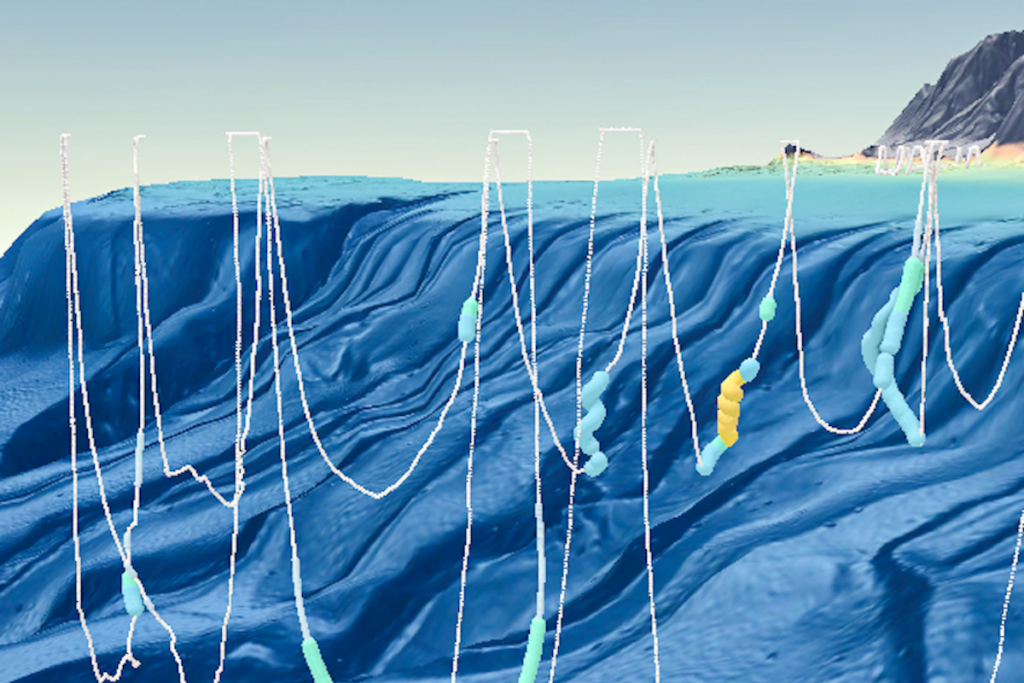

About 10 years ago, when Michael Yartsev set up the NeuroBat Lab, he built a new windowless cave of sorts: a fully automated bat flight room. Equipped with cameras and other recording devices, the remote-controlled space has enabled his team to study the neuronal basis of navigation, acoustic and social behavior in Egyptian fruit bats without having any direct interaction with the animals.

“In our lab, there’s never a human involved in the experiments,” says Yartsev, associate professor of bioengineering at the University of California, Berkeley.

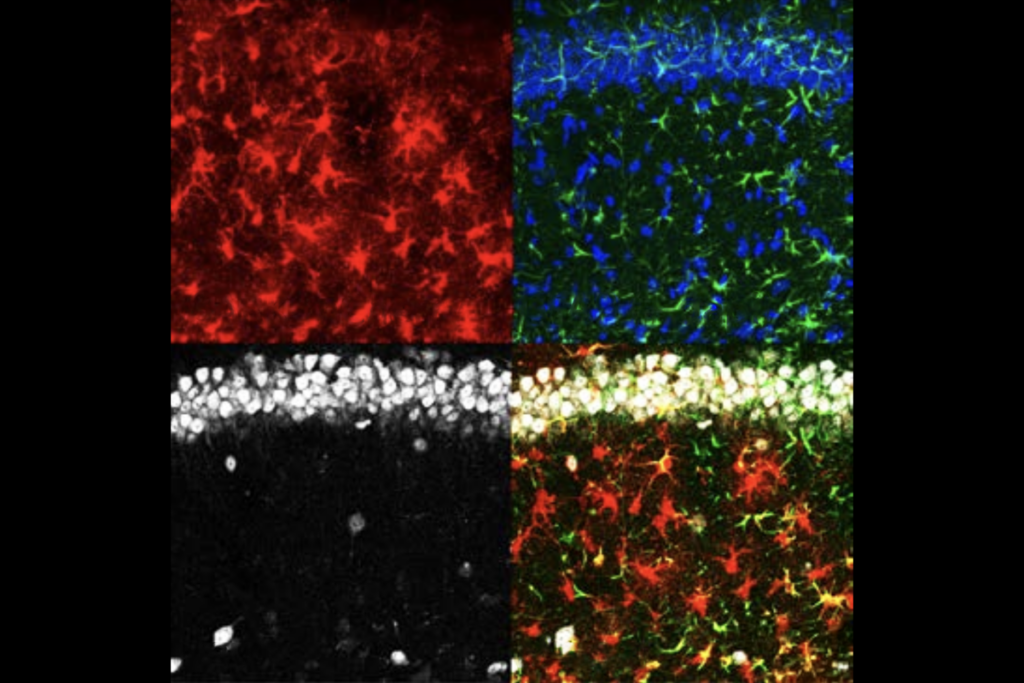

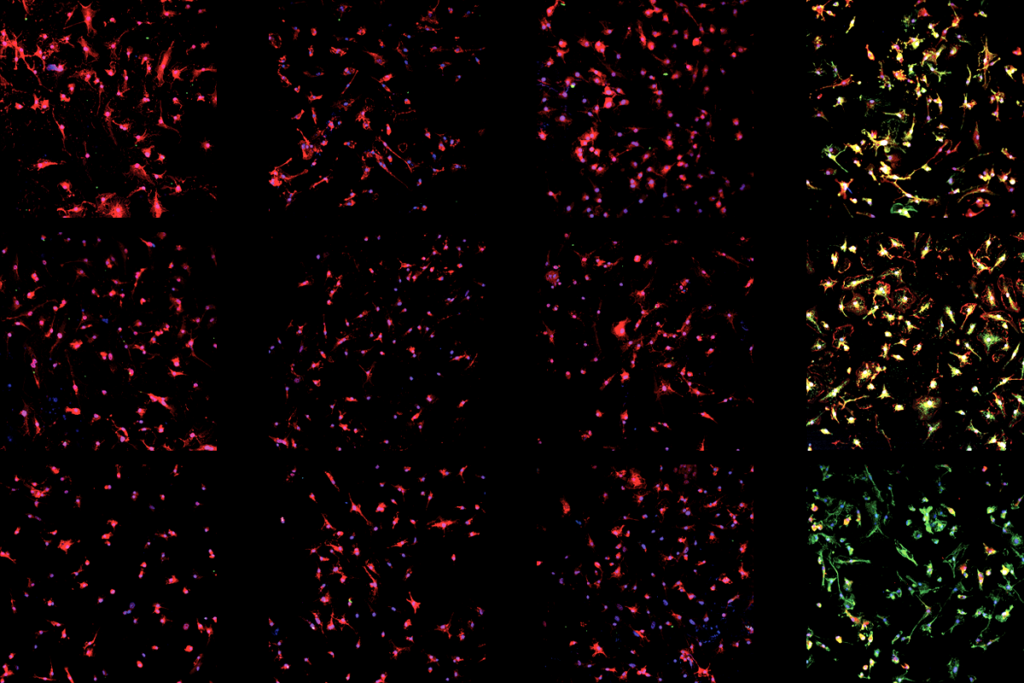

The impetus to create the space was clear. The setup, paired with wireless electrodes inserted in the bats’ hippocampus, has helped the team demonstrate, for example, that place cells encode a flying bat’s current, past and future locations. Also, a mountain of evidence suggests that the identity, sex and stress levels of human experimenters can influence the behavior of and brain circuit activity in other lab animals, such as mice and rats.

Now Yartsev and his team have proved that “experimenter effects” hold true for bats, too, according to a new study published last month in Nature Neuroscience.

The presence of human experimenters changed hippocampal neuronal activity in bats both at rest and during flight—and exerted an even stronger influence than another fruit bat, the study shows.

The team expected that humans would influence neural activity, Yartsev says, “but we did not expect it to be so profound.”

The results are an important reminder to account for experimenter effects during neural recordings, Yartsev says. This accounting can be done by measuring the position and behavior of the human, and regressing it out or controlling for it later during analysis, he says. “[But] I think the best approach is to avoid having humans in the room.”

I

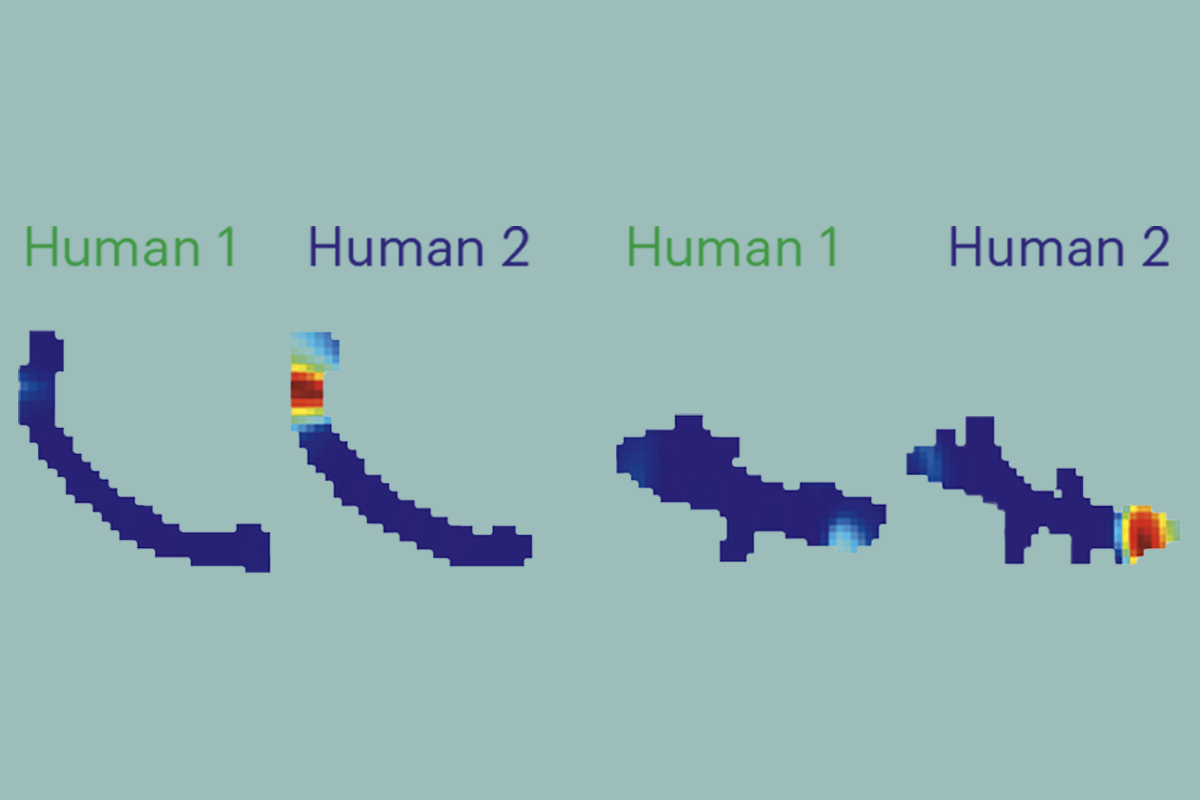

n the new study, two members of Yartsev’s team stood at different locations in the bat flight room, each offering the animals a drop of banana smoothie on an outstretched palm. Both wore gloves of a similar size to minimize variability, and they swapped locations every five minutes throughout the experiment. Two bats roosting on the other side of the room could spontaneously fly to either person.The identity of the person at the landing site influenced the firing of almost half the recorded neurons, the study shows. Even after the team removed one bat, more than 40 percent of the remaining bat’s neurons still had different firing activity depending on which person was present near the landing site, indicating that the coding for humans is more robust than for another bat.

The people’s movement also influences neural activity in stationary bats, the team found. A subpopulation of neurons—distinct from those modulated during flying—carries information about the position and identity of human experimenters in bats that are resting.

The findings agree with previous work that showed that bat hippocampal cells represent the position of other bats and inanimate moving objects, says David Omer, assistant professor of neurophysiology of cognitive processes at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who worked on that study but was not involved in the new one. “It is important to record physical parameters involving the experimenter,” to untangle the contribution of different factors in neural representation, Omer says. Scientists could also design behavioral tasks requiring minimal experimenter involvement, he adds.

Bats need a sophisticated apparatus to sense potential predators, so “it would be very surprising if the bats are oblivious to humans,” says Julio Martinez-Trujillo, professor of physiology and pharmacology at the University of Western Ontario, who was not involved in the study.

The presence, identity and actions of human experimenters are likely to be represented in the hippocampal neurons of other lab animals, such as mice and rats, according to Yartsev, Omer and Martinez-Trujillo.

Yartsev says his team is “fully satisfied” with their decision to move toward human-free experiments involving bats, and he plans to continue to do so for future studies. “The results reinforce the importance of studying natural behaviors,” he says, “and letting animals behave spontaneously as they would.”