Over the past 20 years, our understanding of the brain and how things can go awry in disease has exploded, driven by advances in our ability to visualize, record and manipulate discrete circuits in the brain; in molecular biology and genetics; and in funding programs, such as the BRAIN Initiative, to bolster brain research. But much of this knowledge has not trickled down to nonscientists. As a consequence, the knowledge gap between scientists, health-care professionals, policymakers and people struggling with mental health conditions is growing. The unfortunate outcome of this situation is slow translation of basic science to new treatments, and a general lack of knowledge about the most effective treatments available.

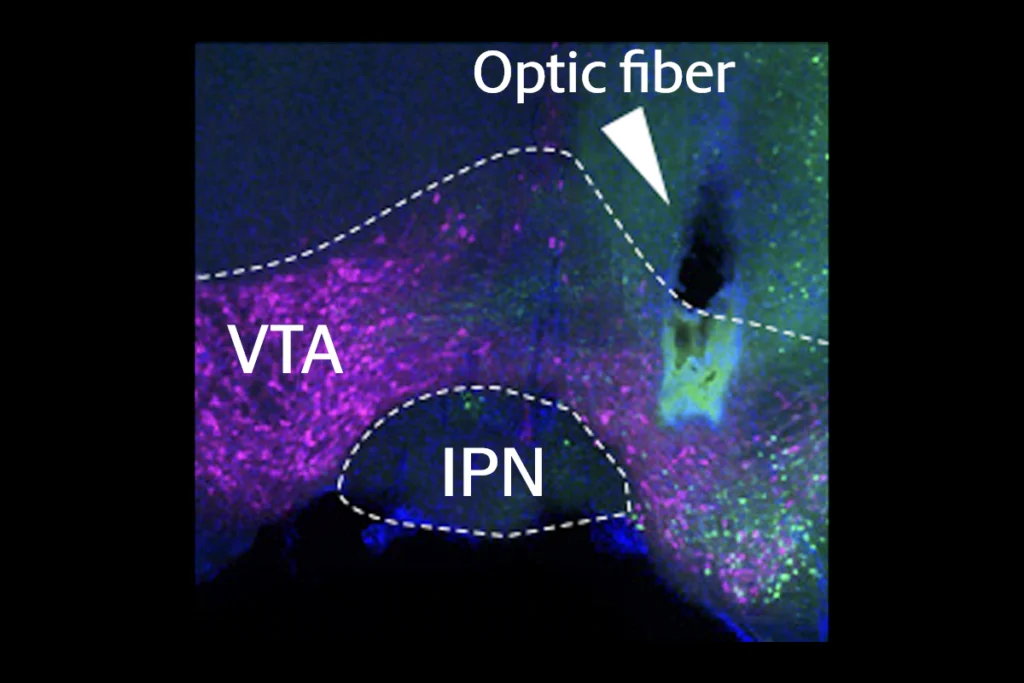

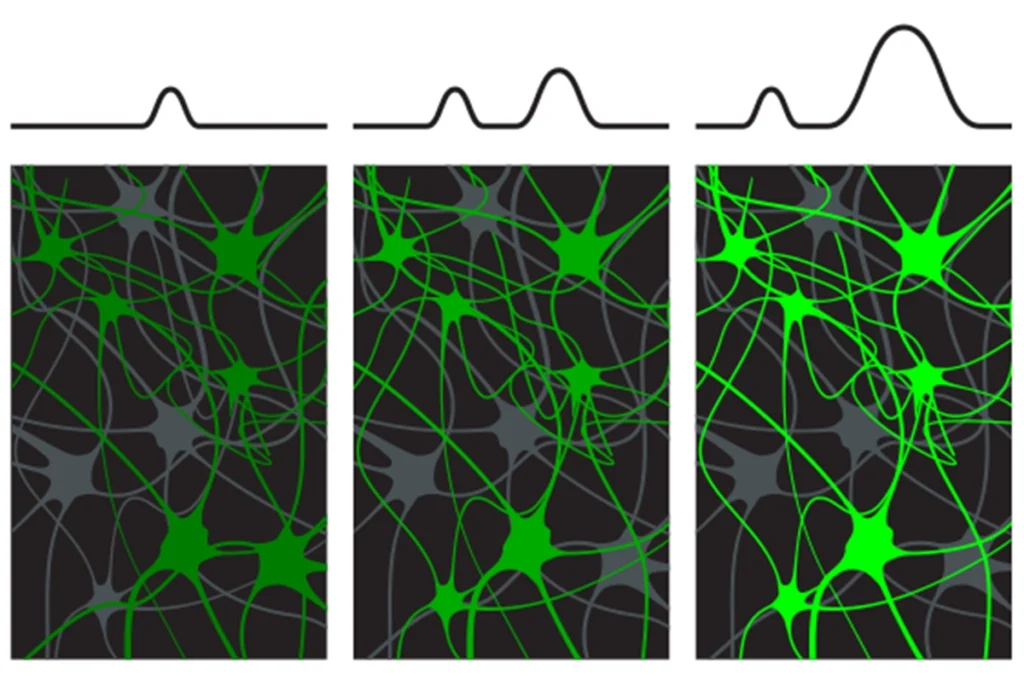

Addiction science offers a prime example of this disconnect. Basic neuroscience research in diverse animal models has revolutionized how we view addiction. We now know that alcohol and other drugs of misuse have profound effects on the molecular mechanisms that influence reward, memory and decision-making circuits in the brain: Their repeated use alters gene expression, modifying cell function and circuit activity, ultimately leading to the compulsive seeking behaviors typical of people with a substance use disorder.

Understanding the strong biological basis for these behaviors has provided new avenues to develop more effective treatments and helped reduce the stigma around addiction. But despite years of research demonstrating that the use of alcohol and other drugs alters brain gene expression and cell and circuit function across species, this knowledge appears to be relatively restricted to the scientific community. This is why we believe the scientific community needs to spend more time and effort advocating for basic addiction research.

H

ow can we, as basic neuroscientists, best advocate for research? One of the most important things we can do is to talk about our research in our everyday lives and explain why we think it’s so valuable. By sharing our motivation, we create a personal context for why our work matters and make it more accessible at the same time.For example, one of us, Omar Abubaker, lost his son to addiction and wants to ensure that no other parent goes through the unbearable grief he experienced. He aims to close the gap between what neuroscience has accomplished in defining addiction and how the next generation of health-care professionals is educated about addiction, ensuring that treatment improves.

Karla Kaun was born into a community that had been home to one of the longest-running residential boarding schools for Indigenous children in Canada and, as a teen, lived in a small mining town in the northern Rocky Mountains. These experiences taught her how colonization and remote conditions affect the culture and health of a community through cycles of addiction and abuse, motivating her to understand the causes of addiction and help make the latest research on addiction accessible to all.

Eric Nestler trained in basic neuroscience and then became a psychiatrist. He was drawn to study addiction because of the validity of available animal models, and the opportunity they provide to understand the biological underpinnings of mental disorders.

Our “backstories” help us to explain our research to people who don’t have strong scientific backgrounds. That outreach not only improves our communication skills but, in the case of addiction, can also help shift the narrative from it being a matter of willpower to a treatable disease. This reframing can empower people with a substance use disorder by providing hope that their condition can be overcome with the right treatment, care team and support system.

Another way to advocate for neuroscience research is for us to get involved in our local communities—by giving public lectures, participating in community events and science fairs, performing outreach activities in schools, and even volunteering at local soup kitchens and shelters. No matter what activities you participate in, when it comes to outreach, you are a representative of the science you study and can help shape the narrative around mental health.

C

ommunity outreach further provides an opportunity to advocate for the importance of animal models in basic research. Addiction research employs a diversity of animal models, from nematodes to nonhuman primates, and each model offers a different level of investigation and mechanistic understanding. It’s important for people to recognize that animal research has enabled many key discoveries in mental health conditions. And only by integrating information from all animal models can we gain a truly holistic understanding of the mechanisms that underlie how the brain functions in health and disease.Outreach to health-care professionals is also enormously important to ensure that they understand the science of addiction and recognize the most effective treatments. Despite widespread alcohol and drug use in the United States—with consequences for cardiovascular, respiratory, immune, liver and brain disease—many physicians and nurses are not taught about the mechanisms behind addiction or about the most effective treatments for substance use disorders. The information in typical undergraduate textbooks is more than 50 years old, and undergraduate students often don’t get to learn where the field of addiction is going. A challenge for us, as basic scientists, is to guarantee that the future generation of health-care professionals, entrepreneurs, journalists, law-enforcement professionals and policymakers understands the importance of addiction and mental health research.

Advocacy can also help overcome the challenge of translating basic neuroscience research into effective treatments for diseases, including substance use disorders. The complexity of the brain has traditionally prohibited us from gaining a deep understanding of how we can address conditions such as depression, anxiety and addiction. But over the past few decades, basic research has revealed new insights into how the brain works at a molecular level, providing novel ways to think about treatments.

Our new neurobiological understanding has the potential to lead to improved biometric diagnostic tests and more targeted treatments with fewer side effects. We are discovering that the mechanisms driving mental health conditions can vary from person to person, and we are at a point where we can start developing personalized medical treatments, much how we tailor treatments for diabetes and heart disease.

But for this to happen, the groups that define medical treatment policies, provide funding for research and treat these conditions have to see the merit in supporting this research. And to that end, advocacy is a skill that all basic scientists should learn and hone.

Talking about our science with other scientists generates new ideas and helps the field evolve, but it does little to inform the public. Opening lines of communication within our local communities—with students, health-care workers, patients, policy experts or neighbors—will help us understand people’s needs and identify barriers so that we can work to address them. Like lawyers learning to present a case to the court, scientists should learn to educate nonscientists about their findings. Effective communication and negotiation skills are essential to influence policies and advocate for equitable access to resources. Only by stepping outside of our comfort zone and developing these skills can we update the public’s knowledge to reflect the current scientific understanding—a shift that promises to lead more people to treatment and ultimately to more effective treatments for mental health conditions.