When Mala Murthy and Sebastian Seung of Princeton University saw high-resolution 2D electron microscope images in a 2018 Cell paper, they decided to try to build a fruit fly connectome with that dataset. Funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health BRAIN Initiative, Murthy and Seung used the electron microscopy data to launch the work that resulted in FlyWire, a nine-paper package published in Nature in October 2024. The work made international headlines for its novelty and ambition.

Not long ago, the length of the author list on the flagship FlyWire paper also would have been newsworthy: 46 researchers, including Murthy, Seung and first author Sven Dorkenwald. Neuroscience research has long been driven by individual labs and individual investigators, but today it is increasingly becoming a team sport similar to the FlyWire work—a 2024 preprint describing a study of hundreds of thousands of neuroscience papers published worldwide between 2001 and 2022 found a consistent rise in the number of authors per paper in nearly every country examined.

There were 66 Nature Neuroscience papers in 2023 that had double-digit author counts, with the longest author list for that year comprising 209 names. The causes of this shift are related to technology breakthroughs that have allowed for the generation of massive datasets, as well as the general maturation of neuroscience, which is catching up with the large-scale, collaborative efforts put forth in other fields. The dual landmark papers in 2001 revealing the first draft of the Human Genome Project boasted 249 authors (in Nature) and 274 authors (in Science), and a fruit fly genome paper published in 2015 had more than 1,000. In physics, a 2015 paper providing an estimate of the mass of the Higgs boson listed more than 5,000 authors, thought to be a record.

But researchers say long author lists are also raising questions about what kind of work is most productive for neuroscience and how to best parcel out credit. A stack of author names can diffuse “responsibility for what’s in the paper,” says neuroscientist J. Anthony Movshon of New York University. “We’re going to a place where it’s very hard to establish whose work you’re actually reading.”

M

any of the early big discoveries in neuroscience were announced as two-author papers: Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley were the first to model action potentials, in the squid axon; James Olds and Peter Milner discovered reward centers in the brain; and David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel unveiled connections between neurons and visual perception.The questions being asked then were simple enough to be tackled by two people. Shari Wiseman, chief editor of Nature Neuroscience, says today neuroscience is being driven by “big questions” that require “big, ambitious undertakings,” and that is reflected in the higher number of authors.

An examination by The Transmitter found that from 1996 to 2023, the average number of authors on papers published in the Journal of Neuroscience grew from 3.9 to 6.3. Over that same period, Neuron’s average number of authors per paper increased from about 4.6 to 8.6. Nature Neuroscience has followed a similar path: In 1998, the journal’s average number of authors per paper was 4.2, but by 2023, the average was nearly 9.

The concern around long lists of authors might be traced back to 2001, when the term “hyperauthorship” is thought to have been coined by information scientist Blaise Cronin. That concern has been applied to neuroscience as multiple consortiums and broad, collaborative science have taken hold to investigate large questions. The International Brain Laboratory (IBL), which is funded by the Simons Foundation, The Transmitter’s parent organization, launched in 2017 and includes 22 labs investigating brain circuits underlying complex behavior. The BRAIN Initiative was established in 2013 to better understand the brain. And the Allen Institute for Brain Science, set up in 2003, entered a new phase in 2012, pursuing research to decipher the brain’s neural code.

“Big science is really needed to tackle the complexity of the brain,” says Hongkui Zeng, director of the Allen Institute for Brain Science.

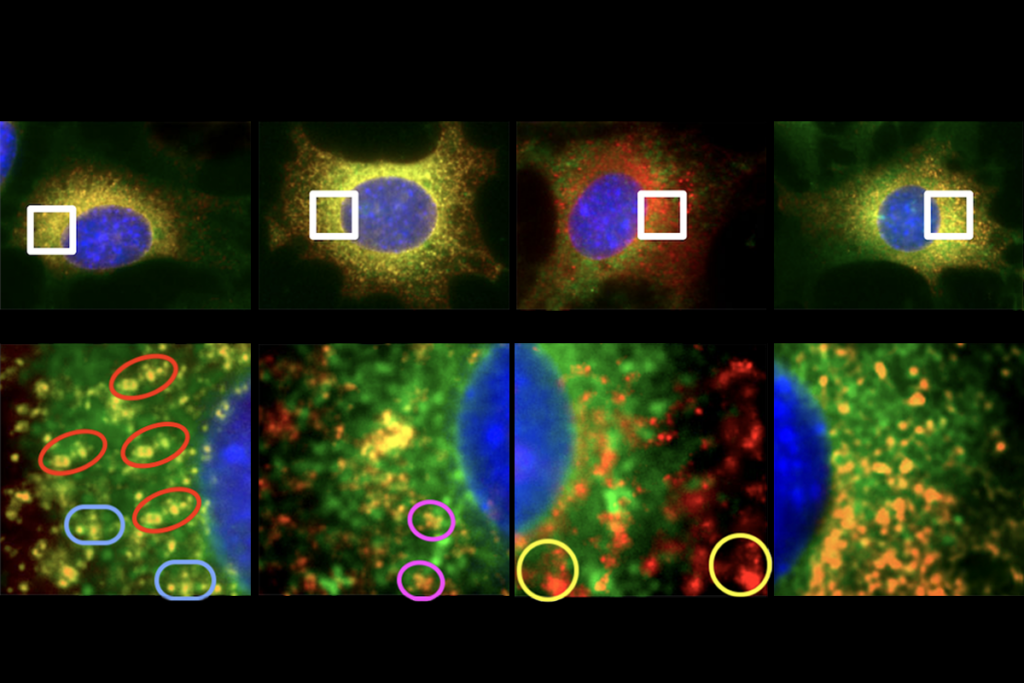

As the size of datasets grew, so did the number of people needed to work with them, and the expertise required to use new techniques. An example is the October 2024 work from Jeremy Herskowitz’s lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine. He and his colleagues established a molecular basis for brain connectivity by studying protein concentrations in 98 human brains, pre- and postmortem. The research required analysis of functional MRI and structural MRI data, analysis of proteins in postmortem brain samples using a mass spectrometer, analysis of the dendritic spine morphology in those samples, and RNA sequencing. The paper was published in Nature Neuroscience, and the author list swelled to 20, including students from Herskowitz’s lab plus a team from the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, including first author Bernard Ng, whose patients were the source of the data. Every aspect of the work must be done by an expert, Herskowitz says. “And there’s virtually no overlap.”

Similarly, the FlyWire connectome consortium is spread across labs and continents. “Building a complete map of the [fly] brain, that’s a pretty pie-in-the-sky idea and definitely takes a large, coordinated effort to pull it off,” Murthy says. The FlyWire team, for example, included computer scientists, software engineers, experts in neural networks, biologists and anatomists, as well as community organizers to keep the effort on track. To avoid mistakes, many pieces of the plotted connectome, such as the segmentations of neurons, had to be examined by a human, Murthy says. “There was no way we could do it on our own.”

P

h.D. students need publications in order to advance. In particular, there is a “strong pressure to publish something great,” says Dorkenwald, who is now a Shanahan fellow for the Allen Institute and the University of Washington. It can be harder to stand out when part of a big collaboration, but collaborations can also open doors. A “young scientist” working in a large-scale effort has an opportunity “to do analysis using this data that they would not have otherwise by doing their own experiment,” he says.This need to publish has dovetailed with a new desire in science to properly acknowledge all contributors. “We have a very supportive spirit,” Zeng says. “Even though a paper may be mainly spearheaded by just a few people, we still include many of the technicians and other managers who contribute to the work.”

Yet there are ways of honoring effort without resorting to what Movshon calls “decor authorship.” That can include the acknowledgments section of a paper, where the authors note those who provided integral feedback or helped edit figures. For the FlyWire consortium, every person who contributed a significant number of corrections or labeled a cell (all 292 of them, including citizen scientists) is named on the FlyWire website, but the authorship itself is more stringent: The 46 named authors on the first paper include the team at Princeton University that led the project, with Dorkenwald as first author because he co-developed the infrastructure for proofreading and helped lead the community effort to complete the dataset. Seung and Murthy are listed as senior authors. Some of the other named contributors come from the laboratory of Gregory Jefferis at the University of Cambridge, who was a key collaborator.

Other organizations have developed their own solutions to handle credit. The IBL decided that “platform projects”—large data efforts across labs—would list the IBL itself as the first author. The idea was borrowed from CERN, the physics research center based in Geneva, which generally does not include named authors at the top of papers. “I think it was not everybody’s first choice,” admits Hannah Bayer, executive director of the IBL, though the IBL compromised by adding a list of contributors alphabetically after the IBL as first author, and then listing contributions in detail at the end of the paper. In the IBL’s 2021 eLife paper about standardized and reproducible decision-making behavior in mice, for example, there are two full pages listing “author contributions” broken into categories and subcategories—24 in all—including methodology, resources and investigation.

In addition, the IBL creates a supplementary table in its papers, in which researcher names run vertically, and credit taxonomy is represented horizontally. Boxes are colored purple for categories in which some person contributed, and a gradient from light to dark purple emphasizes how much. “We’ve tried a bunch of different ways” to acknowledge effort, Bayer says, “but it’s pretty messy.”

Indeed, a postdoc with a “bunch of dark purple squares” still isn’t seen in the interview process as “being as intellectually [and] scientifically independent as one would expect,” Bayer says. In other words, there has not yet been the necessary cultural shift to recognize the kinds of work that go into team science. That’s why the IBL has a separate category of paper called “personal projects” that follows a more standard structure: The first author is the person driving the research, the principal investigator is listed last and the IBL somewhere in the middle.

In time, most neuroscientists believe that as longer lists of authors become the norm, the field will adjust. “As people who are making decisions about fellowships and grants and hiring recognize that science is more of a team sport, hopefully they [will] be better able to recognize the value of, let’s say, middle authorship,” Wiseman says.