Neuroscience Ph.D. programs adjust admissions in response to U.S. funding uncertainty

Some departments plan to shrink class sizes by 25 to 40 percent, and others may inadvertently accept more students than they can afford, according to the leaders of 21 top U.S. programs.

The Ph.D. application process crescendos during the first few months of every year: Prospective students visit schools, programs extend offers, and applicants decide which one to enroll in by 15 April. But this year, changes to the funding infrastructure of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) have disrupted that process.

Over the past month, President Trump’s administration has taken steps to stall grant reviews, freeze funding allocations and cut the “indirect cost” payments universities receive from federal grants. As a result of this uncertainty, neuroscience Ph.D. programs are scrambling to assess their own finances and determine how many students they can afford to admit this year—all while the admissions process continues apace.

The Transmitter reached out to senior leadership and others involved in 50 of the top neuroscience programs in the United States to ask how the shifting funding landscape has affected their admissions process; representatives from 21 programs responded.

The heads of nine programs said they are proceeding with the admissions process as usual and plan to admit their typical number of students or close to it: Harvard University, Duke University, Baylor College of Medicine, University of Chicago, University of Cincinnati, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dartmouth College, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and Ohio State University.

Another eight program leaders told The Transmitter they have reduced the number of students they plan to enroll in their neuroscience departments. For example, the University of California, Berkeley plans to decrease its class size by 20 percent; the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill biological and biomedical sciences program, which includes the neuroscience program, and Oregon Health & Science University reduced their class sizes by 25 percent; the University of Miami plans to drop from between 10 and 12 students to between 5 and 8; the University of Maryland, Baltimore aims to recruit a 40 percent smaller class than usual; and the Ph.D. program in neurobiology and behavior at the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine) expects to take 9 or 10 students this year instead of its usual 13 to 15. Brown University also plans to decrease the size of its neuroscience program by about half. The four other respondents described more complex situations, such as paused admissions or concerns about higher acceptance rates than normal.

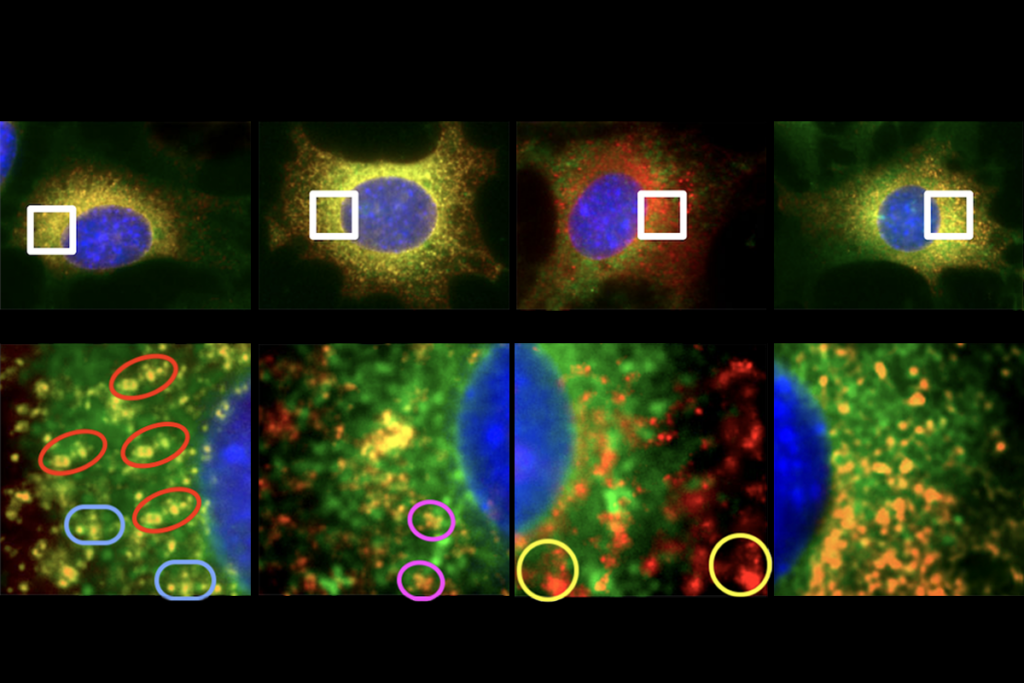

Currently, the most pressing reason to reduce class size is the ongoing threat to NIH and National Science Foundation grants rather than the potential cap on indirect costs, says Marcelo Wood, professor and chair of the neurobiology and behavior department at UC Irvine. “It’s one thing to support their salary, and it’s a totally different thing to be able to support the research that they do. The research is very expensive,” he says. “If you can’t support the research, no one’s going to make progress towards a Ph.D.” Programs also need well-funded faculty members willing to take students on, Richard Huganir, chair of the neuroscience department at Johns Hopkins University (JHU), and others say.

Huganir’s department has decided to reduce its typical class of 20 to 15 students, he says. (Nature reported last week that JHU’s cuts were not made in response to the current federal-funding situation. But JHU left the decision to the individual programs, Huganir says.)

The neuroscience department is trying to “admit as many as we can without being fiscally irresponsible,” Huganir says. “Everyone is being conservative because they don’t know what’s coming next.”

G

raduate programs typically extend offers to more students than they can accommodate, with the expectation that only a portion of the prospective students will accept. In light of the shrinking class sizes at many institutions, schools could see a larger proportion of students than usual who accept their offers of admission this year, which means programs could end up enrolling more students than they can afford, says Samuel Pleasure, director of the neuroscience program at the University of California, San Francisco. To avoid this potential issue, he says his program reduced the number of offers it made by 30 percent. A class larger than the program’s typical 15 to 18 students “would be a major stress on our resources in a time when we don’t know if our resources will be safe,” he says.The UC Irvine program switched from sending all offers out at once to a rolling admissions format to ensure they do not exceed their allotted spots, Wood says. Similarly, JHU created a waitlist to have more flexibility, Huganir says.

Northwestern University had already planned to admit a smaller-than-usual class this year, says Gregory Schwartz, director of the interdepartmental neuroscience program and professor of ophthalmology. The program typically enrolls 20 to 25 students each year; about one-third of the students who receive an admissions offer accept it, he says. But last year that figure rose to one-half—36 students—after a ratified union contract gave graduate students an increased stipend, he adds.

The program planned to admit 17 or 18 students this year to offset last year’s large class, Schwartz says. Admission offers went out to 35 students, based on the expectation that half of them would accept. Now that other programs are decreasing their class sizes, Schwartz says he is worried even more students will accept his department’s offers, which would create “lots of strain.”

The offers that have been sent out are a “binding contract” for funding, Schwartz says. The university covers the first six quarters of each student’s stipend; after that, each lab must fund its trainees, Schwartz says. “It’s all connected, ultimately, to NIH grants,” he says, and if the indirect cost cap is implemented, “the whole thing collapses.”

A

nd other programs are stuck in limbo or are further considering the best path forward. The neuroscience program at the University of Pittsburgh had already sent informal acceptance notifications to students in early February by the time the institution paused all Ph.D. admissions in the middle of the month, a university employee affiliated with the neuroscience program, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation, told The Transmitter. This pause meant that the program could not send formal admissions and funding offers. The pause has since been lifted, and the official offer letters should go out shortly, but an exact date has not been shared, the employee says.The program admits about 20 students each year, and there has not been any indication that there will be a reduction this year, the employee says, but “not knowing and being sure are two different things.”

The neuroscience graduate program at the University of California, Davis is still in the process of recruiting and interviewing students and has not decided how many offers to make, says program director Elva Diaz, who adds that she hasn’t grappled with such a calculation before. “It’s just very frustrating because we can’t base this [decision] on any data.”

The instability of this year’s admissions cycle could deter prospective researchers from pursuing graduate studies or drive them out of academia altogether, Wood says. “That’s what’s terrifying, because we will lose a whole generation of incredible researchers.”

Recommended reading

More than two dozen papers by neural tube researcher come under scrutiny

Static pay, shrinking prospects fuel neuroscience postdoc decline

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuroscientists reeling from past cuts advocate for more BRAIN Initiative funding

How to be a multidisciplinary neuroscientist