Gerry Rubin loved his time as a Stanford University postdoctoral researcher. The two years were intense, he admits—he worked up to 80 hours a week in the lab, for pay that ended up being less than minimum wage. But he was 24, staying out of debt and could afford a car and a one-bedroom apartment (with a pool) in Palo Alto, California. And anyway, he was at Stanford, working down the hall from Nobel Prize winners, creating one of the first clone libraries. It felt like a dream.

In 1976, fresh off that postdoc position and still only 26, Rubin won a faculty position at Harvard Medical School, joining the nearly 72 percent of recent biomedical postdocs in the United States who were working in tenured or tenure-track positions that year. “No one felt exploited,” Rubin says, because “we felt it was a trade-off. We were learning new stuff, and then we were out the door.”

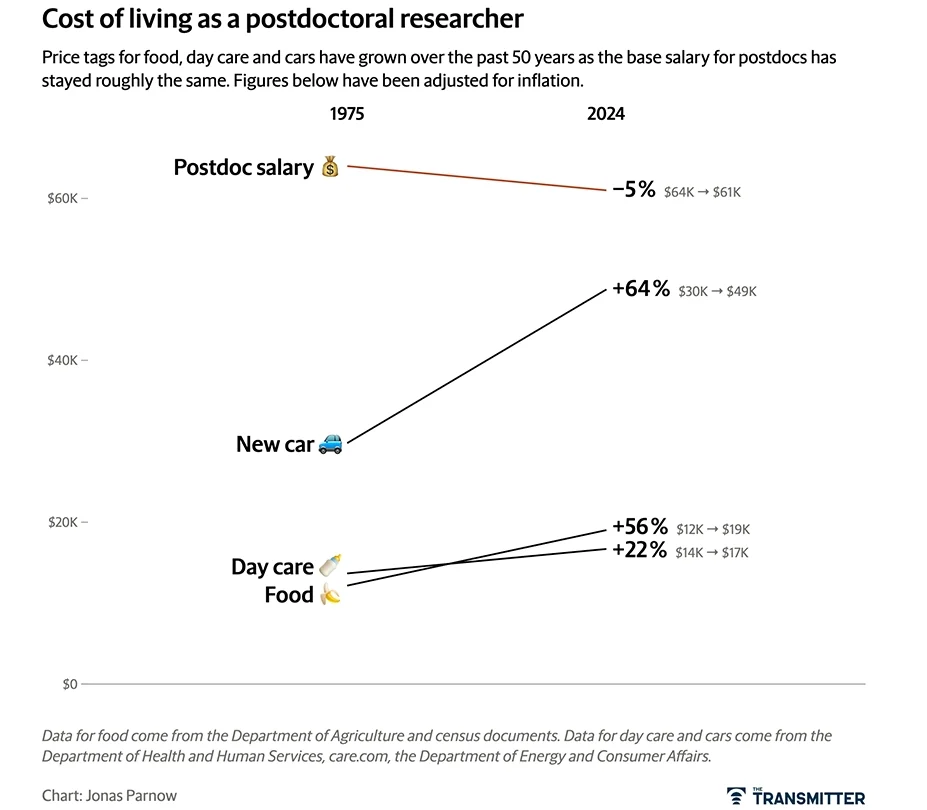

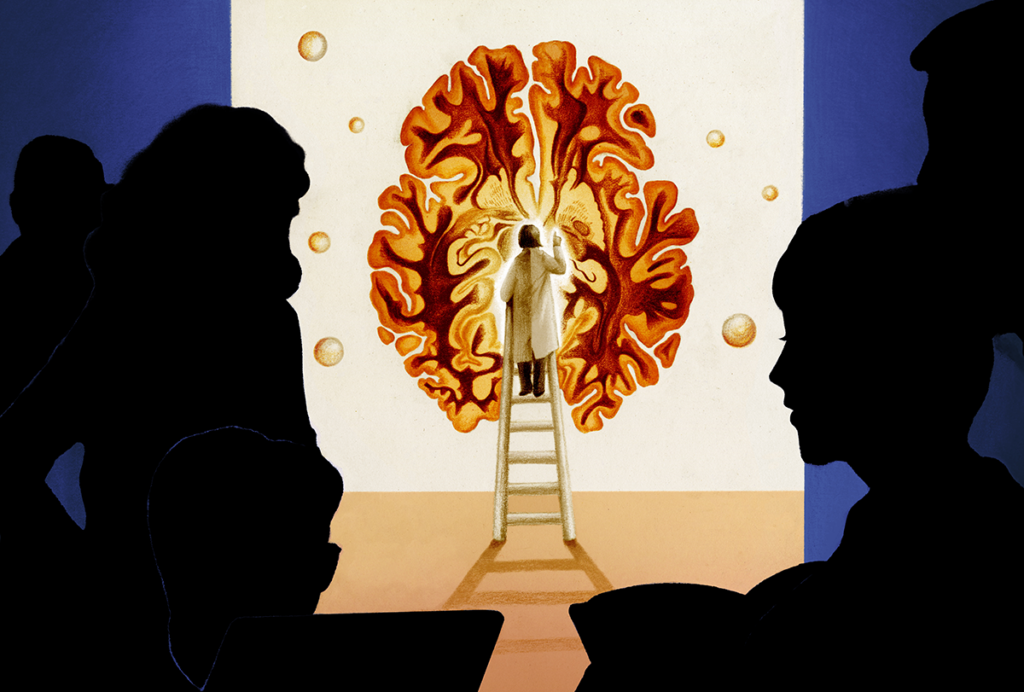

Things have changed a lot in 50 years. Rubin is now senior group leader at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus, where his group studies neurobiology, and today postdoctoral positions often last three times as long as Rubin’s did. Also, trainees are coming to them later than he did—a typical postdoc now joins a lab in their 30s, a time when many hope to be starting families. The annual stipend from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) for a new postdoc was $10,000 in Rubin’s time. That’s about $64,000 in today’s money, which compares with the current base wage of $61,008. But these days, only about 26 percent of academic postdocs in the life sciences land faculty jobs.

The effects of rising living costs amid plummeting job prospects and stagnant salaries are fueling what some are calling a talent leak in basic neuroscience, and beyond. No longer viewed as an intense but intellectually rewarding training opportunity for future principal investigators (PIs), postdoctoral fellowships are now seen by many as cheap, long-term labor for established researchers. And a growing number of young scientists want out: The National Science Foundation does not break down postdocs beyond the categories of science and health, but those ranks dwindled from 55,748 to 54,415 in the U.S. between 2012 and 2022—about a 2 percent drop—after decades of growth. In the same time frame, the number of applicants for the NIH’s Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award postdoctoral fellowship dropped from 2,284 to 1,438—down by 37 percent. In 2023, the number of applicants dropped by another 17 percent to just 1,188.

The decline feels outsized in disciplines such as computational neuroscience, where tech companies investing in artificial intelligence have lured Ph.D.s away from academia with six-figure salaries, flexible work arrangements and generous 401Ks. “Computational neuroscientists now have opportunities that they didn’t have 5 or 10 years ago,” says Andrew Lo, Charles E. and Susan T. Harris Professor of Finance and Director of the Laboratory for Financial Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Sloan School of Management. “There is a porous membrane between academia and industry, particularly in the area of computational neuroscience.”

Kaela S. Singleton, who earned a Ph.D. in the interdisciplinary program in neuroscience at Georgetown University and is now director of grants management at the nonprofit organization Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, agrees that neuroscience is particularly vulnerable. “You have this highly skilled group of thinkers, leaders and problem solvers working through a system that hasn’t been updated in eons, and they’re outgrowing it,” says Singleton, who is also president of Black In Neuro. “It feels like other industries are recognizing that talent, building new opportunities or making folks offers they can’t refuse.”

It has been bad enough that, in late 2023, the NIH Advisory Committee to the Director Working Group on Re-Envisioning NIH-Supported Postdoctoral Training produced a report with recommendations for “improving the postdoctoral experience for both the postdoctoral scholar and the broader biomedical ecosystem.” President Trump’s freeze on federal funding for postdocs receiving National Science Foundation grants—rescinded, but with lingering effects as of press time—has only heightened the sense of uncertainty for researchers.

In neuroscience circles, it seems nearly everyone agrees there is a problem; the question is whether academia is listening.

N

euroscience’s supply-and-demand problem was hinted at before even Rubin joined the postdoc ranks. In 1969, a study conducted by the National Research Council nicknamed postdoctoral fellowships the “invisible university”—an underrecognized and transient workforce whose numbers were growing. In 1976, MIT physicist Lee Grodzins predicted that the relative dearth of faculty positions would lead some strong Ph.D.s to ditch the postdoc path in favor of industry jobs.Between 1979 and 2022, the number of graduate students in science and health fields in the U.S. more than doubled, from 285,770 to 622,534, and the number of postdocs nearly tripled, from 17,034 to 54,415. The number of junior faculty jobs in the life sciences also grew in the time period, but only from 11,300 in 1981 to 22,400 in 2021. This has left many postdocs in a kind of limbo, languishing for an extra year (or two, or three, or four), hoping to publish the paper that makes them a more competitive applicant for the few available faculty positions.

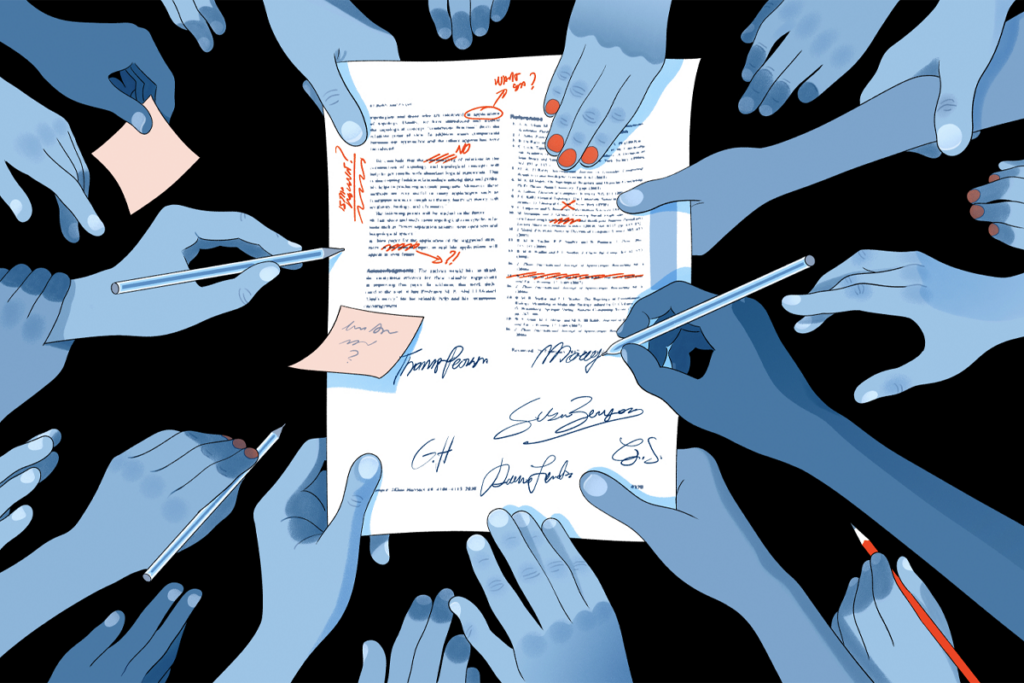

In this system, PIs get to retain, for years, an experienced researcher who can run experiments and publish but also write grants and mentor graduate students—all for about three-quarters of the salary of a staff scientist. This has been advantageous as science has become more labor intensive: Papers published before the mid-1970s had two authors, on average. Today, the average is six.

The tension between these forces is spilling out into the open. Social media is rife with postdocs describing their “exploitation,” from expectations of long hours to threats of lapsed visas for international postdocs who refuse to take on extra work. Postdocs have also become more forthcoming with their PIs. “If you contrast how people talked about this when I was starting my postdoc to now, it’s crazy,” says Jakob Voigts, a group leader at Janelia studying how animals learn from limited data. When Voigts was in training, senior peers told him to avoid mentioning industry, conceal if he had a romantic partner and otherwise hide aspects of his life that might make him appear “not serious about science,” thereby hurting his chances at a PI position. Now it’s “normal” for his postdocs to tell him “they might want to abandon the whole thing and go to industry,” he says. This meshes with findings of a study published last week, which found that about 41 percent of postdocs leave academia.

The COVID-19 pandemic seems to have made things worse. Social distancing made it harder to run experiments, share ideas with colleagues and get guidance from PIs. Half of postdocs surveyed in July 2020 said their level of job satisfaction had worsened that year, and nearly two-thirds said their career prospects had worsened, too. On top of that, the expectations around the postdoc experience had previously been passed down through a sort of cultural osmosis in the lab. But the pandemic and social distancing blocked that transmission, Voigts says, and “the whole expectation got completely reset.”

With in-person lab meetings and journal clubs on hiatus, discussions moved to social media, where postdocs used hashtags and threads on X (then Twitter) to commiserate about long hours and weekends without overtime pay. The pandemic “reframed a lot of people’s priorities,” says Ubadah Sabbagh, chief of staff at Arcadia Science and a former postdoc at MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. It forced people to pause and reflect on “how you’re investing your energy, your emotions, your thoughts in the world.”