Carol Jennings, whose family’s genetics informed amyloid cascade hypothesis, dies at 70

Her advocacy work aided the discovery of a rare inherited form of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease and helped connect affected people with researchers.

Carol Jennings, a former schoolteacher whose family history and advocacy efforts helped lead to the discovery of an inherited form of Alzheimer’s disease, died last month at age 70. The cause of death was Alzheimer’s disease, according to the Alzheimer’s Society.

Several members of Jennings’ family carried a variant in the gene that encodes the amyloid precursor protein (APP), according to a 1991 study. Those findings contributed to the amyloid cascade hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease, proposed by the study’s lead investigator, John Hardy, in 1992.

“She was a remarkable person,” says Hardy, professor and chair of molecular biology of neurological disease at University of College London.

Hardy says he first encountered Jennings in the mid-1980s after he and his colleagues placed an advertisement in the Alzheimer’s Society newsletter seeking families with multiple cases of dementia. Jennings responded in a series of letters to the researchers, explaining that her father, Walter Bexon, and four of his nine siblings had recently been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease within a three-year span. All were between 54 and 58 years of age.

At the time, the disease, which is characterized by cognitive decline, was thought to be a symptom of old age—not genetics—Hardy says. “But she just looked at her family tree.”

J

ennings, then a part-time schoolteacher and the mother of two young children in Nottingham, England, rallied members of her extended family to join the study. She convinced many of them to give blood samples and, eventually, donate their brains after death to the research program—at a time when organ donation was in its infancy, says Stuart Jennings, Carol’s husband.Thanks to her efforts, Hardy and his colleagues were able to analyze DNA samples from 39 people in Jennings’ family, including her father, all of his siblings and 3 cousins, 19 of their children and spouses, and 7 more-distant relatives. Affected family members all carry a single DNA letter change in the APP gene on chromosome 21, the team found. The children of a parent who carries the variant have a 50 percent chance of inheriting it themselves.

Jennings chose to not get tested for the APP variant following its discovery in her family, her husband says. She began working for the Alzheimer’s Society and other dementia charities to organize research presentations for families of people with a related condition called frontotemporal dementia, and to present her own family’s story at pharmaceutical and research conferences, he says.

“She inspired connections between individuals afflicted with Alzheimer’s and researchers searching for a cure,” says Nicole Rust, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Jennings underwent annual MRI scans and lumbar punctures for research for more than 25 years, her husband says, and their son participates in the same studies as his mother did. The longevity of the Jennings family’s commitment to Alzheimer’s research is a testament to Carol Jennings’ legacy, which began with her letters and “continues to live on and on,” Rust adds.

In 2012, Jennings was formally diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at age 58, and her health began to decline in 2017, her husband says. In 2022, the BBC announced an upcoming documentary about the Jennings family, titled “Family 23,” referring to the name given to the Jennings family in the 1991 study.

Jennings continued to live at home in Coventry, England, until her death, after which her brain and spinal cord were donated to research, her husband says. This final wish from Jennings, he adds, comes from the decades of “rapport and trust” built between the research team and her family.

Recommended reading

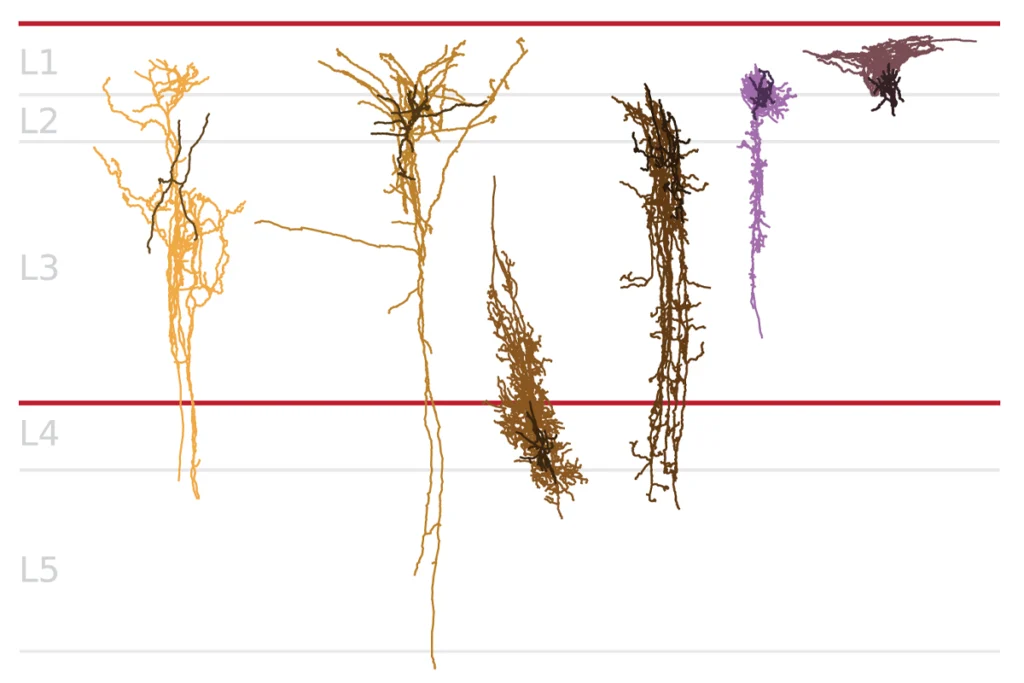

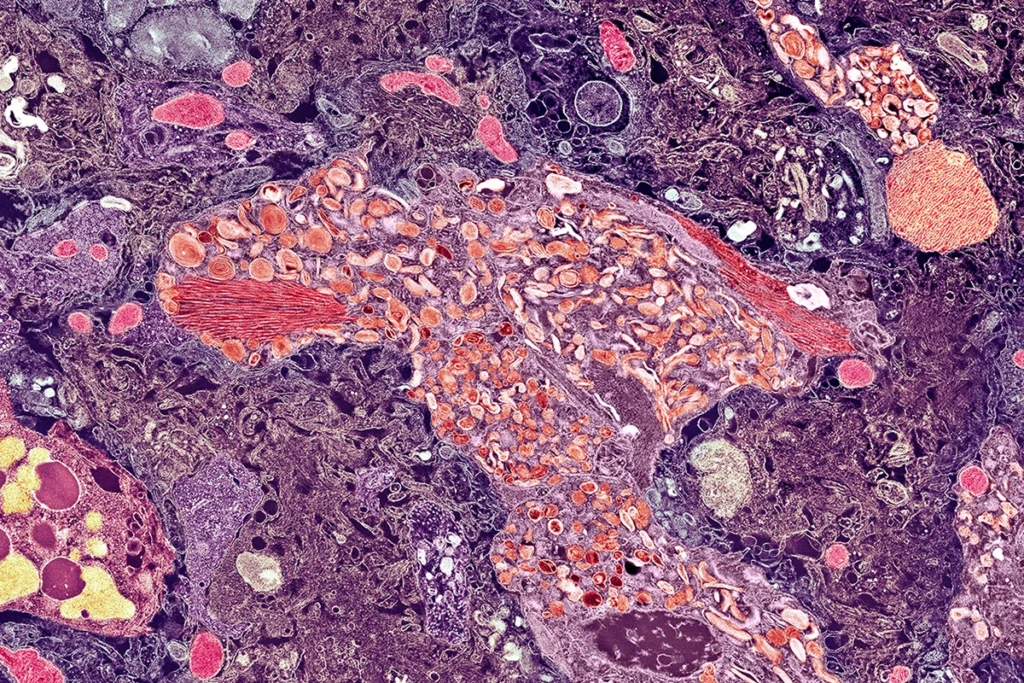

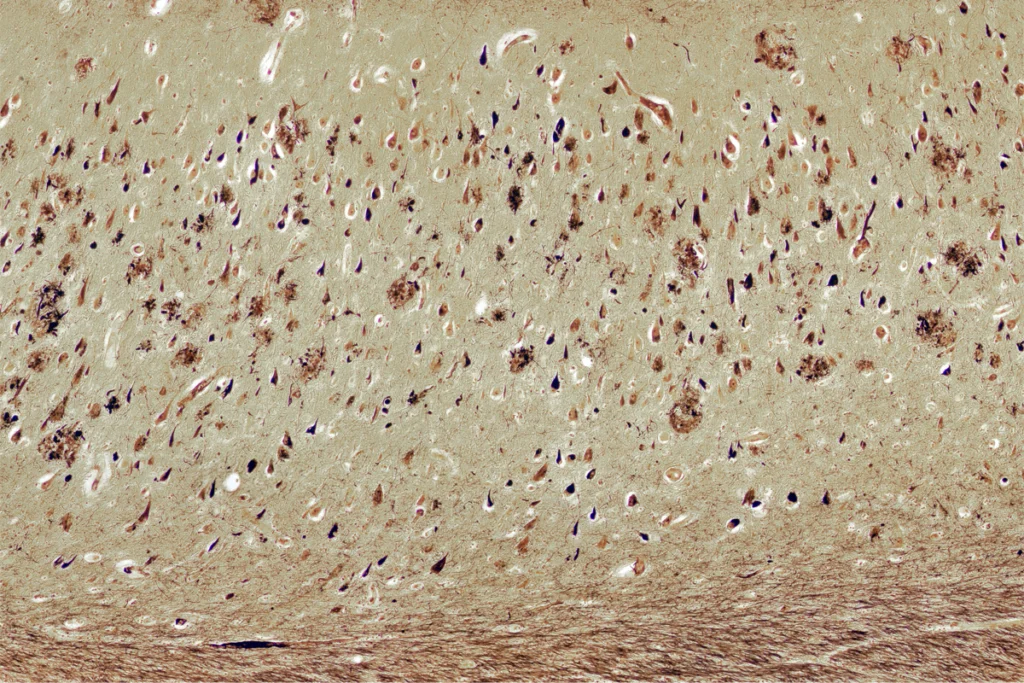

Early trajectory of Alzheimer’s tracked in single-cell brain atlases

Skeptics challenge claims of Alzheimer’s disease transmission via growth hormone

Reviving ‘inside-out’ hypothesis of amyloid beta to explain Alzheimer’s mysteries

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more