat. There are all these interesting behaviors that society has observed but that scientists have not yet tackled.