This past January, Ellen Leschek started getting “a lot of calls and emails” from people who, for different medical reasons, had received pituitary human growth hormone before its synthetic form was introduced in 1985.

The hormone these people had received came from human cadavers—so they knew they were at an increased risk for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), which can be transmitted through medical procedures, or iatrogenically, via misshaped prions. But now they had a new concern, they told Leschek, who leads surveillance of the National Hormone and Pituitary Program—namely, that they might also be at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

The people calling Leschek, who is also a pediatric endocrinologist at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, had all read a study published in Nature Medicine that same month. The study described eight people from the United Kingdom treated with cadaver-derived human growth hormone who had allegedly contracted Alzheimer’s disease as a result.

But when Leschek examined the report, she says, she concluded that the January paper did not provide enough evidence that the eight cases are Alzheimer’s disease. She teamed up with three Alzheimer’s experts and a National Institutes of Health neurologist to detail their objections to the original findings, in a Perspective article published last month in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Leschek and her co-authors agree that one person described in the January report may be exhibiting preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. And because five of the eight people are still alive, she notes, the researchers could have gotten more data. “There was actually room for them to more definitively determine whether or not [the eight cases] had Alzheimer’s, who met the criteria,” she says, “but they didn’t.”

T

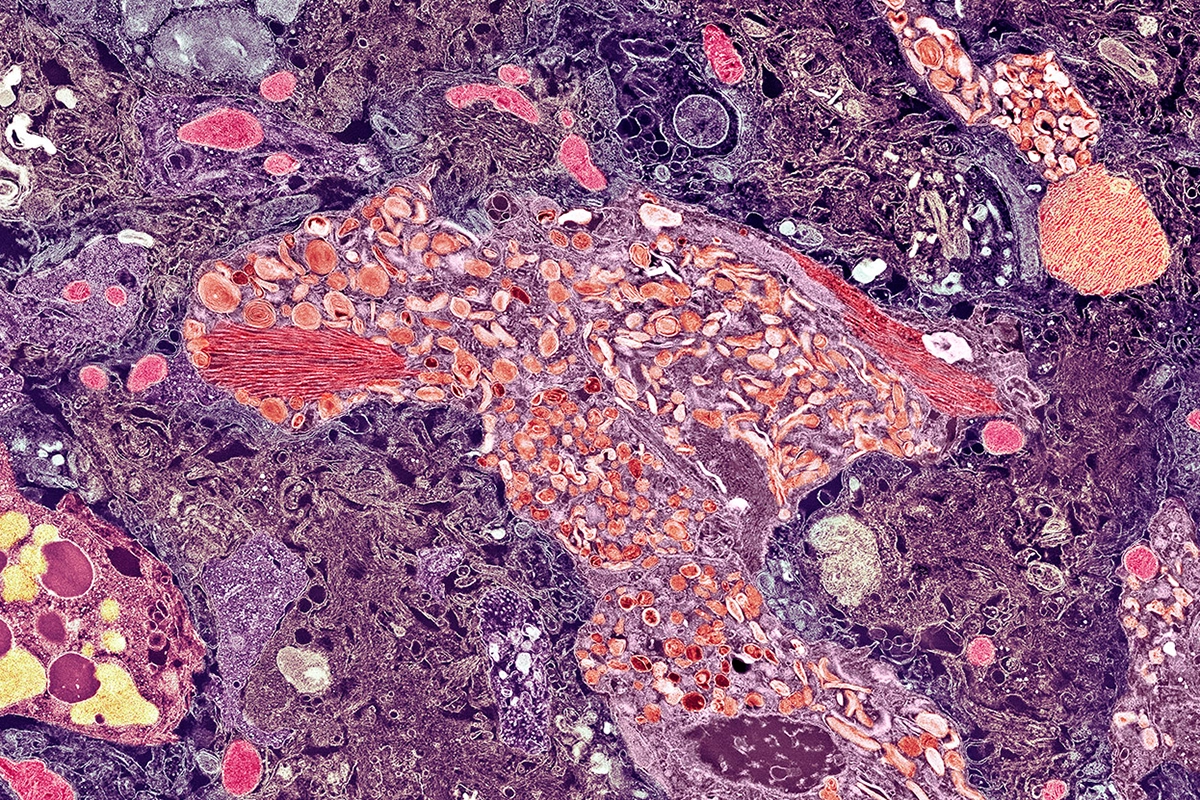

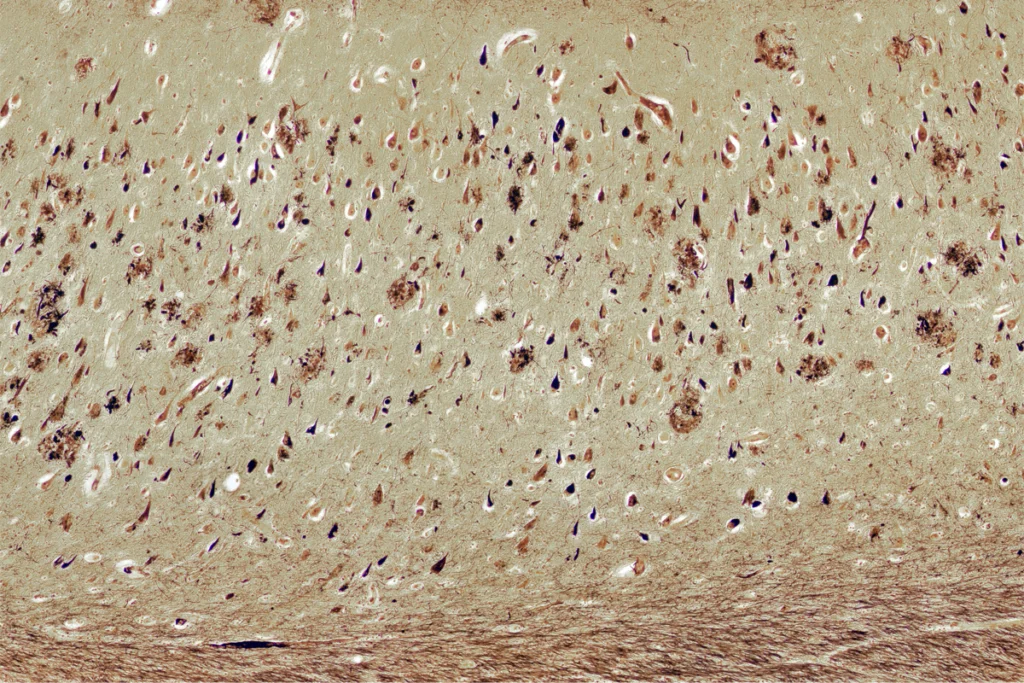

he connection between cadaver-derived growth hormone and CJD—a link now credited with more than 250 cases worldwide—was first found in 1985. But the purported Alzheimer’s link was discovered “unexpectedly” about a decade ago during the autopsies of eight people who died from CJD, according to a 2015 study.In addition to having CJD, four of the eight had amyloid beta in their gray matter and vascular amyloid beta pathology, leading the authors to hypothesize that “seeds” of the Alzheimer’s-linked protein can be transmitted under certain circumstances. Archived growth hormone samples showed high levels of amyloid beta in a subsequent Nature analysis led by John Collinge, director of the MRC Prion Unit and University College London Institute of Prion Diseases, who co-led the 2015 investigation.

The January Nature Medicine paper, also led by Collinge, described eight people who developed both early-onset dementia and Alzheimer’s-related “biomarker changes” and who were among a cohort of more than 1,800 people treated with cadaveric growth hormone before 1985. (Collinge was not available for comment before the publication of this article.)

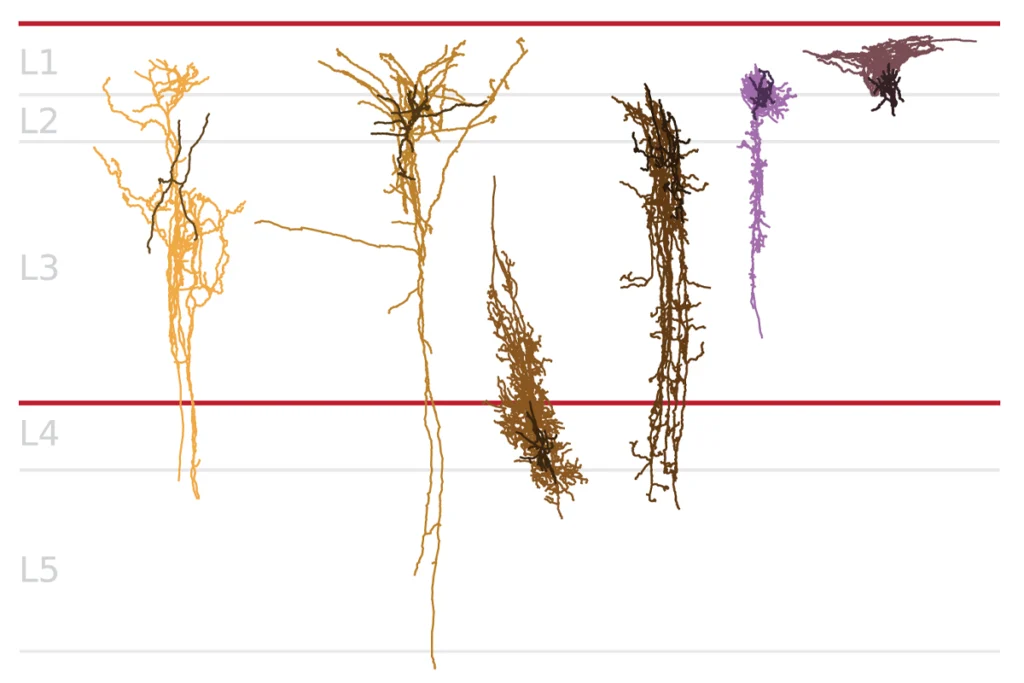

But none of the eight possess “convincing” tau pathology necessary for an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Leschek and her colleagues counter in their new Perspective article—and two were not even tested for it. Also, they say, Collinge and his colleagues analyzed only three of the eight for gene variants linked with early-onset Alzheimer’s, which none possessed.

“The criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease requires the presence of amyloid and tau, and this diagnosis can be made with autopsy material or clinically. The cases in this report—with one exception—lack that evidence,” Bruce Miller, director of the Memory and Aging Center at the University of California, San Francisco and co-author of the Perspective piece, wrote in an email to The Transmitter.

Based on both animal data and prior human work, “it’s plausible that at least some of these cases do have iatrogenic Alzheimer’s disease, and the most likely cause is probably [amyloid beta] seeds,” says Lary Walker, emeritus associate professor of neurology at Emory University School of Medicine, who was not involved in either study but co-authored a News and Views article that was published with the Nature Medicine study in January.

Walker points to previous evidence that cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a condition that often accompanies Alzheimer’s disease, can be transmitted “under these extraordinary circumstances.” Another paper, he says, shows that it may take decades for tau pathology to show up after exposure to these amyloid beta seeds. It is “sort of a general theme in what little has been published on this so far, that you have to wait a long time before you start seeing that amplification of [amyloid beta] deposition into subsequent tauopathy.”

T

here are several alternative explanations for the cognitive impairment in the eight people described in the January Nature Medicine paper, Leschek says, adding, “This is a very complicated population.” People who got these hormones may have had pituitary tumors, which means they also needed brain surgery and radiation—possibly leading to “quite a lot of neurologic damage” and other forms of dementia, she says.Still, the potential for Alzheimer’s disease to be transmitted in health-care settings has “a huge public health implication, because if it’s that transmissible, then it changes the way we handle neurosurgical procedures,” Leschek says.

Walker agrees that the people in the cadaver-derived growth hormone databases are “an imperfect dataset,” and because of this, he says, “I don’t think it is going to be possible to ever develop definitive evidence in humans that Alzheimer’s disease is transmissible in this way.” But hormone treatments are no longer derived from cadavers, he says, and so “this is not by any means a public health crisis.”

The January paper “is a reminder that we need to be careful any time we invade the human body, either with surgical instruments or therapeutic agents,” Walker adds. “I agree with the idea that we need to be critical in looking at these sorts of reports, but I also think they tell us something important about Alzheimer’s disease.”